Orbán’s true reasons for opposing Ukraine’s EU accession revealed

At the end of last year, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán was in the spotlight again, after being the only EU leader to oppose starting Ukraine’s EU accession talks. Among the arguments put forward by Orbán were that Ukraine was too corrupt and that its accession would impose a huge financial burden on other member states.

But months earlier, in a closed meeting, he voiced very different concerns. They were rather related to fears about his own government’s geopolitical maneuvering. He said that Ukraine’s accession to the EU would change the balance of power in Europe and give the United States too much influence in the region.

This meeting took place last spring in the Hungarian Parliament. Orbán was speaking at what MPs called the “EU Grand Council,” a Hungarian parliamentary forum that must be convened before European Council summits. Here, the prime minister is usually briefing senior members of parliament, including several opposition MPs, on what to expect at the summit in Brussels in a few days’ time.

Help us tell the truth in Hungary. Become a supporter!

According to regular participants in the “EU Grand Council,” the atmosphere here is much calmer than in public parliamentary sessions, and Orbán often shares his more far-reaching visions. Direkt36 learned about the details of the 2023 spring meeting from sources with close knowledge of the details of the discussion. We asked Orbán’s press chief several questions to confirm what the prime minister said but have not received any answers.

US masterplan

Last year, the European Council summit took place on March 23, and it did not yet include the start of Ukraine’s accession to the EU on its official agenda. Orbán, however, did dive into the issue at this closed session of the Hungarian parliament held a few days earlier, on March 20.

According to sources familiar with the details of the meeting, the prime minister told the participants that, according to intelligence reports, the United States had promised Ukraine that EU accession talks with the war-torn country would start in 2023. “Zelensky will go into the presidential election campaign with the message that negotiations with Ukraine have begun,” Orbán said, suggesting that this would strengthen Zelensky’s domestic political position.

(Orbán did not mention it, but Ukraine’s integration process has a history. The country was granted candidate status in June 2022, after applying for membership just days after the Russian invasion began. At the beginning of 2023, leading Ukrainian politicians expected that the accession negotiations could start soon. Although EU leaders voted to open negotiations late last year, it now looks likely that Ukraine’s presidential elections will not take place in spring 2024 due to the war.)

However, Orbán said that things would not go so smoothly, referring to the need for unanimity to approve the start of accession negotiations and that the Hungarian government can impose its will in certain issues. The prime minister said they would insist that Ukraine restore the rights that the Hungarian minority enjoyed before 2015. Orbán also said that this was a position that was easy to represent in public, a principle similar to “white men eat with forks and knives” (a Hungarian saying which means that something is evident).

Orbán also added that the Hungarian government would accept no new Ukrainian proposals in the field of minority rights, as it is unpredictable how they would actually work in practice. (The reference to the pre-2015 situation in minority rights in Ukraine has been part of the Hungarian government’s communication for some time, and foreign minister Péter Szijjártó posted about it on Facebook a few days after the parliamentary council meeting.)

Orbán, however, indicated that while he believes Hungary can achieve some results, it would not be able to put up any substantial obstacles to Ukraine’s accession. He said that, despite his objections, Ukraine’s EU membership would be “pushed through relatively quickly.”

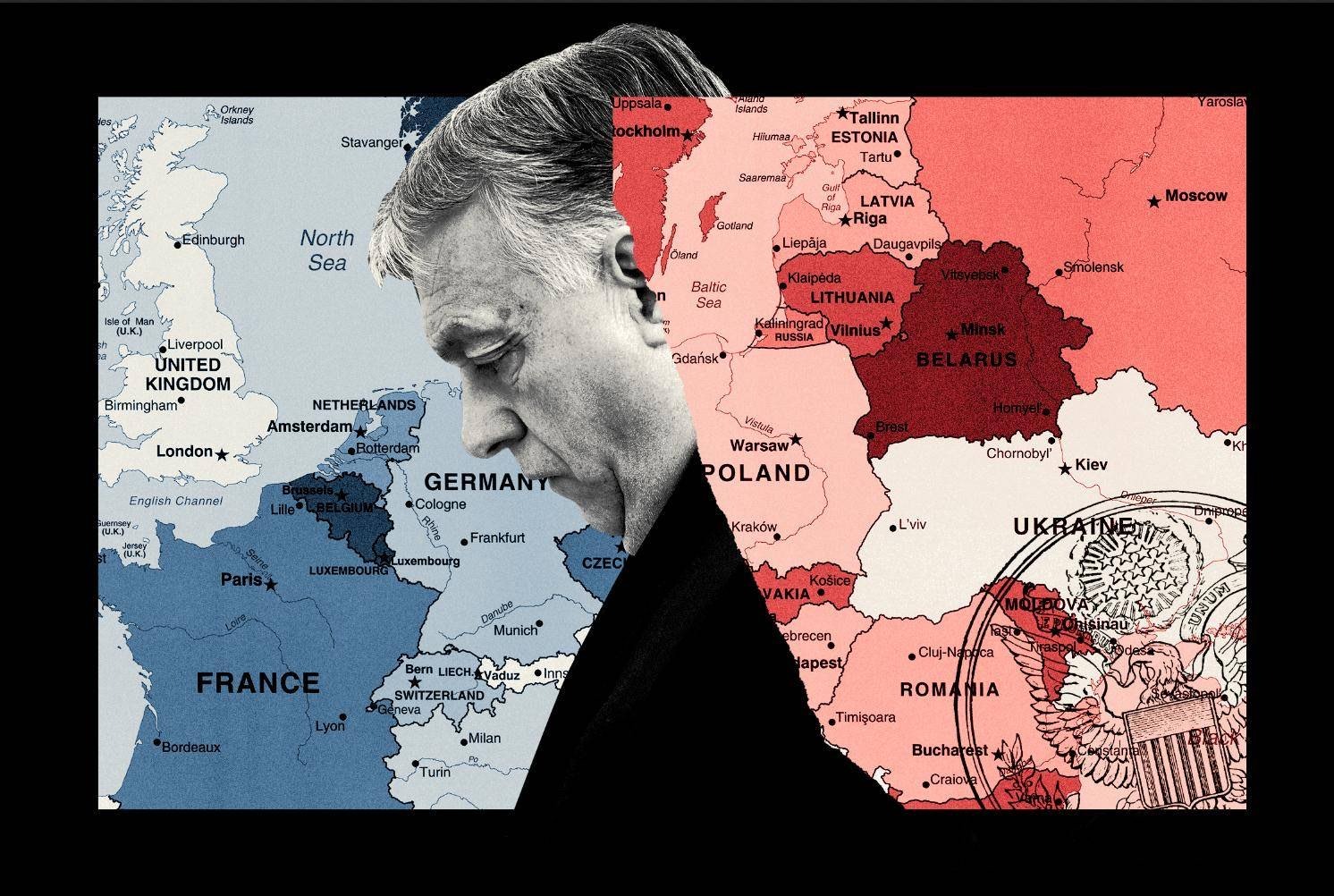

He then turned to the geopolitical risks he sees in Ukraine’s EU membership. Orbán said that Ukraine’s accession would create such a “center of power” within the EU which would be dominated by the United States, militarily, politically as well as economically. This north-central European zone would include, according to Orbán, the three Baltic states, Poland, Ukraine – which has been deprived of parts of its territory by Russia –, and, to a lesser extent, Romania (countries which, fearing Russia, maintain closer ties with the US).

According to the prime minister, the importance of this north-central European zone is also shown by the fact that the US is now deploying weapons only in Poland and Ukraine, instead of Western Europe. “We will see about Belarus, one or two colorful revolutions could still happen there,” Orbán said, referring to the series of protests that broke out in several post-Soviet countries earlier – and which the Russians say were supported by the US. According to Orbán, a possible Belarusian revolution would make this US-dominated European zone even larger.

The prime minister also went on to consider how large the population of this bloc would be. Orbán gave concrete figures, calculating that the population of the Baltic states, Poland, and Ukraine would exceed that of France so that this zone would be more influential than France. Orbán also said that he had shared this theory with Emmanuel Macron, but it was “not quite clear” to the French president “how should it all be added up” (meaning the population of these countries).

Orbán and Macron – Source: Orbán/Facebook

In this 2023 closed session, Orbán also spoke about the figures he had shared with Macron. In the case of Ukraine’s future population, he put it at 20 million, suggesting that the population of the country, which was 32 million before the war, would decrease by that much because of the Russian invasion (Orbán’s own calculation slightly underestimated the French population and overestimated the number of Poles, because, if official figures are taken into account, Poland, with 38 million, the Baltic states, with 6.1 million, and Ukraine, with 20 million, together do not exceed France’s population of 68 million).

Orbán claimed that this bloc would be significant economically too. He expected that this would be due, among other things, to the inflow of US investments and resources for the reconstruction of Ukraine. All this, he said, will lead to “this new power center” being “economically stronger than Germany.” Orbán believed that this strategy, which he calls “American-Polish” strategy, would change the balance of power within the EU and reduce the influence of the currently dominant German-French axis.

“We had an offer to the good French and Germans, who did not accept it,” Orbán said of his earlier attempts to maintain the status quo within the EU. To this end, he proposed that the Franco-German axis should be complemented by the Visegrád Four (i.e. the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia), which, Orbán argued, could have consolidated the EU’s eastern half, had they been more closely involved in EU decision-making. According to Orbán, his proposal did not get support because Germany saw the Visegrád group as a rival, and tried to break it up instead. According to the prime minister’s logic, this is why, among other things, rule of law proceedings were launched against Poland. Orbán concluded that the Germans and the French have caused trouble for themselves, and instead of “strengthening Europe’s strategic autonomy” they have offered Central Europe up for grabs to the Americans.

Orbán’s speech also revealed that this shift of power bothers him because it interferes with his own strategic vision. The prime minister said that he believes that the center of gravity of the world economy is shifting from the West to Asia, including China, mainly for demographic reasons. Orbán said he did not think it was right that “the Americans are reacting to this by splitting the world economy in two.” He said that in this process, we should not choose between the Western and Eastern hemispheres, but instead “we should be able to develop all kinds of relations with everyone in accordance with our own interests.” He said that Hungary should take advantage of the benefits of both Western and Eastern relations in the next decade.

Orbán listed a number of Eastern countries that he considered important for the implementation of this “Hungarian strategy.” He mentioned China, for example. He said that the Hungarian government also wants to deepen relations with India, but that they have not yet found a way to do so. He also added that, after the end of the war, “some kind of relationship with the Russians will have to be established within the new security framework.”

The prime minister has already shared some of these ideas publicly. For example, he said similar things in a speech to the Hungarian Chamber of Commerce and Industry a few days before this parliamentary meeting in spring 2023. Here, however, Orbán presented his theory much more briefly, and his comments on the role of the United States were limited, so they received less attention.

Money would flow into US pockets

The Hungarian government started to criticize launching Ukraine’s EU accession talks more vehemently after the European Commission made an official proposal at the beginning of November 2023. The Hungarian government reacted to the announcement by following the agenda outlined by Orbán, referring to minority rights as an obstacle. Later that day, Péter Szijjártó said in a Facebook video that Ukraine was not fit for EU membership. “We Hungarians continue to expect Ukraine to return to the Hungarian community in Transcarpathia all the rights they possessed in 2015,” he said.

In the meantime, however, Ukraine also took action. Early December last year, several laws necessary for the start of accession were adopted, including one on minority rights. The new law made it possible to teach in official EU languages, including Hungarian, in Ukrainian schools. In response, the Hungarian government said that it would evaluate the new law, but that it was still a long way from the restoration of the pre-2015 minority rights.

Orbán and leaders of EU – Source: Orbán/Facebook

In the period that followed, references to minority rights were scaled back in government communication. Orbán also started to use different arguments. One of them was that Ukraine was not ready for accession. “Ukraine is known as one of the most corrupt countries in the world. This is a joke!” he told the French weekly Le Point last December.

Among the prime minister’s counterarguments was that huge amounts of money would be spent on the reconstruction of Ukraine. For example, he told the Hungarian parliament on December 13 last year that Ukraine would receive ten times more in EU agricultural subsidies than Hungary was entitled to. “Moreover, a substantial part of this money would actually go into the pockets of the Americans, who have bought into the Ukrainian agricultural sector up to their necks,” he said. He added that US Secretary of State Antony Blinken recently said that 90 percent of the money the US sends to Ukraine comes back to the US and helps create jobs and growth on US soil.

In a letter to European Council President Charles Michel in early December last year, Orbán suggested that the issue of Ukraine’s accession should be removed from the agenda of the next European Council. The European Commission’s proposal needed a unanimous decision by the leaders of the member states at the summit on December 14-15.

Orbán also told Michel that he did not agree with the €50 billion in financial support for Ukraine planned until 2027. The prime minister’s previous statements showed that he was opposed to this because he was against the EU taking a loan for it. Moreover, he felt that it was a waste of money because the Ukrainian army had not delivered the expected military results.

Orbán’s threat of a veto drew a lot of attention at the December summit. On the first day of the meeting, the opening of accession negotiations was approved. This was achieved by Orbán leaving the room at the moment of the vote, as suggested by German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, in a pre-arranged way. The Hungarian government said afterwards that unanimity would be needed in many cases during the long accession negotiations anyway, so there would be still plenty of opportunity for them to veto.

The next day, however, Orbán vetoed the decision on the financial support for Ukraine, which was more urgent than starting the EU accession negotiations. It later emerged that Orbán was open to some kind of a compromise on this issue too. In early January 2024, Politico reported that the Hungarian government had suggested that the veto would be lifted if funding for Ukraine was reviewed on a yearly basis. This would mean that the Hungarian government would have the opportunity to blackmail the EU with a veto every year.

Illustration: Szarvas / Telex