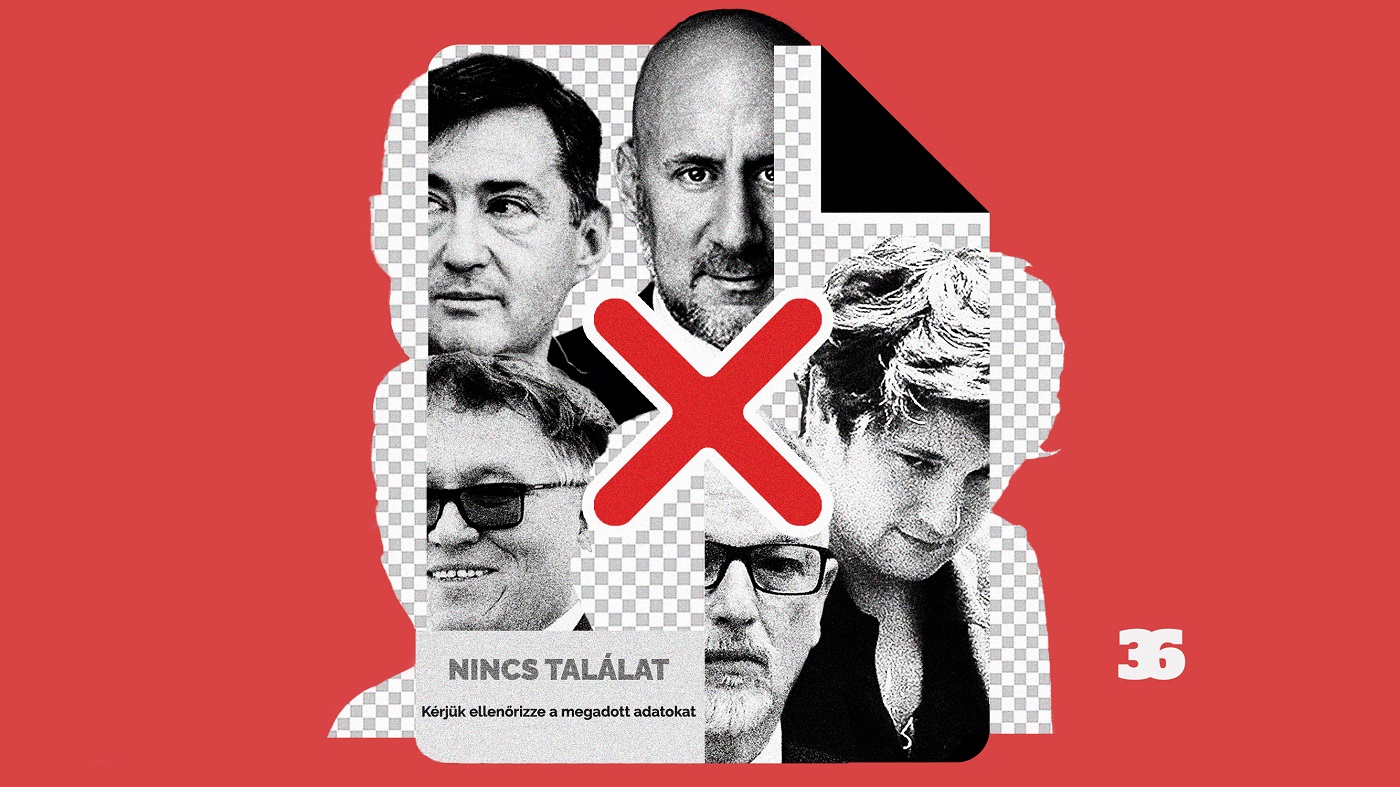

The owners of private equity funds, which hide huge wealth, have been removed from the state register, after Direkt36 published an article about them

In January this year, Direkt36 was able to identify a number of pro-government businessmen behind private equity funds that were hiding huge fortunes, using an official database managed by the tax authority. This form of investment, which has become increasingly popular among the wealthy in recent years, offers low taxes and anonymity – similar to offshore companies – and as a result hundreds of billions of forints have been channeled into newly established private equity funds.

A rare glimpse into this hidden world was provided by the NAV’s so-called beneficial ownership database, which has been operational since 2021 and included the names of dozens of private equity funds’ largest investors. Among them were a number of well-known billionaires close to the government, such as István Száraz, László Szíjj, Lőrinc Mészáros, Zsolt Hernádi or Gellért Jászai. As Direkt36 wrote, this could have happened because the database was recent and the rules governing it were complicated, so it was not always clear what data should be included.

Since the publication of this article, however, private equity funds have disappeared from the database completely. Even those that were previously included have been removed.

At the beginning of the year, the search term “private equity fund” had 37 meaningful hits in the NAV database, but this had been zeroed out by July. However, in the six months between the two searches, the number of private equity funds continued to grow rapidly: while in January the Hungarian National Bank (MNB) had 119 private equity funds registered, in the second half of July its search engine now lists 182.

In the meantime, the relevant legislation has not changed and no new guidelines have been published. The data on private equity funds have simply been deleted. However, no one takes responsibility for this. The tax authority that operates and supervises the database replied to Direkt36 in a one-and-a-half-line reply that they do not supervise the contents of the database:

‘The beneficial ownership database shows the data provided by the account holders monthly. This data is published by NAV without any changes.’

So the data is submitted by the bank that manages the account of the private equity fund. We contacted the Banking Association, which brings together domestic financial institutions, to ask whether the banks concerned had indeed removed the private equity funds from the database, but they did not respond.

The Hungarian National Bank (MNB) also does not monitor what is included in the beneficial ownership database, although it has previously issued guidance on how to identify the true owners of companies and other more complex forms of business. According to them, the supervisory body – responsible for combating money laundering in Hungary – is NAV, and the legislator, the Ministry of Economic Development (GFM), should answer questions. But GFM has not responded to our inquiries.

We have also contacted 8 private equity fund management companies, which together manage more than 20 private equity funds, about the erasion of the data. Many of their funds were previously found in the NAV database.

At the end, four of them answered our questions. Opus Global Investment Fund Management Ltd., related to Lőrinc Mészáros, said that neither the deletion nor the modification of the data had been initiated by them. The IKON Fund Management Company, linked to Gellért Jászai, also wrote that although they had previously initiated the process of clarifying the data on their private equity funds in the NAV system, they had not taken steps to delete them. According to the Central European Venture and Private Equity Fund Management Company, managed by the son-in-law of PM Vitkor Orbán, István Tiborcz’s business partner and friend Bálint Szécsényi, only NAV is competent in the matter.

József Tamás Kertész, known as the lawyer who handles pro-government billionaire Lőrinc Mészáros’ business affairs, and also the chairman of the board of Primefund Investment Fund Management, did not give a clear answer as to whether the deletion of the data was initiated.

‘My position does not allow me to give an answer, I cannot answer due to the rules of my profession,’

said Kertész, who claimed that the law prescribing the beneficial ownership database does not mention private equity funds, suggesting that he does not believe they should be included in the system.

This is indeed the case, private equity funds are not explicitly mentioned in the relevant law or in other anti-money laundering legislation, nor are they mentioned in MNB’s previous guidance. Nor, however, does any rule state that they are not subject to these transparency rules.

The beneficial ownership registers were created through an EU initiative as part of the fight against money laundering. The aim was to identify the beneficial owners of European businesses and make them recognizable with certain restrictions. Gábor Szabó, an expert who works as a compliance manager for fund managers in Luxembourg and the UK, says it may be a failure of the Hungarian legislator not to clarify what to do with private equity funds, but they are clearly covered by EU anti-money laundering guidelines.

Szabó said that other countries take the fight against money laundering much more seriously than Hungary. ‘The fact that there are private equity funds that are not or inaccurately listed in the beneficial ownership database, or that only their managers are named, should in itself be sanctioned. Moreover, this should be monitored by a range of actors from the bank to the fund manager,’ he said. He claims the rule was clear, all persons with a minimum 25 per cent interest and decision-makers should be considered beneficial owners. ‘It is up to the authority to enforce this,’ he added.

Why are private equity funds important in Hungary?

The special rules applying for private equity funds offer investors the possibility to hide huge fortunes. While in the case of traditional companies anyone can obtain official information about their ownership and finances with a few minutes of online research, private equity funds are different.

It is a form of investment in which a closed circle of investors can put their money and grow their wealth without being subject to company disclosure rules. The money is held by a fund manager company on behalf of the investors. The ownership of the fund manager is public, but it is not possible to find out whose money is in the private equity fund they manage.

Private equity funds exist in many countries around the world, primarily for investment purposes. In Hungary, however, a few years ago, the business elite close to the government saw the potential of their secrecy and started using them like offshore companies are used elsewhere: to increase their wealth in complete secrecy.

As a result, private equity funds have multiplied in Hungary, and hundreds of billions of HUF worth of wealth have been transferred to them. A series of fund managers linked to billionaires close to the government have built ever larger portfolios. Money has been invested in almost every sector of the economy. Private equity funds own, for example, the 35-year-old Hungarian motorway concession, hotel chains, dozens of Budapest’s luxurious palaces, restaurants, banks, industrial companies, waste treatment plants and many others. Valuable state-owned properties and companies have also been transferred to private equity funds, ultimately enriching the wealth of unknown individuals.

This is why it was significant that Direkt36 found in January the ultimate beneficial owners of about a fifth of the private equity funds operating at that time, 26 in total, in the NAV database, and 17 of them were clearly pro-government, but another five were easily linked to pro-government business circles. It was the first time that an official database had included the country’s well-known billionaires, from Lőrinc Mészáros to István Száraz. In several cases, this surprised even the managers of the private equity funds themselves.

The data revealed, among other things, that István Száraz, a friend of the central bank president’s son Ádám Matolcsy, was the ultimate owner of almost 11% of the Hungarian superbank Magyar Bankholding, which was created this year. Two private equity funds were also held in January by a property trader from Pécs called Áron Hornung, who also did business with billionaire investor Dániel Jellinek and has several links to István Tiborcz’s business partner Endre Hamar. The private equity fund that won the Hungarian motorway concession for 35 years, in a consortium with six other private equity funds, was owned by billionaire László Szíjj, a business associate of Lőrinc Mészáros.

This information has disappeared from the NAV register since the publication of our article in January. And the missing private equity funds and the new private equity funds created in the meantime have never been included in the search engine.

Illustration by Máté Fillér/Telex