Company of Orbán’s father found in yet another huge EU-financed project

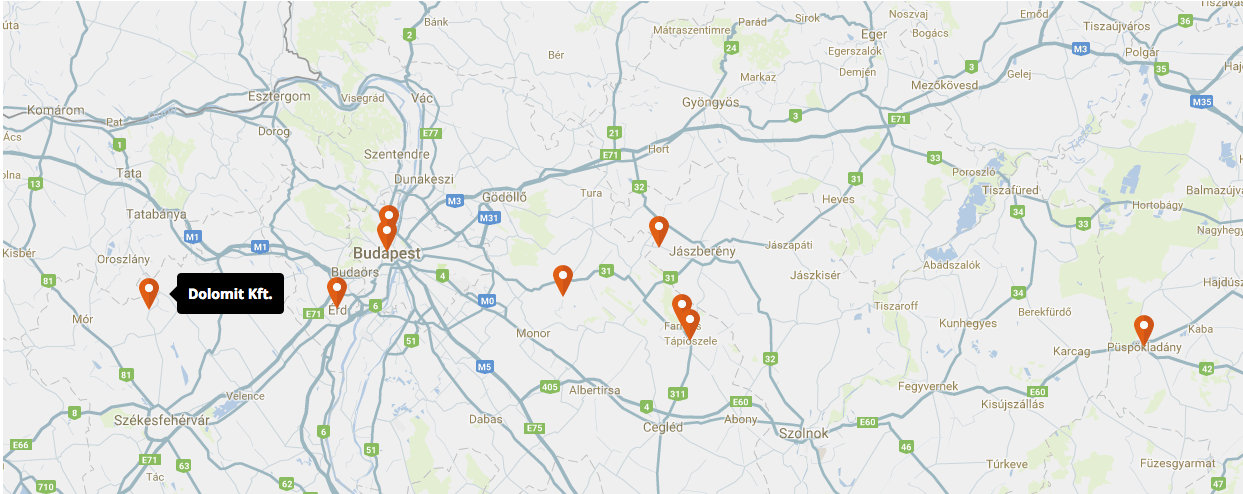

The spring of 2014 was busy at the company of the Hungarian PM’s father, Győző Orbán. Shortly after delivering hundreds of manhole elements for the construction of the sewerage system in Érd – a city near the Hungarian capital of Budapest – Dolomit Ltd. jumped into two new projects. From the company’s industrial site in Gánt, trucks started to deliver concrete elements for the capital’s sewerage construction, while others, loaded with similar products, set off towards smaller towns in Pest county.

In our previous article, we have revealed that the outstanding performance of the businesses of the prime minister’s family was helped by their involvement in state projects, such as sewerage constructions in Érd and Budapest. These projects were funded by the European Union, a frequent target of Mr. Orbán’s government. Direkt36 has obtained new documents, which prove that the firm of the PM’s father participated in yet another EU-funded investment, namely the sewerage system construction project in the Tápiómente Region. The project affected 20 towns in the region, and had a budget of almost 25 billion forints (81 million euros).

We can only do this work if we have supporters.

Become a supporting member now!

Similarly to the projects presented in our previous article, it is difficult to get a clear picture about the scope of the Orbán-company’s involvement in the Tápiómente project. Dolomit Ltd., majority-owned by Győző Orbán, and other businesses involved in the project did not answer our questions. At the same time, the project documents of the Tápiómente investment revealed that – besides Közgép Ltd., Duna Aszfalt Ltd. and the firm of the PM’s friend Lőrinc Mészáros, already mentioned in our previous article – various companies regularly involved in public investments also worked together with the Orbán-company. Euroaszfalt Ltd., A-Híd Ltd. and Penta Ltd. ordered building materials from Dolomit Ltd. although they are said to be more expensive than the competitors’ products (some sources added that Dolomit Ltd.’s products are of better quality).

Until recently, 18 towns in the Tápiómente region, an hour’s drive from the capital, did not have a sewerage system, while in two other towns it was only partly built. In early 2010, the municipalities received 24.8 billion forints (80.32 million euros) of support for the sewerage system development, 84% of the funds paid by the European Union. Inhabitants also had to pay a contribution to the investment, which was 265.000 forints (860 euros) per property, paid in one or two instalments.

When looking into sewerage system projects, it is easy to find out which companies won the public tender, as their name is published online. However, the identity of the companies that supply building materials for the project is not disclosed in the public databases. In the case of the Tápiómente investment, only after a month-long discussion with the authorities and a complex authorization process were we able to find information about the suppliers by looking through thousands of pages of archive project documents, piled up in big boxes and folders in an abandoned storage room.

According to dozens of delivery notes we found, during 2013 and 2014 Dolomit Ltd. supplied hundreds of tonnes of different types of manhole elements for the sewerage construction of three towns of the Tápiómente Region, Úri, Jászfelsőszentgyörgy and Farmos. Other documents also make it clear that Dolomit Ltd.’s products were used for the sewerage construction in another town, Tápiószele.

During these projects, the clients of Dolomit Ltd. were construction companies that had also won many other high-value public contracts in recent years.

For the construction of the sewerage system in Úri and Jászfelsőszentgyörgy, it was Euroaszfalt Ltd. that ordered manhole elements from the Orbán-company. As a member of a consortium, Euroaszfalt won a public tender for the sewerage system construction in 11 towns of the Tápiómente region. In five additional towns, the company participated in the project as a member of another consortium called Tápiómenti CME. The other two members of this consortium were the company of Mészáros Lőrinc, Viktor Orbán’s friend whose wealth increased massively over recent years and Colas Alterra Zrt., which belongs to the France-based Colas group. Euroaszfalt Ltd. lists several other public projects among its work references on its website, including railway and motorway constructions, besides wastewater projects.

[gview file=”//www.direkt36.hu/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/szállítólevelek.pdf”]

Another buyer of Dolomit’s products was A-Híd Ltd., which ordered manhole elements for the sewerage system construction in the village of Farmos. After our article was published, A-Híd answered some our questions. The company said that they had chosen the products of Dolomit Ltd. because “with regards to technical parameters, they were the most suitable products for the procurement’s requisites.” They added that Dolomit Ltd.’s products “differ in terms of material, wall thickness and production technology” from the ones of other companies that produce concrete elements.

A-híd Ltd. also won several other public tenders. As a member of a consortium, for example, it participated in the sewerage system project in Budapest and also in the construction of the M4 motorway. In the Tápiómente Region, it worked on the sewerage system project in four settlements, in consortium with construction companies Strabag and Penta Ltd. A-híd Ltd. told Direkt36 that apart from the sewerage system construction in Farmos, they did not order products from Dolomit Ltd. for other public projects.

Penta Ltd. used Dolomit Ltd.’s manhole elements for the sewerage construction in Tápiószele. This was not the only case, however, when the two companies cooperated. Concrete elements manufactured by the Orbán company also appeared at the site of the sewerage system constructions on Budapest’s Margaret Island, a public project won by Penta Ltd. as a member of a consortium.

Do you have an important story?

Share it with us on secure channels!

The revenue of Dolomit Ltd. almost doubled between 2012 and 2015, while its after-tax profit has more than tripled. It is hard to estimate to what extent the company’s involvement in the Tápiómente project contributed to this growth, due to various reasons. To begin with, winners of public tenders do not always disclose suppliers’ delivery notes as part of the project documents. Even if they do, these notes only contain information about the type of the products supplied, but not their price. The municipalities and project management companies do not collect information about the payments made to suppliers. This information might be held by the winners of the public tenders, contracted by the state. However, neither the firms involved in the project, nor Győző Orbán’s company answered our questions related to these projects.

For the Hungarian company data we used the services of Opten and Céginfo.