They try to hide it, but the involvement of Orbán’s father in huge railway construction project is revealed

For a couple of days, it seemed that official sources would tell Direkt36 who supplies building materials for one of the biggest ongoing construction projects in Hungary. However, a subtle reference to the Prime Minister’s family was enough to shut down the free flow of information.

The inquiry concerned a huge railway reconstruction project on the Southern side of “Hungary’s sea,” the Lake Balaton. The HUF 72 billion (€232 million) project is mainly financed by funds of the European Union, a frequent target of Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s attacks.

At the site of the reconstruction, several workers said that some of the building materials used for the project come from a mining company, whose majority shareholder is the PM’s father Győző Orbán. When we asked the main contractor of the construction about the origin of the building materials, the company initially was open to answer our questions. However, when we alluded to some specific building materials, generally produced by the businesses of the Orbán family, the attitude of the company suddenly changed: It refused to respond our questions, citing rules of business confidentiality.

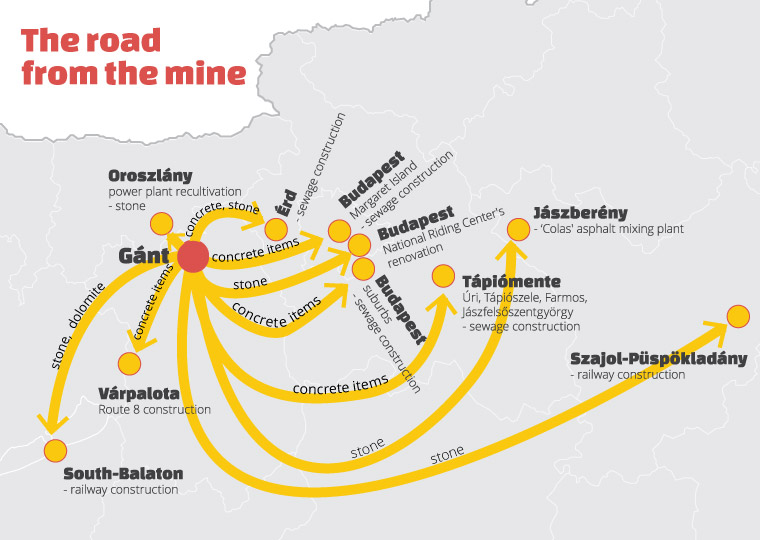

The mine company and other businesses owned by the members of the Orbán family have shown a spectacular growth in recent years. Direkt36 has revealed in previous articles that the Orbán companies’ involvement in several state projects, including motorway, railway and sewerage system constructions, has contributed to their outstanding performance.

The companies participated in the projects as suppliers, delivering building materials. In 2001, during his first term as prime minister, Viktor Orbán explicitly asked his father not to sell materials for large-scale state-funded projects carried out that time. This June, Direkt36 confronted Orbán with the current situation, to which he gave a rather contradictory argument. On the one hand, he said that he still considers it important for his father not to participate in public projects. Orbán’s answers, at the same time, also suggested that he thinks that if his father does not participate in the project as a main- or subcontractor but as their supplier, that is not problematic.

Similar to higher level participants of state projects, suppliers also receive public money, but their involvement remains hidden from the public eye. Public documents do not reveal the identity of the companies that supply building materials, nor the amount of public money paid for their services. Thus, it took us several months of research for Direkt36 to reveal the involvement of the Orbán companies in state-owned projects. We have faced various obstacles during our investigation, and the South-Balaton is an outstanding example of how public institutions and contracted companies try to hide information.

We can only do this work if we have supporters.

Become a supporting member now!

The PM’s old friend at Lake Balaton

The renovation of a 53-kilometer-long railway line on the Southern side of Lake Balaton started last spring. To be completed by next autumn, the project is expected to reduce travelling time on the refurbished line by 10 minutes.

The final budget of the investment is HUF 72.4 billion (€232 million), HUF 16.9 billion (€54 million) higher than originally estimated. 79 percent of the project is financed from European Union funds. The public procurement was won by a consortium of three companies: R-Kord Építőipari Ltd., V-Híd Ltd. and Swietelsky Vasúttechnika Ltd.

- R-Kord is owned by Lőrinc Mészáros, the Prime Minister’s friend, whose wealth increased massively over recent years.

- V-Híd Zrt. is majority owned by István Sárváry, former deputy state secretary. V-Híd, founded in 2015, also won another railroad construction project worth HUF 74.9 billion (€241 million) this summer, in a consortium with Mészáros’ firm.

- Swietelsky Vasúttechnika Ltd is a Hungarian subsidiary of the Austria-based Swietelsky Group, a frequent winner of public tenders in Hungary.

We revealed in our previous articles that Mészáros had previously worked together with Dolomit Ltd., owned in majority by Győző Orbán. Mészáros’ firm bought manhole elements from the PM’s father for the sewerage system construction in several districts of Budapest. We have also shown that Swietelsky Magyarország Ltd. was one of the clients of another business interest of the Orbán family, Gánt Kő Ltd.

The father’s mine

Several sources from the construction sector told Direkt36 that the mining company of the PM’s father is among the suppliers of the Balaton railway project. In the past months, we have visited the site several times, where several workers confirmed this information.

In mid-June, we asked some workers during their lunch break whether they knew which mine supplied the crushed stones used for the project. “Ask Orbán’s father,” one of them replied, and later on we received similar responses at other locations as well.

On the same day, in the consortium’s project office located in Fonyód, two employees also confirmed that the crushed stones came from the mining company of the PM’s father. “They brought 0/32 crushed stone,” said one of them, using the code to specify the size of the stones. However, they did not want to answer our further questions, as they said that they were not authorised to talk to the press.

On 9 November, a man called “smaller boss” by his colleagues, said that as far as he knows, the crushed stones are not delivered from the mine in Gánt. He added, however, that the PM’s father delivers dolomite, which is used for the so-called PSS material, placed under the layer of crushed stones.

We returned to the project office to ask about the involvement of the PM’s father and the PSS material, but we were told that the office “did not receive an authorisation from the corporate level” to answer our questions, and we were directed to the Budapest office of the consortium’s leader, Swietelsky Vasúttechnika Ltd. With this company, however, we already had had a long e-mail correspondence, which took interesting turns over the previous months.

Oh, crushed stones? Then it’s a business secret.

We first sent a freedom of information request to Swietelsky Vasúttechnika Ltd, asking which companies delivered building materials for the project and how much money they received for the services. The project leader replied that he could not comment without the permission of the NIF National Infrastructure Development Company, a state company responsible for public road and railway development projects.

In order to facilitate the process, we asked for the written permission from NIF. The state company gave its approval, which we then forwarded to Swietelsky. With the permission in hand, the company seemed to be ready to answer our questions. The company only asked us to specify the exact type of building materials we were interested in, and to indicate the deadline for our request.

Do you have an important story?

Share it with us on secure channels!

After we replied that we would like to get information about the supplier of crushed stones, the company suddenly changed its mind. They replied that “after having consulted with the consortium partners and with the management of the Swietelsky group” they concluded that they “treat the requested information as business secrets”. The company also put forward a new argument: according to them, only public bodies are required to answer public information requests, not private companies.

But this is not the case. In 2014, an amended legislation stipulated that private companies contracted by the state or by local governments are also required to provide information about how they manage public money, and only in exceptional cases can they classify this information as business secrets.

We sent this amended legislation to the company. After almost a month of waiting for the reply in vain, we wrote to the company that according to our information, crushed stones and dolomite used for the project were supplied by the mining company of the prime minister. We asked the company to confirm or comment on the information, but we did not receive any response. We also contacted the PM’s father, but he did not reply to our questions either.

Nobody knows about the suppliers

This example shows that even after a several-month-long correspondence with the main contractor, it is not certain that it will provide official information about the project suppliers. And we are interested in more than one public project.

In July, we submitted public information requests concerning several major, EU-funded road and railway construction projects – worth a total of several hundred billions of forints – to two state bodies: the Ministry of National Development (NFM) and to the NIF National Infrastructure Development Company.

The ministry is the managing authority in these EU projects: it monitors the projects and verifies the invoices and other supporting documents attached to the final payment claims of the projects. While NIF is a state-owned company acting as the main developer of road and railway construction projects, often at the request of the Ministry of National Development. NIF is the recipient of EU funds and collects the invoices and documents required for payment claims. Both bodies claim, however, that they do not know which companies deliver the building materials for the state projects.

NFM wrote that all data concerning the subcontractors and suppliers of the projects are not managed by the ministry, but by the beneficiary of the EU funds: NIF.

NIF, on the other hand, claims that it does not have data on the suppliers either. In its response to our public information request, NIF said that it has information only about the subcontractor’s level, but it will charge a HUF 246 000 (€790) fee to send it. In August, we launched a lawsuit against NIF with the help of the Hungarian Civil Liberties Union. In mid-November, the court of first instance ruled that NIF has to provide data both on subcontractors and suppliers, free of charge.

András Pethő contributed to this article.

For the Hungarian company data we used the services of Opten.