Prominent business allies of Viktor Orbán’s government had secret offshore businesses, Pandora Papers reveal

At a session late at night in May 2016, the members of Hungary’s parliament were debating what actions could be taken against offshore companies.

The debate was triggered by the Panama Papers, a global investigation that weeks earlier had revealed in unprecedented detail how the world’s leading politicians, powerful businessmen, celebrities, and criminals were hiding their wealth in various offshore jurisdictions.

Members from the ruling Fidesz party used particularly harsh words and tried to paint the situation as if the problem only affected the leftist opposition. “When the current government took office in 2010, the offshore business flourished in Hungary. (…) So far, we have not been able to count on the opposition and currently we cannot count on it either in the fight against offshore. This is because the opposition is still full of offshore issues to this day,” said Csaba Dömötör, a state secretary in the Prime Minister’s Office headed by Antal Rogán, one of Fidesz’ most powerful politicians.

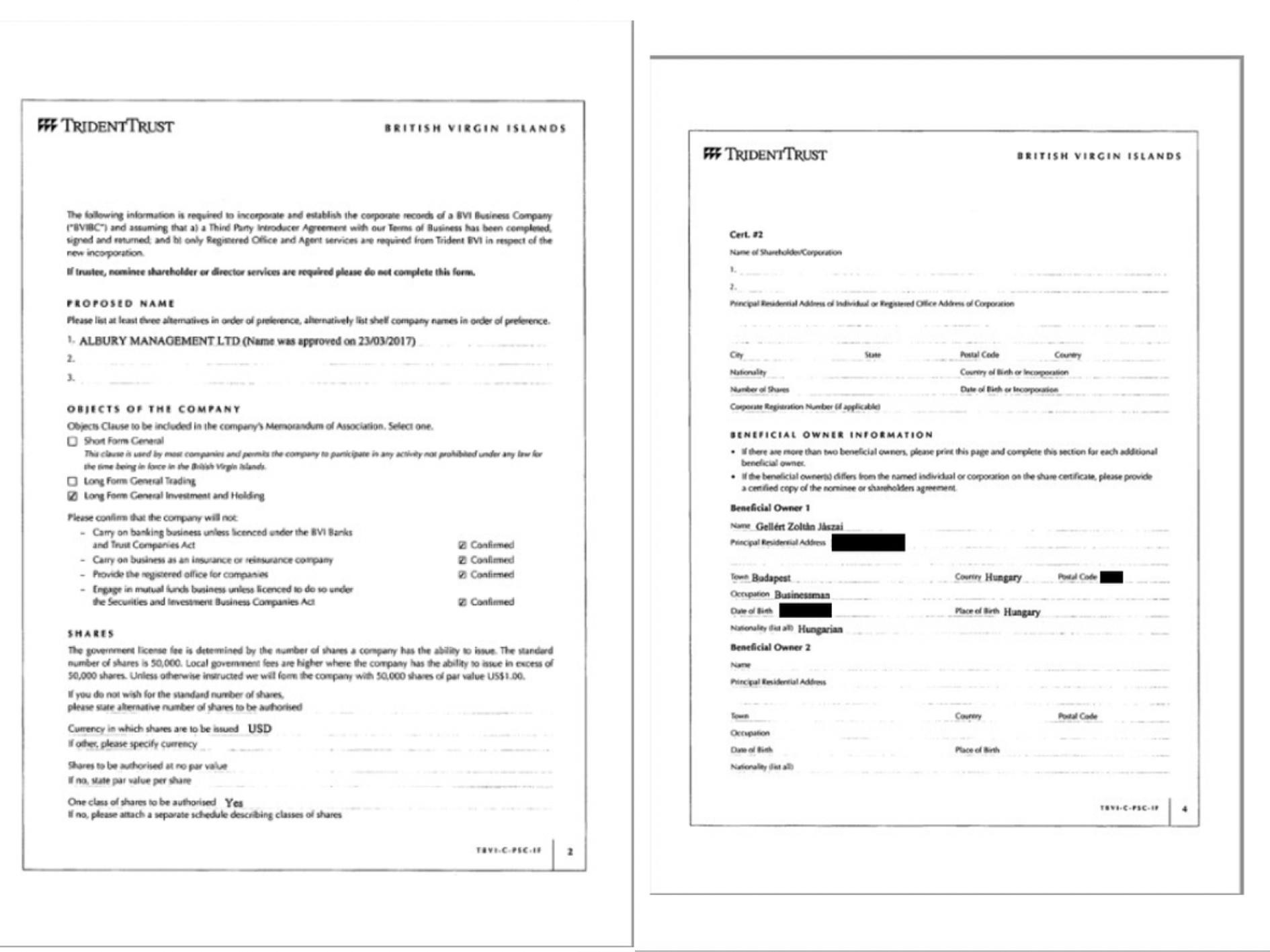

While Dömötör detailed the government’s anti-offshore measures, eight thousand kilometers away, a company providing offshore services in the British Virgin Islands has just put the finishing touches on an offshore deal of Balázs Kertész, a powerful lawyer and former Fidesz politician who is known for his close ties to Antal Rogán.

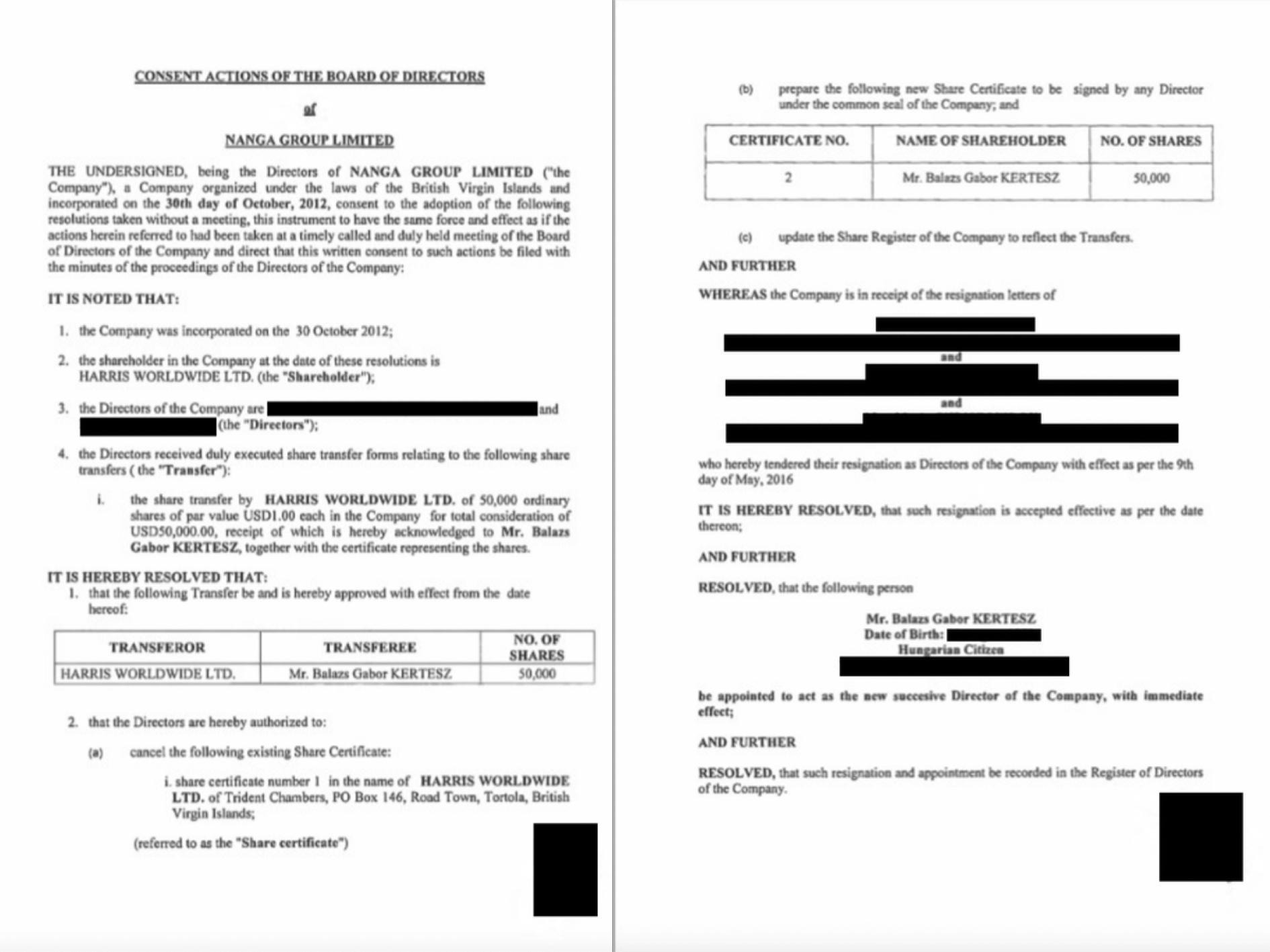

Balázs Kertész bought all the shares of Nanga Group Ltd. on May 9, 2016 for 50,000 USD and he was also appointed as the company’s sole director at the same time. The British Virgin Islands offshore service company performed the related administrative tasks in May, and then mailed a bill of 821 USD to Kertész on June 2. The address was Kertész’ office in Aulich Street near the Hungarian Parliament.

The records of this deal is part of a new gigantic offshore leak known as the Pandora Papers. The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists obtained the trove of 11.9 million confidential files and led a team of more than 600 journalists from 150 news outlets that spent two years sifting through them, tracking down sources and digging into court files and other public records from dozens of countries. The only Hungarian partner in the investigation is Direkt36.

The leaked data reveals that, in addition to Kertész, other prominent pro-government business figures have had secret offshore businesses.

- Gellért Jászai, currently the head of the IT company 4iG, who for years was a top manager in the business empire of Lőrinc Mészáros, a close friend of Viktor Orbán

- Zsolt Nyerges, an old friend of the Orbán family, who was a close aide of Lajos Simicska, the oligarch who helped Viktor Orbán build his political career

- László Horváth, an entrepreneur with ties to the government, Honorary Consul of Kazakhstan

The secret documents expose offshore dealings of the King of Jordan, the presidents of Ukraine, Kenya and Ecuador, the prime minister of the Czech Republic and former British Prime Minister Tony Blair. The files also detail financial activities of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s “unofficial minister of propaganda” and more than 130 billionaires from Russia, India, the United States, Mexico and other nations. For more details about the international findings of the global investigation, read ICIJ’s story.

Offshore companies, which are often registered in exotic countries, are used in general for two purposes. One of them is for minimizing the tax burden on income that a company or a person makes in other countries. Since the ownership data of these entities are in most cases very hard to access, these companies are also used for hiding assets or conducting shady businesses. It is because of these two characteristics that – even though owning or using offshore companies is legal – there have been major international efforts to crack down on their use.

A well-connected lawyer’s secret company

When in May 2016 Balázs Kertész bought his British Virgin Islands company, he still had a relatively low profile in Hungary.

The wider public learned his name from an investigative story that news site Index published about him six months later. According to the article, Kertész was the right-hand man of Antal Rogán when he was the mayor of Downtown Budapest. The story revealed, for example, that the company of Kertész’ wife was entrusted with the utilization of a patent registered to Rogán. And the law firm of Kertész’ university classmate Kristóf Kosik was one of the big beneficiaries of the controversial residence bond business that was initiated by Rogán.

Kertész, who himself had been a representative of Fidesz in the Budapest downtown council, also has direct ties to the Hungarian government. He has served on the board of the Hungarian Hydrocarbon Stockpiling Association at the request of the government. The state organization’s responsibility is to store and organize Hungary’s strategic oil and gas reserves.

Currently, Kertész has private companies dealing with consultancy and asset management. Last year, he moved these firms to a villa on the top of Gellért Hill, one of Budapest’s most elegant neighborhoods, but his official address is in a luxury apartment in the Swiss town of Zug.

The leaked documents related to the acquisition of Nanga Group Ltd. include a copy of Kertész’ Hungarian passport and his Swiss residence permit. The company was originally founded in 2012 and was owned by Harris Worldwide Ltd., a company registered at the address of an offshore service provider and a shareholder in many other British Virgin Islands companies. Nanga Group Ltd. was acquired by Kertész in 2016.

No information is available as to exactly what Nanga Group has been doing and what assets it has, nor is it known whether it is still owned by Kertész. We contacted Kertész by email and left a letter in the mailbox of his companies’ headquarters in Gellért Hill, but he did not respond to these inquiries.

Swiss bank account and three offshore companies

More detailed information can be found in the leaked documents about the secret dealings of another pro-government businessman, Gellért Jászai, who, like Kertész, also chose the British Virgin Islands (BVI) as the location of his offshore businesses.

Jászai was active in the fields of real estate and investments in the early 2000s. Later, he became a top manager in the business empire of Lőrinc Mészáros, a long-time ally of Viktor Orbán and one of Hungary’s richest businessmen. In 2015, Jászai became the chairman and CEO of Konzum, a listed company, in which Lőrinc Mészáros also bought shares in February 2017.

During this period, in February and March 2017, three companies were set up on the British Virgin Islands, which, according to emails and other documents leaked from an offshore service provider, were ultimately owned by Gellért Jászai.

According to documents connected to the companies’ registration, the purpose of the companies was, among others, to own bank accounts with a Swiss bank, VP Bank Schweiz. This is a Swiss subsidiary of Liechtenstein’s VP Bank, which has been operating since 1988. “With our offices situated near Paradeplatz on Zurich’s Talstrasse we are located at the heart of the Swiss banking scene,” the bank’s website states. When asked by Direkt36, Jászai’s IT company 4iG said that only one of the three offshore companies owned an account with VP Bank, and there were “no assets or cash flow” on this account either.

The leaked documents – submitted to an offshore provider before the establishment of the companies – also describe the assets that would be held by the companies:

- Albury Management Ltd. – approximately 10 million CHF

- Crompton Finance Ltd. – approximately 10 million CHF

- Burt Investment Ltd. – approximately 5 million CHF

According to the leaked documents, these assets not only include bankable assets but also shares held in Hungarian and Swiss companies. However, we did not find any traces of such subsidiaries in company databases. We asked Jászai to list the businesses owned by the BVI companies, but 4iG did not answer any questions related to the companies’ activities.

According to Virgin Island’s Official Gazette, the voluntary liquidation of all three companies commenced in July 2020. This happened ten days after Lőrinc Mészáros had sold his shares in the Hungarian company 4iG, which came under Jászai’s control. We asked Jászai if these two events had anything to do with each other, but according to 4iG’s response, at the time, he was no longer connected to the BVI companies. According to 4iG, Jászai has had “nothing to do with any of the listed companies since July 2017.” They added that Jászai “has no offshore interests and no hidden assets.”

We asked Jászai what the reason was for leaving the companies just a couple of months after their foundation, and we also asked who bought the companies from him. However, 4iG refused to answer, saying that these questions are related to “private and business secrets.”

The British Virgin Islands before 2010

Other businessmen close to the current Hungarian government already had offshore interests in the British Virgin Islands before Fidesz came to power in 2010.

- According to one document, Zsolt Nyerges was the director of Pannone Management Limited, a company registered in the BVI. Nyerges, a lawyer from Szolnok, became an important player in the economic empire close to Fidesz as a friend of the Orbán family. He worked together with Lajos Simicska, who, for years was one of the closest allies of Orbán but lost his power after a fallout with the PM in 2015. The leaked document is from 2009, and although the document does not reveal details about the company’s activities, it is the first sign that Simicska’s circle also used offshore companies. Nyerges told Direkt36 that he never comments on business issues. According to the leaked documents, Pannone Management was dissolved in 2011.

- László Horváth, a businessman close to government and honorary consul of Kazakhstan had an e-mail correspondence with an offshore provider – through a lawyer – in connection with a BVI company called L.A.C. International Ltd. “László Horváth used to be the director of L.A.C. International 2004 until its dissolution. The activities of the company were of consulting nature, it did not carry out economic activities. Unfortunately, there are no reports available for the period beyond the limitation period that would allow us to provide authentic information about the company’s financial and economic situation,” the Hungarian company of Horváth, L.A.C. Holding Zrt. wrote to Direkt36. According to the leaked documents, the BVI company became struck off of the BVI Register of companies in 2010 for failure to pay the 2009 government license fees.

The highest achievable degree of discretion

In the international market, many companies specialize in registering or buying offshore companies in various exotic countries, and they also manage those companies for the relevant fees. Although discretion is paramount in this industry, data about the activities of such offshore service providers have been leaked several times in recent years.

While the Panama Papers published in 2016 contained the internal documents of only one service provider, the Panama-based law firm Mossack Fonseca, the Pandora Papers contain data from a total of 14 offshore service providers.

The leaked documents make it clear that the offshore world is not only run by companies and lawyers with dubious backgrounds operating in remote and exotic island, but, in fact, this system is part of the international financial system. Offshore service providers work together with large banks and law firms in financial centers around the world.

According to information coming from the circle of one of the Hungarian businessmen who appeared in the data, it was his Swiss bank that recommended them a service provider that could set up offshore companies.

The offshore provider called Trident Trust also works closely with major financial players. Trident proved to be popular among Hungarian businessmen close to the government as well, as Balázs Kertész, Gellért Jászai, Zsolt Nyerges, and László Horváth also used the services of this company.

“Trident Trust is a relatively large player,” explained a Hungarian source who has been working in the offshore services industry but asked not to be named. The source added that, like many other service providers, Trident had an Anglo-Saxon background. In the leaked materials, the company itself writes that its first offices were established in the Channel Islands back in the late 1970s and then expanded to the Caribbean archipelago. Today, they have more than 900 employees and are present in Asia, Africa and the Americas.

“Included in our client base are many of the world’s largest banks and Fortune 500 companies as well as high net worth individuals and their family structures” – Trident writes in one of the leaked documents. Trident did not respond to Direkt36’s questions about its clients close to the Hungarian government but sent a brief statement through a London-based crisis management consulting firm, which states that “each of Trident’s trust and corporate services businesses is regulated in the jurisdiction in which it operates, and is fully committed to compliance with all applicable regulations. Trident routinely cooperates with any competent authority which requests information. Trident does not discuss its clients with the media.”

In the Caribbean companies of Kertész and Jászai, one of the former executives of Trident also appeared as a director: Irène Spoerry, a Swiss national who used to be managing director of Trident Trust Group for 25 years. (In Kertész’s company, Spoerry was a director before Kertész’s arrival, while in Jászai’s companies, Spoerry was appointed as one of the directors when the companies were established.)

Besides Trident, a Cypriot company called Stratus Associates Limited, currently managed by Spoerry, also took part in managing Jászai’s offshore affairs. Stratus advertises itself on its website by stating that “Stratus Group ensures at all times the highest achievable degree of security and discretion. Clients are accepted by introduction only. (…) Risks are either contained or not incurred.”

Spoerry wrote to Direkt36 that she “gladly would reply to any and all questions in connection with the companies” if they receive a court order based on a valid request for legal assistance. However, in the absence of that, she refused to provide details about the companies. She only confirmed that she used to be a director of Nanga Group, and, according to her e-mail, in the three other companies in which Jászai was named as beneficial owner, they resigned as directors in 2019.

For Hungarian company data, we used the services of Opten.

Illustration: szarvas / Telex