Inside Viktor Orbán’s Response to the War in Ukraine

Viktor Orbán was preparing for an important meeting that would attract international attention, but things did not go according to plan.

The Hungarian prime minister traveled to Moscow at the end of January, under the shadow of the threat of war, to meet Russian President Vladimir Putin, expecting to bring a delegation of a few people to the talks scheduled for February 1. Foreign Minister Péter Szijjártó and Orbán’s senior adviser on Russian affairs, János Balla, who also previously served as ambassador to Moscow, were among those who were due to attend. But the Russians told Orbán at the last minute that only he and his interpreter would be allowed to attend. According to sources familiar with the details of the meeting, the Hungarian delegation was surprised by this, as it is not customary in diplomacy to impose such conditions at such short notice.

The Russian procedure seemed to have been tightened up for fear of the COVID-19 virus. The hosts insisted, for example, that several covid tests be carried out on members of the Hungarian delegation, including Orbán. The Hungarian prime minister agreed to be tested and had no concerns that the Russians might obtain sensitive biological information about him. (French President Emmanuel Macron, who arrived in Moscow a few days later, reportedly rejected the Russian PCR tests on this ground.) Orbán also had to isolate himself, meaning that there was a period when he was not allowed to interact with others before the meeting. Even after these precautions, the meeting was under special circumstances.

It was the first time that the world had been able to see the famously long table at which the Russian president, who was said to be extremely wary of viral threats, later received several other foreign leaders. Orbán and Putin thus took their seats about 20 feet apart, but spoke to each other in a distinctly cordial tone, making a point of greeting. In his introduction, Orbán, who was seated at the right end of the table, leaning over a small notebook, thanked the Russian president in particular for his help with Sputnik V vaccines during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The two leaders ended up talking for nearly five hours, much longer than originally planned, which Orbán himself described in an interview with the Hungarian state media afterwards as a “serious challenge”. Only a few minutes of video footage of the meeting have been released, but sources familiar with the details of the talks said that the entire meeting was mainly about business between the two countries and was “very technical”.

Orbán was primarily interested in whether he could secure enough natural gas from Putin at a reasonable price amid the deepening conflict between Russia and the West, while the Russian president was concerned with matters of commercial importance to his own country. Putin, for example, spent a lot of time on the Paks II nuclear power plant project, which is to be built by Russia’s Rosatom but has been stalled for years now. According to a source, he clearly knew the “last post-construction detail” of the project, asking Orbán

“how this and that phase is going, and who is responsible for the approval of what and when.”

Also on the agenda were several joint Hungarian-Russian railway projects, but the conflict in Ukraine, which was escalating at the time, was also discussed. In his introduction, Orbán said that this was their “most exciting” meeting so far, and said that his visit was “partly a peace mission.” Putin, in the public part of the meeting and in the press conference afterwards, simply repeated his statements that NATO and the United States were ignoring what he said were Russia’s legitimate security demands.

Although Orbán claimed at an event in Berlin in October that he had seen Putin’s determination and therefore felt “there was trouble coming,” government sources say the Hungarian prime minister said the exact opposite in February, right after their meeting. At that time, to his inner circle he said that he did not expect a war, and especially not one against the whole territory of Ukraine.

In recent months, Direkt36 has spoken to nearly 40 people, including Hungarian government sources and officials from foreign governments, who have insight into how the Orbán government has maneuvered so far in the conflict that has shaken the whole world.

Our investigation has revealed that the entire Hungarian government was unprepared for war, with intelligence services predicting even the day before the invasion began that there was only a minimal chance of war and that a conflict would be limited to eastern Ukraine. When the war started, the government initially did give signals to its Western partners that suggested a possible break with years of pro-Russian policy, but this ultimately proved to be a very brief hesitation.

The government has apparently decided to continue the policy of the past twelve years of becoming increasingly friendly towards Russia and increasingly critical of its Western allies. Although Orbán has voted for most of the EU sanctions, his government has launched a massive communication campaign against the measures, and statements by leading politicians and party propagandists clearly blame the West for the outbreak of the war. In the meantime, the government’s main priority has become to do everything possible to obtain gas from Russia, and the government is not bothered by the fact that, as one source put it, they are being “bullied” by the Russian side. (We sent detailed questions to the government days ago but received no response.)

The war is far from over, but the first six months or so have already seen many twists and turns for Hungary. The following chapters tell this story.

I. THE WARNING

Orbán and Putin on February 1. – Source: Hungarian government

On February 23, 2022, at 10 a.m., the Hungarian parliament’s national security committee, which has four members of the governing party and three opposition MPs, began a closed-door meeting with briefings by the heads of the Hungarian intelligence services. At that time, international media was already full of intelligence reports – mainly from Western sources – that Russia could launch an attack on Ukraine at any time. The committee members were curious to know what information the Hungarian agencies had.

The participants paid most attention to the thorough assessment of the situation by János Béres, Director General of the Military National Security Service (Katonai Nemzetbiztnsági Szolgálat, KNBSZ). The military intelligence service, headed by the buzz cut, gray-haired lieutenant-general, cooperates most closely with NATO partners – even in operations against Russian spies – and is therefore considered more credible by the opposition.

Béres’s account sounded fairly reassuring. He gave little credence to the likelihood that Russia could launch a full-scale, all-out war, or that Kyiv could be attacked. He did point out that the United States expected a total Russian invasion but made it clear that his agency had come to a different conclusion. One of the reasons he gave to MPs for this was that the vast majority of European partners, including the German intelligence service, did not believe the US forecast. According to a source, Béres mentioned that the Orbán government’s regional ally Poland, however, tends to share the US position.

At the same time, Béres saw a growing possibility of a military conflict confined to eastern Ukraine. This seemed a more likely scenario because, a few days earlier, Russia had recognized the independence of the Luhansk and Donetsk provinces, which it had already tried to secede. Such a war, confined to the eastern and southern territories, was later mentioned as a theoretical possibility by Károly Papp, then State Secretary for Internal Security at the Ministry of Interior. Other agency heads also assessed the situation at the meeting that a comprehensive, complex Russian military operation against Ukraine as a whole was not expected.

Less than 24 hours later, in the dawn of the next day, Russia launched an attack on Ukraine. They targeted the capital, suggesting that the Russians were preparing to take over the whole country.

Although international media reports indicated that many other EU countries were skeptical about the threat of war, mainly voiced by the United States, the Hungarian government was particularly unconvinced. Zsolt Bunford, then Director General of the Information Office (Információs Hivatal, IH), which is responsible for foreign intelligence, also questioned the American reports. According to a source familiar with the proceedings of another meeting of the national security committee, Bunford claimed that America was ‘spreading fake news to the Hungarian public that Russia wanted to go to war’. The statement shocked opposition MPs, with several of them asking whether the IH had any similar information that Russia was trying to disinform the public. Bunford, it is recalled, then admitted that some Hungarian journalists were operating under Russian influence.

Hungary’s spy chief did not name the journalists, but the most vocal proponent of the Russian position was by then clearly the Orbán government’s propaganda machine. Since the end of 2021, pro-government media had already been stressing that Putin certainly did not want to go to war, and that the US was only scaremongering. This information was given directly to the various Fidesz propagandists and pundits by the Hungarian government. One opposition politician with good Fidesz connections said that he had seen emails with official ministry letterheads about the current set of government slogans and panels that the Cabinet Office of Prime Minister – headed by Antal Rogán – sent out on a regular, sometime daily, basis. According to the politician, this was also the reason why a well-known pundit, Dániel Deák, who broadcasts pro-government messages on Facebook, “confidently thought there would be no war”.

Deák was not alone with this opinion in the pro-Orbán propaganda machine. “Russia is not going to attack Ukraine, even an idiot knows that. (…) America is saber-rattling, and it is obliging both NATO member states and the European Union to do so, so to speak, by exerting not so gentle pressure”, government propagandist Zsolt Bayer said on a Hír TV talkshow on January 30. According to a former state secretary of the Orbán government, it is worth paying special attention to Bayer, because, apart from the fact that “he would not have made a fool of himself in public,” the pundit has such a personal relationship with the prime minister that these issues are also discussed between them. (Bayer did not respond to our request for comment.)

After the Orbán-Putin meeting on February 1, the Hungarian government appeared to be calm. The Hungarian prime minister returned home from Moscow with the impression that there was little chance of war, or at least that was the impression that emerged from his remarks within the government. At the time, for example, two ministers told a mutual acquaintance that “it seemed to Orbán from the meeting that Putin did not want war.” And a source with close ties to the foreign ministry recalled at the time that there was great relief both within Orbán’s staff and the wider government that there would be no war.

“Putin’s reaction reassured them. It was a big sigh of relief,” the source said.

Orbán also struck an optimistic note at a closed-door meeting of the Fidesz party’s parliamentary faction in Balatonfüred on February 16-17. The ruling party always prepares for the parliamentary season with a multi-day meeting, and Orbán usually holds a speech reviewing the political situation on the evening of the first day. This was also the case on February 16, when participants were especially looking forward to Orbán’s speech because of the upcoming elections. Although one politician recalled that the possible Russian invasion was not the central theme of Orbán’s speech, he did point out that there was little reality of war breaking out. (Well-connected political analyst Gábor Török received similar information. He wrote in a Facebook post after Russia’s attack on Ukraine that Orbán did not list war among the risks in his speech at the parliamentary faction’s meeting).

By then the United States was already warning on a daily basis in public that Russia was preparing for war. However, the entire Hungarian government was critical of these American warnings. According to an analyst working for the government, in those weeks the Hungarian administration “watched US actions with irony.” They viewed the American reports as deliberate disinformation, and, in internal communications, government officials mockingly asked each other when the war would break out. (“This did seem funny until the war actually broke out,” the source added.)

Meanwhile, in closed-door talks, the United States tried to convince Orbán’s aides that they should not believe Putin because he was really going to invade Ukraine.

According to a source with information on US-Hungarian relations, the US had not only shared military intelligence through the central, official NATO channels. According to the source, written notes from the US Embassy in Budapest were already being regularly submitted to the foreign ministry by November 2021, which forwarded them to other ministries. On some occasions, the Americans also directly informed the prime minister’s staff about Russian war preparations. However, the alarming notes and verbal persuasions proved ineffective.

Members of the prime minister’s staff and foreign ministry officials listened politely to the warnings. Then they repeatedly said that they understood the information, but that they still did not believe Putin really wanted to go to war. The skepticism was particularly overwhelming in the foreign ministry, led by Péter Szijjártó.

“The MFA leadership seriously believed themselves to be ‘Russian whisperers’. Stupid Westerners don’t understand the Russians, but they do,”

a source familiar with the foreign ministry’s internal affairs explained their thinking.

Skepticism about the US was also fueled by the intelligence blunders the US has made in recent years, for example in the run-up to the Iraq war or during the withdrawal from Afghanistan. However, Orbán’s staff not only ignored warnings by the Biden administration, which has often been critical of the Hungarian government, but also by the United Kingdom, who were considered as close political allies.

Conservative-led Britain also regularly shared intelligence reports on Russian intentions to wage war, and British Ambassador Paul Fox sometimes teamed up with US Chargé d’Affaires Marc Dillard to try to persuade Hungarian government officials. Britain also used political heavyweights. The day before Orbán’s meeting in Moscow, on January 31, British Defence Secretary Ben Wallace arrived in Budapest, and on February 24, then Foreign Secretary Liz Truss (who later became Prime Minister for a short period) was scheduled to visit Budapest – a trip that had to be cancelled at the last minute precisely because of the prospect of war.

But there were other reasons why the leadership in Budapest misjudged the situation. The prime minister’s staff and the foreign ministry headquarters in Bem Square had long received highly self-censored reports from the Hungarian embassies in Moscow and Kyiv.

“Many times, diplomatic cables sent home were conflict-averse, seeking to meet the perceived or real expectations of the ministry’s leadership,” a source familiar with the internal affairs of the foreign ministry said about cables sent by the Hungarian Embassy in Moscow, headed by Ambassador Norbert Konkoly. Another source familiar with the documents written by Ambassador to Ukraine István Íjgyártó pointed out that these were usually he-said-she-said-type cables, where different reports on who was saying what about the chances of war were collected, but the author of the cable did not dare to take a position.

By mid-February, the Orbán government had reached the point where it was beginning to see the situation as somewhat gloomier. At that time, for example, the prime minister’s staff received a written note from Western intelligence. This report warned that the Russians were already building up a force to strike, and that the Kremlin was trying to fabricate a casus belli that it was actually Ukraine preparing to attack the Russian-speaking population of the Donbas.

Orbán’s foreign policy team had a different reaction, and the chance of war was not completely swept off the table anymore. According to a source in contact with the prime minister’s advisers, Orbán’s people still did not believe in an all-out offensive, but they thought that there is possibility of a war limited to eastern Ukraine. Their assessment of the situation was therefore similar to the one outlined by the head of military intelligence to the parliament’s national security committee the day before the war broke out.

However, after Russia recognized the independence of the Donetsk and Luhansk provinces on February 21, the threat of war became much more obvious than before. Thus, when the Russian invasion finally began three days later at dawn, the governing Fidesz party’s campaign operations, focused on the forthcoming parliamentary elections in April, were able to give a political response relatively fast.

II. THE OPPORTUNITY

Orbán did not believe the Americans – Source: Orbán’s Facebook page

In the early afternoon of February 24, a few hours after the outbreak of the war, the minister in charge of the Prime Minister’s Cabinet Antal Rogán summoned the people operating the government propaganda machine to the Cabinet Office of the Prime Minister.

Rogán, who is responsible for government communication and substantial election campaign topics, gathered the leaders of pro-government media and the pundits whose job is to explain the government’s position to the public, and briefed them on the communication strategy in response to the war. According to a government source with knowledge about the meeting, Rogán spoke of the war as an “opportunity.” He said crisis situations usually strengthen incumbent governments. And Orbán, according to Rogán, is usually performing well in such situations, just like he did during the COVID-19 pandemic, visiting hospitals and receiving airport deliveries.

Rogán was not only speaking in general terms; he also shared with the participants the central messages on which the government’s communication was to be built in the coming weeks. These included the importance of peace, staying out of the war, and rejecting arms transfers. Based on earlier public opinion surveys conducted by government pollsters, Rogán was confident that these messages had the necessary public support. “The government’s communication was prepared, public opinion was assessed in advance,” a source familiar with the discussion said. According to this source, although there were doubts about the US and UK warnings regarding the war, the government, as a precautionary measure, had nevertheless commissioned surveys on what voters thought about a possible conflict when news of a threat of war began to spread in the beginning of the year. Despite Rogán’s confidence, there were concerns within the ruling Fidesz party regarding the war.

“At the beginning, the war’s impact on the election was unclear,” a senior government politician said.

Before the war broke out, the parliamentary election campaign seemed to be going well for Fidesz. The mood in the ruling party was optimistic at the beginning of the year, as internal polls showed Fidesz was leading by 13 percentage points over the opposition. According to the Fidesz politician, the general perception was that no internal political events could threaten Fidesz’s victory, it could be “only something external.”

Accordingly, for a short while at the start of the Russian invasion, there was a sense of uncertainty about how to deal with the issue. On the morning of February 24, the Hungarian government, known for its disciplined communication, used within one Facebook post the expression “Ukrainian-Russian conflict” as well as the term used by Russian propaganda, “military operations in Ukraine”. In the morning hours, news site Origo, one of the main pro-government propaganda outlets, covered the outbreak of one of the most serious armed conflicts in Europe in recent decades only as a small news item – as shown in the screenshot taken by Telex.

The situation was complicated by the fact that the evacuation of the Hungarian Embassy in Kyiv following the start of the invasion was proceeding in a rather disorganized way. According to sources familiar with the events, reports from the Hungarian Embassy in Kyiv did not indicate the possibility of the Ukrainian capital coming under attack until the last minute. This was not only due to the unexpectedness of the attack but also, according to a source familiar with the internal affairs of the foreign ministry, due to the fact that there were no prepared plans or rehearsed protocols for the case of an evacuation. Meanwhile, on the day of the outbreak of war, foreign minister Péter Szijjártó was holding economic negotiations in distant Bahrain, which, according to the source, also showed how little the Hungarian foreign ministry had anticipated the possibility of the outbreak of a war in the neighboring country.

The government regained the initiative in the afternoon. Prime minister Orbán appeared in a public video posted on his Facebook page where he condemned the Russian aggression, said that Hungary should stay out of the conflict, and ruled out the possibility of arms deliveries to Ukraine. Following Rogán’s presentation of the government’s war-related messages in the Office of the Prime Minister, these messages quickly appeared in all the main channels of government communication. Referring to earlier statements made by the opposition’s prime ministerial candidate Péter Márki-Zay, government politicians and opinion leaders started talking about how the opposition would be sending weapons to Ukraine and therefore dragging the country into war.

In the days that followed, the government relied not only on messages related to peace but also on the results of public opinion surveys on other topics. One of these concerned the domestic perception of Ukrainians. According to one source familiar with the research, it showed that “Hungarian voters do not like Ukrainians.” And this was true not only for Fidesz voters but also for some opposition voters. Dislike among Fidesz voters was caused by discrimination against the Hungarian minority in Transcarpathia (Western Ukraine), while disapproval of some opposition voters stemmed from the fact that during previous parliamentary elections opposition politicians repeatedly spoke about illegal Ukrainian voters who had been transported to Hungary by Fidesz on election day.

Based on that, the government found relatively quickly a way to deal with the war situation in domestic politics. The challenge was how to respond at international level, as the Hungarian government, building a close relationship with the Russians for years, found itself in a new position in the international arena. “There was an exploration of what are the possible options for communication as a NATO member state,” a source close to the government said, and added that the Orbán government was assessing the positions of other EU and NATO members states at international meetings held around the outbreak of the war.

The prime minister’s initial approach was to take side with the allies. Orbán made this clear when Putin recognized the independence of the two breakaway republics of eastern Ukraine on February 21 as a prelude to war. After the EU promised a firm response, Orbán posted on his Facebook page: “I had a phone call with the President of the European Council this evening to discuss the situation in eastern Ukraine. I made it clear that Hungary is part of the common EU position.”

Orbán was also quick to speak out when articles appeared in the international press on February 26 that the Hungarian government did not support Russia’s exclusion from the international interbank communication network SWIFT. “Hungary has made it clear that we support any sanctions that are agreed within the EU, we will not block anything,” the prime minister said that day.

The Hungarian government also tried to show goodwill towards Ukraine. While it had previously blocked Ukraine’s Euro-Atlantic integration, citing the situation of the Hungarian minority, in early March Hungary joined the countries calling for Ukraine’s accelerated accession to the EU.

“After the outbreak of the war, the government’s pro-Russian policy softened a lot. It was under the radar and not at the same speed as other countries, but our starting point was also further away and we were taking smaller steps,” one analyst of Russian-Hungarian relations said about this period.

This development was also perceived by foreign diplomats working in Budapest. “There was a brief window when things could have changed, in the days after the invasion at the end of February, after the outbreak of the war,” one of them said based on meetings with Hungarian government representatives. In these meetings, the diplomats received “a different type of reaction after a long time” on Russia-related issues.

At meetings at various levels, the Russian-dominated International Investment Bank (IIB) was a regular topic of discussion (Direkt36 has covered the bank’s affairs in detail.) The Hungarian government has previously come under heavy international criticism for giving the bank a number of benefits when it moved from Moscow to Budapest a few years ago. The Hungarian government had stood by the IIB despite the criticism until then, but after the outbreak of the war, a senior official of the Orbán government gave “ambiguous messages” to Western diplomats. However, the official did not go so far as to say that they were thinking of leaving the bank.

Following the outbreak of the war, four EU member states – Czech Republic, Romania, Slovakia, and Bulgaria – signaled their intention to leave the IIB. The Hungarian government did not make a similar announcement, but there had been meetings where a state secretary in the Orbán government cautiously noted he expected a position change regarding the bank, according to one participant’s recollection. The source interpreted this as the government considering leaving the IIB.

Another indication that the government was thinking about leaving the IIB was that an official of the Hungarian National Bank told a source in contact with the bank that the government had consulted the central bank on the matter. The Hungarian National Bank, headed by György Matolcsy, recommended quitting the institution, arguing that preserving the membership in IIB carried “reputational risks,” meaning it could damage Hungary’s image. (Responding to our inquiry, the central bank said it “could not provide information on the matter.”)

Although the government did not eventually withdraw from the bank, it initially speculated that it might pay off financially if Hungary avoided conflicts on important issues and followed its Western allies. By then, relations with the European Commission had become strained over the so-called recovery funds. Hungary was to receive around €15.8 billion from the fund set up to alleviate the economic damage caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. The government submitted its spending plan in the spring of 2021, however, the European Commission did not approve it, partly because of corruption risks related to the Hungarian public procurement system.

Following the outbreak of the war, Orbán and his government hoped “that maybe the Commission would reward it for supporting the sanctions,”

according to a senior government official who said the Hungarian government hoped to gain access to EU recovery funds this way.

It turned out relatively quickly that the government would still not get the funds. At the same time, the attitude towards sanctions in Budapest changed and voices within the government critical of the West became louder again.

III. THE WORLD ACCORDING TO ORBÁN

Orbán sent a message to Zelensky after his election victory – Source: Orbán’s Facebook page

In the final weeks of the brutal and aggressive election campaign, there was at least one occasion when representatives of both sides spoke to each other in a relatively calm atmosphere.

That meeting happened on March 21, barely two weeks before the election, when Viktor Orbán held a closed-door meeting in the parliament’s delegation chamber with senior parliamentary officials, including several opposition MPs. Orbán did not go to this meeting at his own initiative, or for some domestic political reasons, but because the forthcoming summit of the EU’s main decision-making body, the European Council, was approaching. Before these EU summits, law requires the prime minister to hold what MPs call the “EU grand council,” a meeting with Hungarian parliamentarians, including the opposition.

Orbán took his seat at the table in front of the ornate podium, with his advisor on European affairs, János Bóka, on one side, and the speaker of the parliament, László Kövér, who is an old ally of Orbán and is known for his strictness, on the other. Kövér could not resist trying to discipline the opposition MPs here either. At one point in the meeting, he told them that they could not make public anything Orbán was about to say to them.

According to several participants, the prime minister spoke at length about how he sees the war situation in an international context. He described the current events as a new stage in a process that has been going on for decades, and in his analysis he mostly criticized the United States.

He claimed that this current conflict is about the US wanting to return to a unipolar world order, and that in doing so “they do not care about Central Europe, they do not care about Europe either.” Orbán said that the Americans want “the EU to become an organization specialized on economy” for the Western world, and they think it should not have any foreign policy autonomy and should not want to conclude separate agreements with China, for example. He added that the Americans want to cut Europe off from cheap Russian energy, which in turn will make European products more expensive and give the US a competitive advantage in global markets.

Asked by an opposition MP why Orbán was so critical of one of Hungary’s allies, the prime minister replied that he believed there was a difference between being an ally and being a subordinate.

“A subordinate waits for instructions, picks up the phone when called from Washington and says, ‘Yes, sir’,”

Orbán said, making it clear that for him this position is not acceptable. He also said that the Americans know that he does not share the US view of world order, so “there is a distrust towards Hungary to begin with.”

Specifically on the war, Orbán said that “Ukraine will not win this war no matter what anyone says.” He also said that Hungarians should not behave like the Poles, who are taking the position that this is their war too, and therefore they are helping the Ukrainians. Orbán indicated that he considered the Polish attitude risky because “the Poles want to push NATO into a military conflict.” Even though he was speaking behind closed doors, he apparently tried to be cautious about the Polish leadership, which has long been a close political ally, and did not criticize them directly.

“We are not Poland. It is not our job to imagine ourselves in the circumstances of someone else, in their moral position,” Orbán said.

Orbán barely mentioned the Russians’ role and did not criticize them openly. When an opposition MP suggested that the Hungarian pro-government media is broadcasting pro-Kremlin narratives, the prime minister rejected the suggestion. He said that in Hungary no one can see anything like in Russian television where they are showing Ukrainian soldiers tattooed with Nazi symbols. He reiterated his view, which he had expressed on other occasions, that the media environment in Hungary was in a better position than in the West, where supporters of political correctness suppressed everything, while in Hungary we have a “pluralism of opinions.”

Orbán also referred to the role of Germany. In the words of one participant, he delivered “the usual Angela Merkel love letter”, praising at length the German governments under Merkel from 2005-2021, which sought to build business-oriented partnership with Russia. (The source, however, noted that Kövér, who was sitting next to the prime minister and was harshly critical of the Western elite, showed his disagreement with the “Merkel love letter,” because during Orbán’s remarks he “made a face as if he was going to vomit”.)

According to one participant, Orbán also spoke about Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky in a very conciliatory tone. Orbán noted, for example, that he did not blame Zelensky for the situation because he could not do anything. According to Orbán, it was the United States that had put Zelensky in this situation.

In public, however, the Hungarian prime minister’s attitude towards the Ukrainian president quickly changed. This started with an open conflict between Orbán and Zelensky three days after the meeting in the Hungarian parliament’s delegation room, on the first day of the EU summit, which started on March 24. The Ukrainian president addressed the EU leaders’ meeting via video link, and in his speech he listed one by one the EU countries from which Ukraine had received assistance. Zelensky left Hungary at the end. “Listen, Viktor, do you know what is going on in Mariupol? (…) And you are hesitating whether to impose the sanctions or not? And are you hesitating whether to let the weapons through or not? Are you hesitating whether to trade with Russia or not? There is no time to hesitate. Now is the time to decide,” Zelensky said.

The Fidesz campaign immediately saw an opportunity in Zelensky’s speech. According to a source close to the government, until then they had been worried about what would happen if the topic of the war, which the campaign machine had been peddling around the clock, did not last until the elections. The government propaganda was largely based on a few controversial quotes from Péter Márki-Zay, the opposition’s prime ministerial candidate, and a few other opposition politicians in February, but these had already been repeated for weeks, from state media to Facebook. The source said that by mid-March, however, Fidesz felt that voters were becoming less and less interested in the topic of the war.

It was in this situation that Zelensky’s remarks at the EU summit gave new ammunition to the Fidesz campaign. From that point on, they not only built their negative campaign on the gaffes of Márki-Zay and other Hungarian opposition leaders, but also focused on the fact that the country’s energy supply was at risk and that they would defend it.

On the day after Zelensky’s message, on March 25, Orbán posted a video on his Facebook page, apparently to send a message to his domestic audience. In this video he said that EU leaders wanted to extend sanctions to coal, gas and oil. “In fact, the Ukrainian president himself, who participated in the meeting via video link, asked us to do the same. We considered this and then refused, given that 85 percent of gas in Hungary comes from Russia and more than 60 percent of oil as well,” Orbán said. He added that energy sanctions against Russia would bring the Hungarian economy to a standstill, which “would mean that we would actually be made to pay the price of the war”.

“The topic has become hot, everyone was talking about it,” a source close to the government said of the Zelensky video and the response to it. Internal pollings of the ruling party also showed that the gap between Fidesz, which had around 50 percent support, and the opposition bloc, which was well below that, had not narrowed. The source close to the government said focusing the campaign on the theme of the war was primarily to prevent undecided voters from siding with the opposition.

The strategy was successful, with Fidesz winning another two-thirds majority in parliament on April 3. Even if there were hopes in some Western European countries – or in Poland, which fully supports the Ukrainians – that the Orbán government would make a turnaround in its foreign policy after the election, the prime minister’s speech on the night of his election victory quickly destroyed these illusions.

“In our battle we were outnumbered like never before. (…) All the money and every organization in the Soros empire; the international mainstream media; and, towards the end, even the President of Ukraine. We’ve never faced so many opponents at once,” Orbán hit back on Zelensky once again.

It was not only the election victory speech, which emphasized fighting against the Ukrainian president, that suggested that the Hungarian government would stick with its longtime foreign policy direction. It soon became clear that the Orbán government was not only concerned about the possibility of energy sanctions in its domestic political communication. Hungary voted in favor of the first four sanctions packages between February 23 and March 15 without any serious concerns. Later, it also supported the fifth package of sanctions on April 8, which now included a ban on Russian ships from EU ports and a ban on Russian coal. The Orbán government was ready to do this also because none of these measures directly affected Hungary. But by then it was clear that the logic of sanctions was moving towards a ban on Russian fossil fuels.

The EU quickly put on the agenda the consideration of cutting off oil supplies. With oil exports accounting for a significant percentage of the Russian state’s revenues, member states reckoned that stopping them might be a way of starving the Kremlin’s war machine. But in Hungary, this would have been a serious blow to the partly state-owned MOL oil company and, through it, to the Orbán government, which immediately signaled its concerns.

The EU would then have given Hungary first one and then two years’ grace period – until the end of 2023 and 2024 respectively – to impose the sanctions. Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission, even travelled to Budapest to convince Orbán of this offer, but he remained adamant. The official reasoning was that because MOL’s refineries can receive only Urals (Russian blend) oil, a technical switch to a different type of oil would cost time and money – 2-4 years and hundreds of millions of dollars, according to the company’s statement.

But there was another reason for opposing the oil embargo. MOL was importing Russian Urals oil, which in general has been cheaper than the Brent oil that dominates the world market and has become even cheaper as Russia has become isolated. The Hungarian oil company was thus a big winner: it made a high profit on Urals and gained a competitive advantage over its rivals who bought more expensive oil blends. It is telling that MOL made a profit in the second quarter of 2022 at a level not seen for a long time. It had a profit before tax of nearly HUF 500 billion (€1.3 billion), which, as economic site G7.hu pointed out, was nearly double the profit of the previous year and four times the profit of two years earlier.

The Orbán government has thus become interested in MOL retaining this position for several reasons. A major factor in maintaining the government’s popularity was the fuel price cap imposed in November 2021, which could only be maintained with cheap Russian crude oil supplies. According to a well-connected energy expert, the Hungarian government would not have been able to implement the fuel price cap as well as a so-called extra profit tax on various companies, including MOL, in the absence of cheap Russian oil.

After nearly a month of debate, the oil embargo was implemented with an exemption – so that the ban does not apply to pipeline oil. After the EU summit, the Hungarian prime minister announced this victory with words that alluded to his commitment to traditional gender roles: ‘father is a man, mother is a woman, fuel price stays at 480 HUF’.

However, watering down the oil sanction with the pipeline oil exemption has not only benefited Hungary, but also Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Poland, and Germany (Poland and Germany have agreed in principle not to take up this option from 2023). An energy expert said that, to his knowledge, several countries in the region have followed a kind of stowaway strategy during the tug-of-war. That is, they let the Hungarian government fight it out and then joined the Orbán government’s initiative.

This maneuver was typical of Orbán’s EU negotiations. According to a government source, the prime minister went along with the embargo debate “because he saw that others were supporting it” and so he had room for maneuver. One such country was Germany, which, according to a source familiar with MOL’s internal affairs, “could be quickly persuaded that the whole region’s fuel supply security was at stake.” Several sources close to the government as well as government officials themselves stressed that the Germans were indeed supporting the Hungarian demands from behind the scenes. (The German embassy said it was not in a position to respond to our questions sent on Thursday morning.)

However, a surprising turn of events followed the EU decision. Two days after the compromise on the oil embargo was agreed at the EU summit, the Hungarian government said that the full sanctions package was unacceptable to them in its current form. The government indicated its intention to veto the sanctions because Patriarch Kirill, the head of the Russian Orthodox Church, would have been on the list of sanctioned individuals. Kirill is believed by the EU to be actively supporting Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and spreading Kremlin propaganda (during the Soviet Union, Kirill was also a KGB agent under the code name “Mikhalyov”). EU officials and the Orbán government then pointed fingers at each other for not having told the other in time that the Kirill issue is not resolved. In the end, Hungary’s push succeeded and helped Putin’s close ally escape EU sanctions.

It was only months later when it became clear what could have led the Orbán government to stand up for Kirill. In August, Russian news agency Ria Novosti reported that the Orbán government had prevented the sanctions against Kirill after the Russian Orthodox Church itself had requested them to do so. Sviatoslav Bulah, secretary of the Russian Orthodox Church’s diocese in Hungary, told the news agency that they had sent an official letter to the Hungarian government asking for protection for Kirill.

In a recent interview with Direkt36, Bulah said that although he did not recall the date the letter was sent, he said that his diocese had appealed directly to the Hungarian prime minister for help, to which “the answer was that the government had made the decision” to protect Kirill. The diocesan secretary said that if the Patriarch had been sanctioned, the next step could be to ban dioceses and churches associated with Kirill within the EU.

After the friendly action of the Hungarian government, Kirill announced that he had appointed his right-hand man, Metropolitan Hilarion, to head the Hungarian diocese. Bulah declined to answer whether this decision was linked to the sanctions case.

The Orbán government’s intervention to save Kirill from EU sanctions has made clear to the international public that it is pursuing a special diplomatic path with Russia. This was made even clearer when they began to lobby the Russians intensively to help Hungary in dealing with the escalating gas crisis.

IV. LIES SURROUNDING NATURAL GAS

Hungarian foreign minister Péter Szijjártó with his Russian counterpart Sergei Lavrov – Source: Szijjártó’s Facebook page

In mid-summer, the government took a drastic step. On July 13, minister in charge of the Prime Minister’s Office Gergely Gulyás announced that the government would reshape one of its most important and symbolic measures: the utility bills cost reduction. So far, households paid government-set low prices for all gas and electricity. The modification requires them to pay “market prices” (in fact, also set by the government) for consumption above the “national average” (also set by the government). “In the current energy crisis, it is simply not sustainable to have unlimited reductions in electricity and gas prices for everyone,” Gulyás stated.

This was a huge change in the government’s position as it had repeatedly stated many times before that the utility price reductions were a solid part of its domestic policy which would be guaranteed as long as the Orbán government remains in power. During the election campaign, the government also repeatedly said that the price reductions were possible due to cheap Russian gas coming to Hungary. And Orbán himself ruled out any changes at his post-election press conference when the negative economic effects of the war were already known. “I had seen politicians changing their policies after an election, but that didn’t end well,” he said at the press conference.

Although Gulyás blamed the war for the partial scrapping of the utility price reductions at his July press conference, the reasons actually go back much further. Gas prices had already started to rise last fall, and the war just accelerated this process.

In 2021, the Hungarian government decided to buy natural gas from Russia in the framework of a long-term gas contract. Under the agreement, Hungarian state-owned energy company MVM signed a contract with Russian gas conglomerate Gazprom in September 2021 to buy 4.5 billion cubic meters of gas per year for 15 years. This volume represents less than half of the annual Hungarian consumption of around 10 billion cubic meters. The government buys a large part of the remaining amount from the market.

“Under the given circumstances it was a good contract, but not a favorable one,” a former government official working on the field of energy said about the undisclosed agreement.

This source pointed out that the price scheme in the contract was based on the market price linked to the Dutch natural gas exchange rate, which is considered the benchmark (this fact was previously reported by several newspapers and finally confirmed by the government in early October). That means that under Hungary’s long-term contract Russia only committed to deliver the promised amounts. The price, however, depends on market conditions, so if the price on the world market goes up, the Hungarian state will have to pay more.

According to a former government official, the Hungarian government did not have much maneuvering space in the matter.

“The Russkies were in the driving seat (…), they were dictating the terms, by and large,”

the source said, adding that the Hungarian side had to agree to market pricing because the Russians had full control over what they do with their natural gas and were therefore in a better negotiating position. According to former and current government sources, Gazprom is not as cooperative as it might appear from Hungarian government communications. “We are not in a privileged position as it might be perceived based on all the cozying up,” one source said.

The market price of natural gas was already high at the time when the long-term contract was concluded. While gas prices on the Dutch stock exchange in early 2021 ranged from €16 to €30 per megawatt hour (MWh), there were days in September 2021 when they exceeded €90. Russia, which plays a key role in Europe’s gas supply, started to increase gas prices even before the war. “They dried up the market. Last fall, it became increasingly difficult to buy gas from the market. They sold less and less gas for free market purchase,” a former government official said regarding the Russians’ actions.

Sources with detailed knowledge of the natural gas market told Direkt36 that the Hungarian government had also noticed this trend. That is why Orbán announced earlier this year that he would ask Putin at their meeting on February 1 to agree to the purchase of an additional 1 billion cubic meters of gas on top of the 4.5 billion in last year’s long-term contract. “We thought that even though the Russians would not sell this amount on the market, but they would give it to us,” one source said of the government’s thinking. Following his meeting with Orbán, Putin said that they would decide on whether to sell the requested additional amount later in April. However, further talks on the issue were derailed by the war that started in February.

After that, natural gas prices hit several new highs. In the days following the Russian invasion on February 24, the price reached almost €200/MWh. By May, the market had calmed down somewhat, with the price falling below €90. Another significant price hike came after Gazprom started restricting gas supplies on the Nord Stream I pipeline to Germany in mid-June, citing technical problems. The price of gas catapulted and reached €170 by the beginning of July. As natural gas-fired power plants play a major role in generating electricity, this also had an impact on electricity prices all over Europe. Moreover, rising energy costs have accelerated inflation too.

Skyrocketing gas prices have made it increasingly difficult for the Hungarian government to maintain their utility price reductions scheme domestically. After the contract with Gazprom was signed in September 2021, Hungarian energy company MVM was actually buying natural gas at a higher price than it was selling it to the Hungarian consumers. As a result, the Hungarian state had to increase MVM’s capital by HUF 208 billion (around €570 million at the exchange rate of the time) by the end of 2021 to make up for the company’s huge losses. Even after the outbreak of the war, Fidesz politicians continued to stand by the ultility cost reduction scheme during the election campaign, but it became increasingly clear that this would only be sustainable at a very high cost. The government did not say how much it was spending on gas purchases, citing business confidentiality, but according to calculations of economic media outlet G7.hu and daily Népszava based on data from Eurostat and the Hungarian Central Statistical Office, the amount was much higher than in previous years.

All these developments preceded minister Gulyás’s July announcement about limiting the amount of gas and electricity available for households at discounted rates.

“The price of gas has increased so much that it could no longer be subsidized from the budget,” a former government official who dealt with energy issues said.

In his July speech in Romania, PM Orbán said that maintaining the energy price reductions would have cost the state 2,051 billion forints (more than €5 billion) in this year. “The Hungarian economy would obviously simply not be able to bear this,” Orbán said.

Cutting state subsidies for consumer energy prices did not solve the government’s energy supply problems, however. Russia’s cutting off gas supplies to a growing number of EU member states over the summer sparked Europe-wide concerns. And the government wanted to avoid supply disruptions in Hungary at all costs. Minister Gulyás partly explained the limitations of utility price reductions as a way to encourage people to save energy. “Our aim is to limit energy consumption where it is possible, because there are energy shortages everywhere in Europe today,” he said at his July press conference.

According to sources with detailed knowledge of the gas market, there would be “brutal economic consequences” if the Russians cut off the gas. The importance of natural gas is shown by the fact that, according to official figures of the Hungarian Energy Authority, annual energy consumption is around 1.1 million terajoules, 33-34 percent of which comes from natural gas. There is also concern about how Hungary will meet the huge energy needs of recent large investments, such as a new Chinese battery factory in Debrecen, which the government has recently announced. “Even in peacetime, this (huge new demand for energy) would be a serious problem,” the source said, referring to the urgency to improve Hungary’s energy infrastructure.

This vulnerability also explains why the Hungarian government has not turned its back on Russia despite the war. Although the conflict has made many areas of cooperation between the two countries, such as joint railway projects, impossible, this has not been the case for energy.

“The pro-Russian policy is currently motivated by the need for natural gas,” a source closely following gas market trends said of the importance of Russian gas to the Hungarian government.

Foreign Minister Péter Szijjártó even accepted to be personally humiliated in order to secure gas deliveries. While EU politicians avoid meeting Russian leaders, the Hungarian foreign minister travelled to Moscow on July 21 to discuss gas deliveries. At the meeting, Szijjártó had to pose for a photo with a smiling Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov. At their joint press conference, Szijjártó listened without a word to Lavrov’s speech about people dying in Ukraine because they were being shot at by “Ukrainian authorities”. Although Szijjártó officially went to ask for 700 million cubic metres of gas on top of the 4.5 billion in the long-term contract, a source with detailed knowledge of the gas market said the real reason of the meeting was to ensure that the Russians did not cut off gas deliveries altogether.

Details of the outcome of Szijjártó’s visit were revealed later. Although Russian gas supplies from Austria are faltering, gas from Serbia continues to flow to Hungary. By August, it turned out that new gas supplies had been purchased. The government first reported in mid-August that it had been able to buy 52 million cubic meters of extra gas from Gazprom. Admittedly, this was not a particularly significant amount as, according to the Hungarian energy agency, average daily consumption in January this year was 51.8 million cubic meters. At the end of August, the government announced the purchase of a much larger quantity, but still failed to reach its original target of 700 million. Meanwhile, sources who follow gas market trends closely say that the Russians could easily deliver this amount in little time if they wanted to.

“We are treated as losers,”

the source said, referring to the fact that Hungary was forced to agree with the Russians on small batches of supplies again and again.

The Hungarian government has asked the Russians not only for extra volumes but also for payment relief, as gas prices continue to spiral out of control. By the beginning of October, it became clear that Gazprom would acquiesce. The deal means that MVM will only have to pay a fixed amount for Russian gas for the winter months (from October this year until March next year). If the cost of gas purchases exceeds this fixed amount, MVM will repay the excess in instalments at a later date. However, MVM will then have to pay interests as well. The details of the agreement were announced by Minister of Economic Development Márton Nagy, who discussed the financial arrangement in Moscow at the end of August.

“We needed this so much,” said an energy expert with ties to the government, assessing the Russians’ concession. Energy imports are becoming an increasingly unbearable burden for the Hungarian state. The Finance Ministry estimates that while 3.7 percent of GDP was spent on energy in 2019, this year, it could reach 15 percent. And gas from Russia is one of the biggest items in this year’s spending. In other words, “the Russians are dictating the terms”, said one source with detailed knowledge of the gas markets, explaining how significant Hungary’s dependence on Russia has become.

The source added that, as long as this vulnerable situation persists, “Hungarian policy will continue to make small concessions to the Russians”. In recent weeks, the government has made several proposals that would benefit Moscow. In early September, it emerged that the Hungarian government wanted three Russian oligarchs removed from an EU sanctions list. Also since September, the Hungarian government has been increasingly insistent that high energy prices can only be decreased by lifting EU sanctions against Russia. And a so-called national consultation (a propaganda campaign with billboards that depict EU sanctions as bombs destroying Hungary) against the sanctions policy has been launched by the Orbán government.

The government is also clearly trying to speed up the Paks II nuclear power plant project, which is important for the Russians, and which Putin highlighted at his meeting with Orbán on February 1. Within the government, the oversight of the project has been handed over to Péter Szijjártó, who has a spectacularly good relationship with the Kremlin. The leadership of the Hungarian team responsible for the construction of the power plant has also been replaced. According to a source with an insight into the project, plans to build the new Hungarian nuclear power plants are still clearly counting on the Russian partners.

“It is not realistic that anyone else would build what is currently planned but the Russians,” the source said.

However, a source with knowledge of the foreign ministry’s internal affairs said that, in theory, the French could replace Russia’s Rosatom in the Paks II project, but that would require a total redesign, essentially starting from scratch.

Ideological convictions are also playing an increasingly important role in the Orbán government’s manoeuvres, alongside economic and energy considerations. In recent months, the already dominant anti-Western and pro-Russian voices in government propaganda have been further strengthened. Some are openly rooting for a Russian victory, and recently a pundit on Hír TV even called for a declaration of war against the United States. Government officials do not publicly express such extremist views, but they do so in private circles.

According to a source close to the government, such comments could be heard even from the prime minister’s closest staff even a few months ago. Some said, for example, that the Russians’ poor position in the war is not the consequence of their own unpreparedness and the decisive military actions of a Ukraine helped by the West, but is deliberate, as Russia is intentionally dragging out the conflict to serve some higher strategic interests. Indeed, there is even a view among Orbán’s staff members, that the real aim of Putin’s war is not to occupy Ukraine, but for Russia to join forces with China and India to dethrone the US dollar-based world economy and create a new financial system.

“I was just staring and thinking, my God, what are these thoughts,” the source said.

András Pethő contributed reporting to this article.

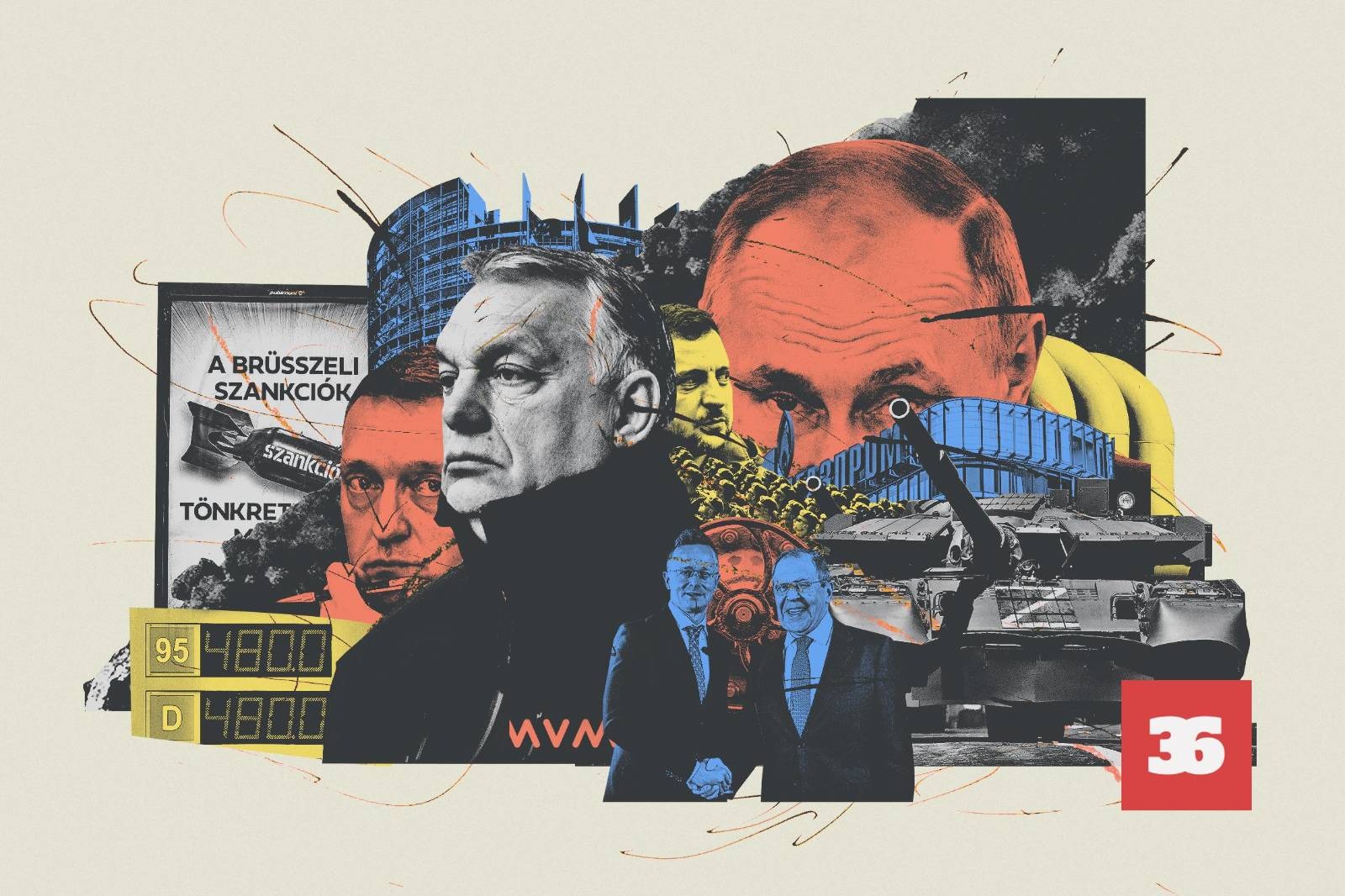

Illustration: Péter Somogyi (szarvas) / Telex.hu