Hungarians could live 5 months longer, but government halts program tackling air pollution

“We are in the forefront of the climate race, ahead of countries like Germany, the Netherlands or Austria in terms of climate protection policy”, claimed Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban proudly on January 9 at a press conference at his office. The Prime Minister talked a lot about environmental and sustainability issues that day, and he announced a climate action plan. Since then, other members of the government have also been proclaiming that they take climate protection and sustainability seriously.

While Orbán was talking about climate protection, the people of Budapest, Hungary’s capital of 2 million submerged into a dense cloud of smog. The next day, the city’s council ordered a smog alert due to excessive dust pollution.

Air pollution is only a small portion of the problems caused by climate change and economic development. Yet, its impact is enormous and its consequences are measurable in human lives:

- fine particles cause the premature death of 12 100 Hungarians every year

- people living in Hungary breathe the third most polluted air in the whole EU

- Hungary has the fifth most polluted air among OECD countries

The government is aware of the devastating effects of air pollution. Direkt36 learned that five ministries worked on a plan to fight air pollution. At the end of the six-months-long discussion, a draft action plan was compiled that all ministries and non-governmental organizations dealing with air pollution found reasonable.

Experts involved were expecting spectacular results: they estimated that if the targets of the action plan were met, life expectancy in Hungary would increase by 5.4 months by 2030 and the number of premature deaths due to air pollution would be reduced by more than five thousand. However, as Direkt36 was informed by several sources, at the final step before the implementation, the government put the action plan on hold and most of the proposed maesures had been withdrawn.

The plan called National Air Pollution Control Programme (NAPCP) has not been implemented so far. We asked the government about the delay, but neither the Prime Minister’s Office, nor the Ministry of Agriculture, which is responsible for the action plan, responded.

Fine particles enter the body and cause constant inflammation

In total, 12 100 Hungarians died prematurely in 2016 due to effects of fine particulate matter polluting the country’s air, according to the European Environmental Agency (EEA). When it comes to years of life lost, only citizens of Bulgaria and Poland lose more years than Hungarians. In Hungary, 1322 years are lost per 100 thousand citizens.

Air quality highly depends on weather (wind and rain clean the air from smoke) and geographical location (polluted air tends to stay in the Carpathian basin).

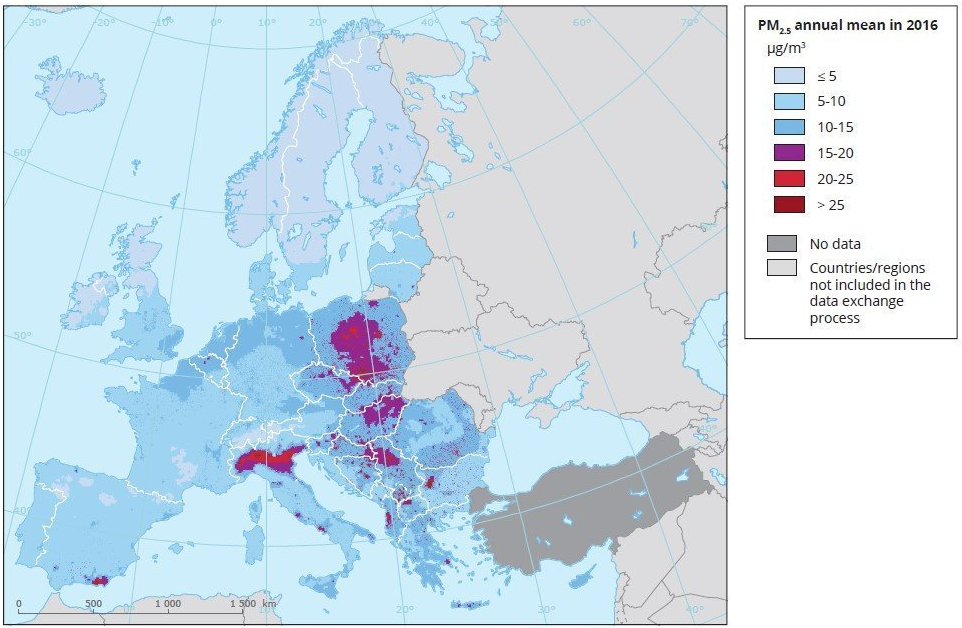

PM2,5 concentration in Europe

In Hungary, the most important factor in air pollution is the amount of fine particulate matter floating in the air. This pollutant is called PM2,5, which means that the perimeter of these particles is smaller than 2,5 micrometers: smaller than one twentieth of a human hair’s perimeter.

Larger particles get stuck in the nasal hairs, but smallers get deeper. This is a huge problem because the surface of these particles catch toxic and potentially carcinogene chemicals, pollens, bacteria and viruses, that can reach the lungs and the most important organs of oxygen exchanges, the alveoli. From here, the tiniest particles get into the bloodstream, and can reach the liver, heart, brain and stay in the tissues.

Particulate matter causes continuous inflammation in the body, respiratory problems, increase risk of cardiopulmonary disease, lung cancer, and worsen the symptoms of asthma and allergies. There is no safe level of PM2,5, even the lowest concentration is dangerous, the longer the exposition is, the more severe are the effects.

PM2,5 has multiple sources: soot from biomass burning of residential heating; exhaustion fumes of vehicles; particulates of car tires; soil resuspension of agricultural activities; chimney smoke of remote industrial areas; it even contains dog, cat and pigeon faeces.

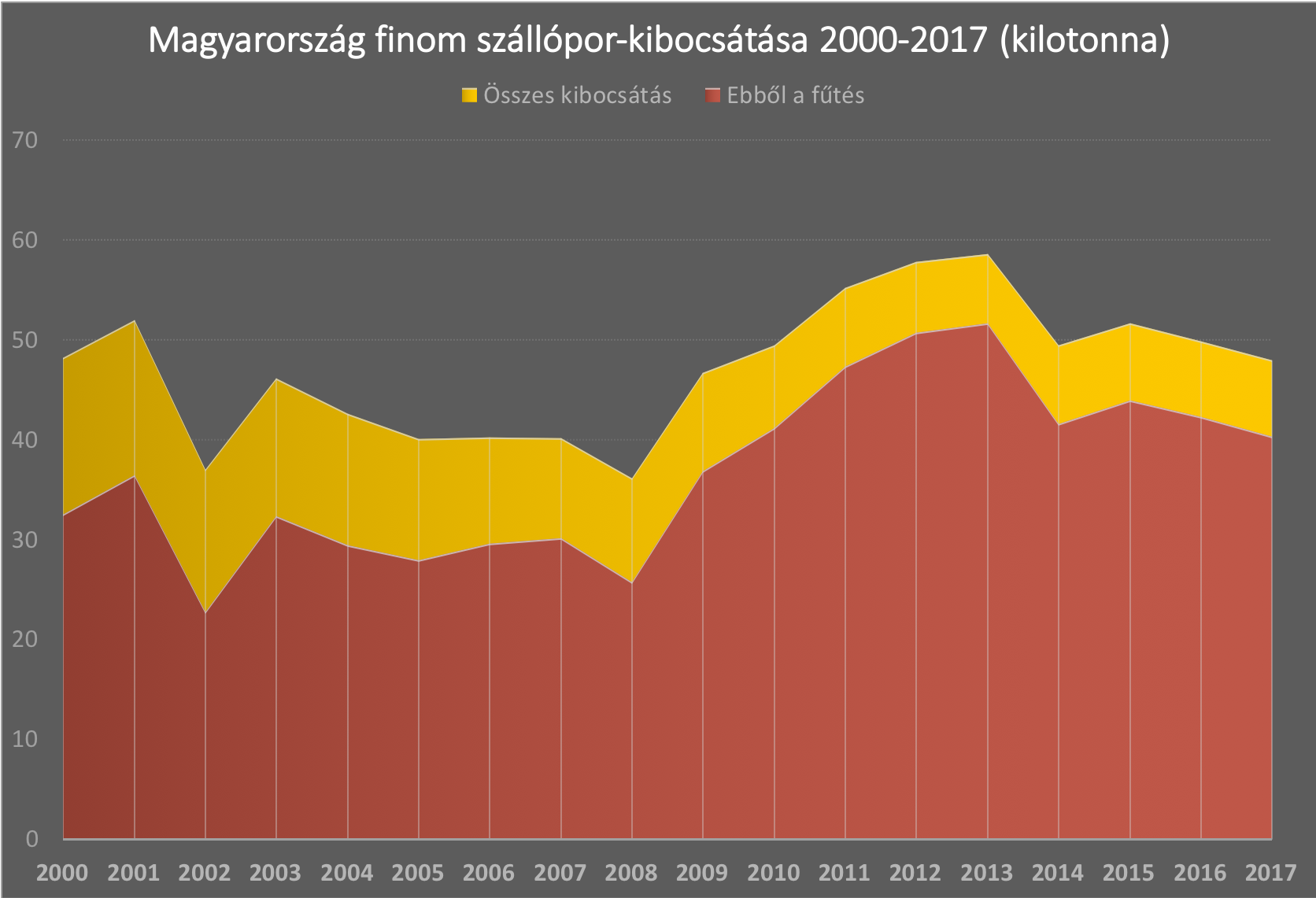

This figure shows the most important source of PM2,5:

Sorces of Hungary’s PM2,5 emission, total compared to the residential heating sector

Residential heating is responsible for about 84 percent of Hungary’s PM2,5 pollution. Biomass burning emits the most: lignite, brown coal and wood combustion. Burning waste adds a whole lot of toxic chemicals to the thick smoke. District heating is the less polluting option, but during the last decades, many households left the system, and many started burning wood. Biomass burning has tripled its share since 2007.

Thick smoke not only comes from old village houses’ chimneys but also from fashionable fireplaces built into houses of the well-off. Therefore, during the cold months, poor air quality not only harms villagers but inhabitants of rich neighborhoods as well. “It is also a problem that municipalities sometimes distribute lignite or coal to the needy, instead of good quality firewood. The most environmentally friendly way of heating is gas heating and district heating”, claims Tamás Szigeti, air hygiene expert of the National Public Health Centre (NNK).

The Prime Minister’s Office interferes

The government worked out an action plan to decrease Hungary’s air pollutant emission, that is called the National Air Pollution Control Programme (NAPCP). An inter-ministerial committe was formed in November 2018, experts of 5 ministries looked into 400 possible measures and chose some of them to include in the NAPCP. There were measures in the fields of residential energy efficiency, traffic, agriculture and so on.

“In order to reach our goals in the case of PM2,5 emission reduction, emission of residential heating needs to be decreased”, states the NAPCD. The compilers must have believed the action plan was consensual, as it was published on the website of a governmental institution. On of the main goals of NAPCP was to start modernizing heating and heat insulation of buildings whereas reducing coal and wood combustion.

The first draft of NAPCP was ready by last spring. This one contained ten measures in the field of residential energy efficiency. Among them was making the social biomass distribution system more environmentally friendly, which would have meant stopping the distribution of lignite and brown coal. One point was “limiting residential use of certain solid fuels, setting quality requirements”, and launching an environmentally friendly social rental housing program. It also planned to reintroduce regular chimney inspections of single-family houses, expand support for heating modernization programs and modernize buildings with heat insulation, window and door replacement and the use of renewable energy sources.

The NAPCP draft was introduced to companies involved in green technologies and environmental protection NGOs: the April 18, 2019 meeting of the National Environmental Protection Council (OKT) was entirely built around the NAPCP. At that time, the government was already under pressure to submit the plan to Brussels by April, as it was the European Commission that had required all Member States to create their own NAPCPsin order to force them to take action to protect the health of their citizens.

“The draft that was presented was good”, said one of the OKT members, Gergely Simon of Greenpeace Hungary. Head of Clean Air Action Group (LMCS) and also OKT-member András Lukács said that the plan “contained effective measures”, although added that there were several important measures missing.

By autumn, NAPCP only needed a stamp from the government. And that is where the process stopped. The Prime Minister’s Office, instead of accepting the plan, ordered the compilers of the NAPCP in the Ministry of Agriculture to cross out most of the residential energy efficiency measures: the ones that were supposed to be the most effective ones in tackling dramatic PM2,5 pollution, Direkt36 learned from several sources taking part in the preparations of the NAPCP. The changes were not strictly kept secret. For example, the Claen Air Action Group was informed about it in a meeting held in the Ministry of Agriculture.

Of the ten measures, only three mildly important stayed. This new, changed draft was publicly presented by the Ministry of Agriculture in November at a conference.

Although the most important measures were out of the plan, most of the ones still in it can help reducing air pollutant emission. For example, the NAPCP contains measures reducing pollution of urban transport and emissions of ammonia from agriculture, which also worsen air quality. A few examples are increasing road tolls, regulating used car imports, modernizing feritliser use techniques in agriculture and reducing ammonia emissions from livestock. These measures are included in the modified version, too.

Two measures removed from the NAPCP – residential heating modernisation and insulation program – have since turned up in another government document: The National Energy and Climate Plan promises to develop a long-term plan to address the problem. But the reduction of wood and coal combustion, which causes the most serious air pollution, has completely disappeared from the government’s plans.

Risky and expensive, but inevitable

To this day, government has not approved even the modified version of the NAPCP. Direkt36 has asked the Ministry of Agriculture, the Prime Minister’s Office and the Cabinet Office of the Prime Minister about the reasons of the delay, but we got no answers.

There might be several reasons behind the angularity of the Prime Minister’s Office, said a source from the Ministry of Innovation and Technology, who is familiar with the subject but wished to remain anonymous. One is that systemic changes are needed to implement the measures that have been removed, for example, in order to persuade hundreds of thousands of households to environmentally friendly heating methods. Other measures, such as the mass construction of zero-energy social housing, are very expensive. The implementation of the original plan would have been politically risky: the elimination of coal burning, for example, would hit the poorest, whose survival often depends on the social fuel provided by the municipalities.

In addition, none of the EU member states can fully comply with EU’s air quality regulations. Apart from Hungary, seven member states failed to present their NAPCPs in time to Brussels. Hungary did send a preliminary draft to Brussels, but still needs to submit an approved NAPCP. Meanwhile the EU’s patience is waning; in 2018, the European Commission has filed a suit against Hungary because of the heavily polluted air in Budapest, and the Sajó valley. The EC’s goal with the lawsuit was to “protect EU citizens from air pollution”.

With the procastination at finalizing the NAPCP, Hungary risks a second lawsuit, as the plan should have been submitted by last April. Although the Council hasn’t yet taken any steps because of this delay, if it decides to do so, the case will be filed to the Curia of the EU straightaway, instead of starting a regular infringement procedure, confirmed Balázs Lehóczki, a spokesperson for the Curia. This would mean that Hungary had to pay a fine for the hesitance of its government.