„Read this! It’s crazy!” How the machine of crypto investment fraudsters works

30 phone calls in just two weeks from 20 different British, Swiss and Hungarian numbers. Our reporter was pushed hard to make incredibly profitable online investments. The calls started after we had found a website where Budapest Mayor Gergely Karácsony had shared his secret of getting rich.

The news about the Mayor is of course, fake, as is the investment platform linked to it, where we registered. This is also part of a series of scams that Direkt36 wrote about in the spring as a member of an international journalistic collaboration involving reporters from more than 15 countries. Scammers deceived hundreds of people worldwide, including Hungarians, and deprived them of their savings. Now the same team of journalists, led by the Swedish Dagens Nyheter and the investigative network OCCRP, has uncovered how these scammers scout their victims.

After the articles in spring, a source shared 15,000 online ads with Dagens Nyheter that promised fantastic profits to their victims, citing well-known people. Although the advertisements shared by the source were not in Hungarian, Direkt36 found several very similar Hungarian sites online, as well as people who fell victims of scams through such ads. As we dig more and more into the world of fake news ads, we encountered more and more such pages ourselves.

The stories of similar scams frequently elicit reactions that blame the victims, saying anyone who is so gullible deserves to lose their money. But the whole problem is more complicated than the tragedy of deceived people:

- Scams reached such merits that the Hungarian police gave priority to investigating the cases of the victims

- Fraudsters not only deceive their victims, but also unscrupulously use the names and faces of well-known people (such as Hungarian PM Viktor Orbán, Gergely Karácsony or model Barbara Palvin)

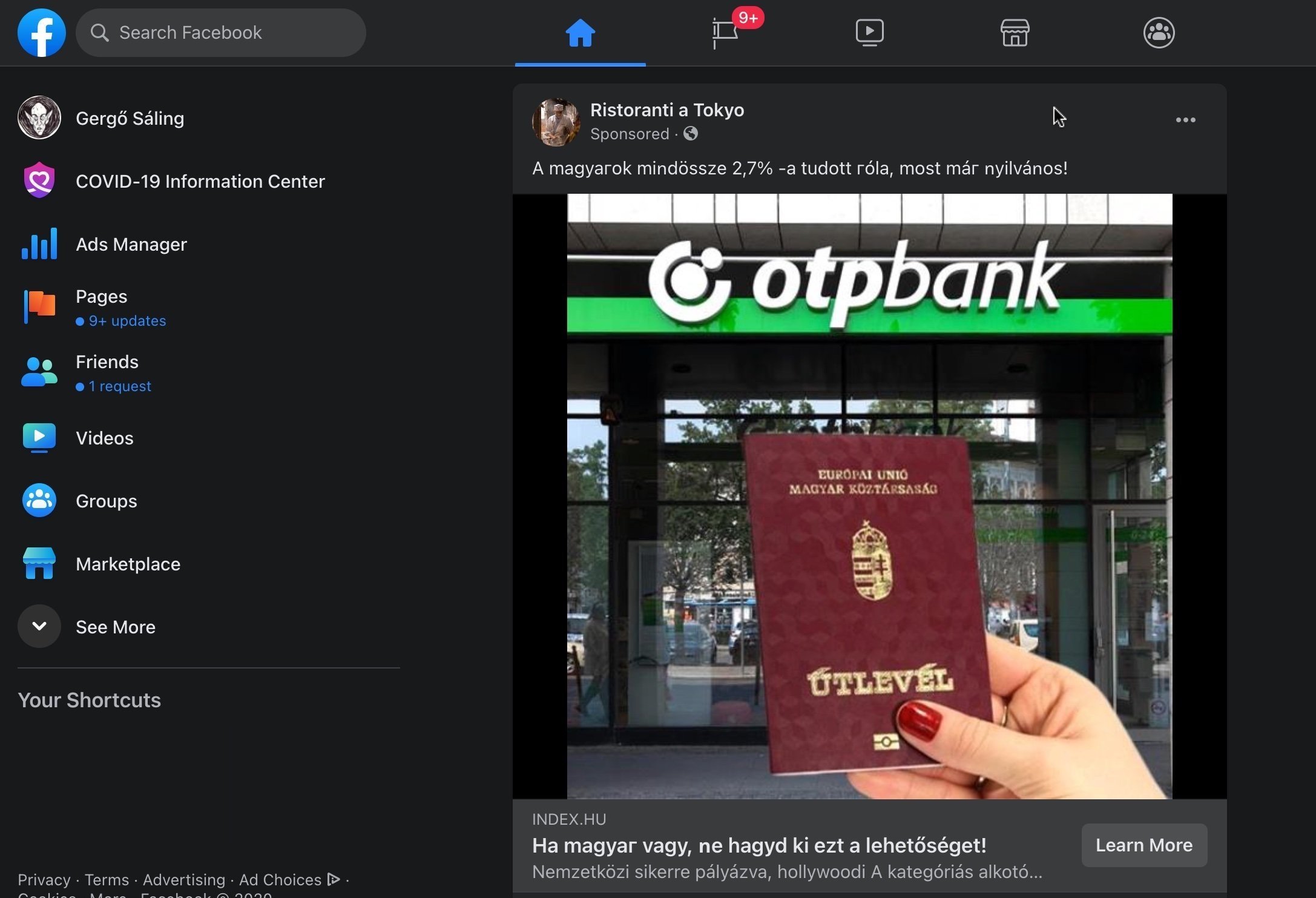

- And for all this, they use the advertising platforms of Google and Facebook, constantly improving their methods which makes them impossible to tackle. While tech firms say they fight sensationalist ads, they also make a lot of money running them.

To better understand how these scams work, we not only talked to more victims, but also registered on one of the fake news sites, advertising a non-existent crypto investment platform. We spoke to a cyber security expert investigating similar scams, a cybercrime investigator of the Hungarian police, and a source who used to be involved in running a fake investment platform. Reporters of the collaboration also approached Google and Facebook to confront the two companies about the severe consequences of ads running on their sites.

Simple cheating with a sophisticated method

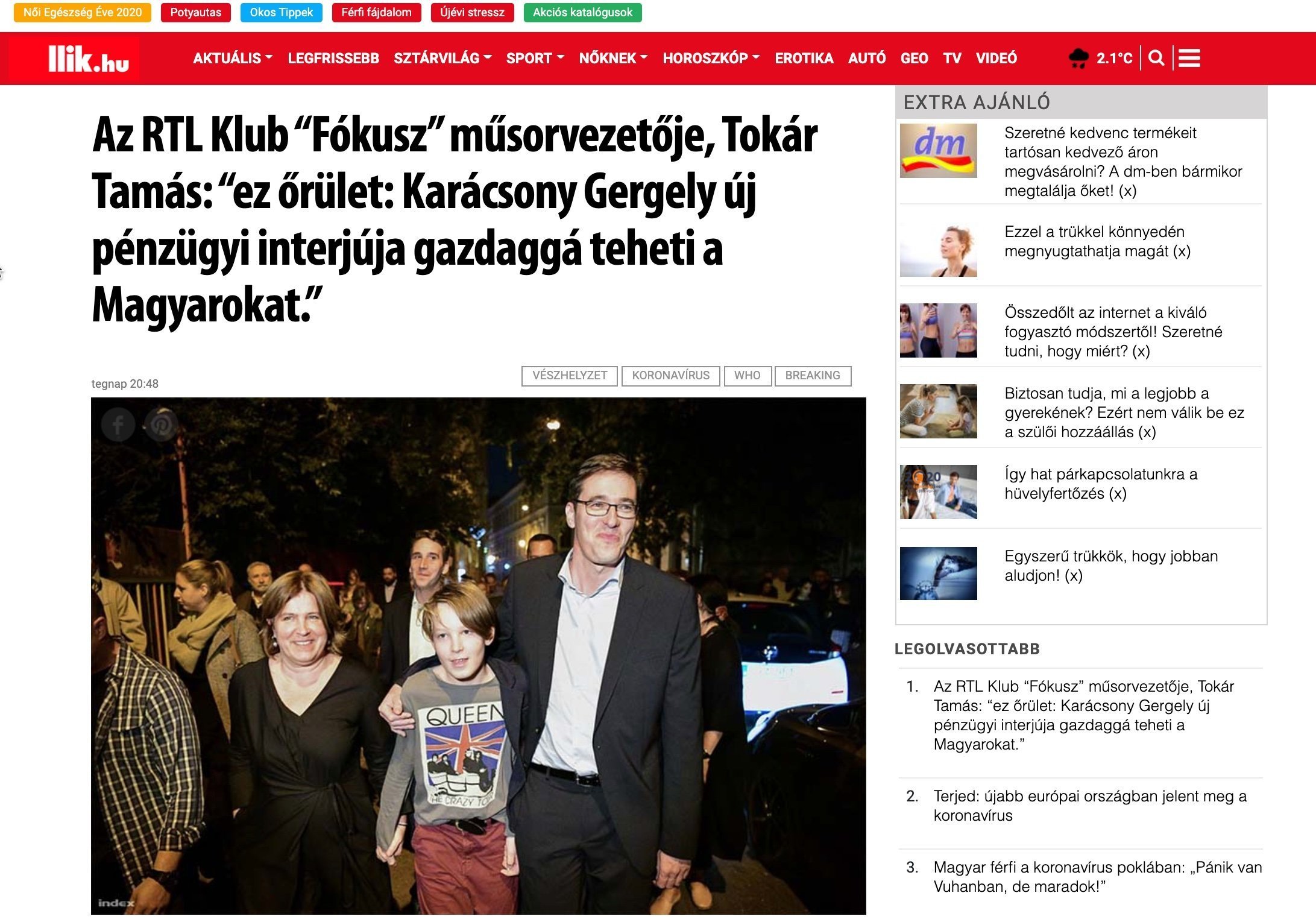

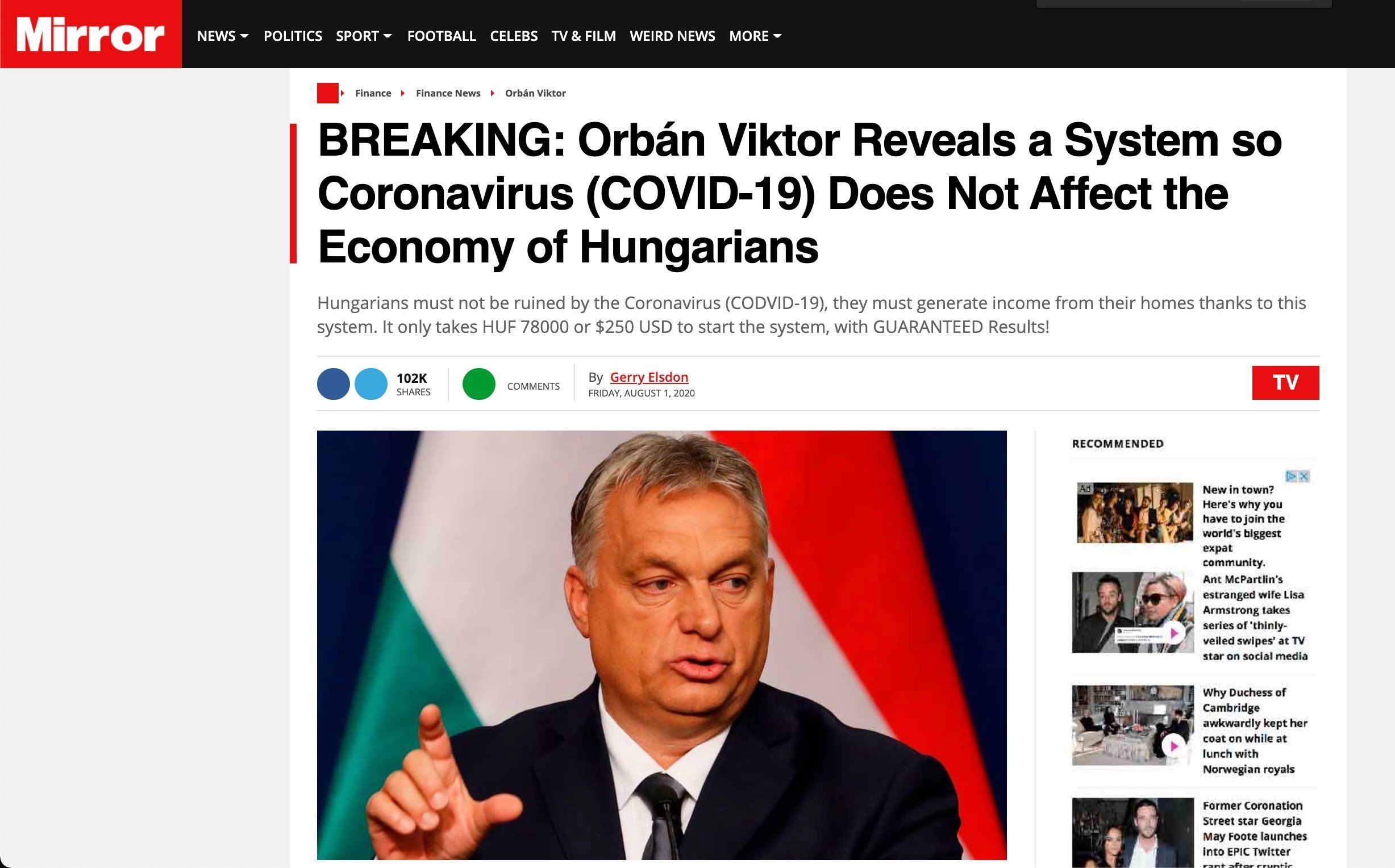

The picture above shows how a typical scam ad looks like. We found it being redirected from a torrent page in the early stages of writing this article. Similar advertisements started appearing on the Hungarian internet around the beginning of this year. This particular ad mimics the website of a Hungarian tabloid called Blikk. There are more professionally made fake ad sites and some of the Hungarian ones we found were still active and promoted on Facebook a few days ago, meaning that they had passed through the company’s filters. The image below seems to show an article of the Hungarian news portal Index, but instead links to an ad misusing the name of Hungarian model Barbara Palvin.

The scam follows a similar logic in most cases and leads through several steps:

- There’s a bombastically worded but meaningless ad on a website or social media.

- It leads to a web page copying the design of an online media site falsely citing a well-known person who claims to have gained huge profits with the help of an advanced algorithm.

- From here, victims are redirected to a registration page, which typically (but not always) includes bitcoin in its name (bitcoin is an online exchange and payment tool that is not regulated by international institutions). Here the names, email addresses and phone numbers of the victims are collected.

A fordításból itt-ott nyilvánvaló, hogy a szöveg fordítóprogrammal készült

- After the registration, an email arrives from a (possibly fake) investment platform, and soon someone is sure to call.

- But after registration, user data is released to the free market and is used by more investment platforms.

The latter shows that sites that collect victim data sell the personal data collected at registration to multiple platforms. Clearly, the system is extremely sophisticated and already involves so many tasks that different groups specialize in each phase. This is also supported by evidence found by other journalists involved in the investigation. These include ads placed on the open internet by people who sell client data for hundreds of dollars to investment call centers (for more details, read OCCRP’s article). But the same was confirmed to Direkt36 by Viktor Halász, an officer of the cybercrime department of the National Bureau of Investigation. According to him, separate groups specialize in collecting data of victims because it is often easier for call centers to pay for the data than to find clients themselves.

After registration, we were called several times from different English, Hungarian and Swiss numbers and offered the services of different investment platforms.

The sophistication of the method is also indicated by the number of people in the fake ads. Among the Hungarian-language advertisements, we found one that advertises the miraculous investment opportunity with Gergely Karácsony and Barbara Palvin, and, in the summer, versions using the names of OTP Bank chairman Sándor Csányi and billionaire Lőrinc Mészáros also began to spread. But an ad mimicking the design of the British tabloid Mirror featured Hungarian PM Viktor Orbán and mentioned coronavirus. This one was in English, thus possibly targeting non-Hungarian supporters of Orbán.

Sándor Csányi has filed a complaint (the Budapest Police Headquarters is investigating on the suspicion of fraud causing significant damage), and Gergely Karácsony intends to report to the police as well.

“Could you send my money back, please?”

Zoltán, a young teacher from Western Hungary, also encountered an advertisement using the name of Budapest Mayor Gergely Karácsony. He is going through the hardest months of his life, having lost all his savings. Heavily indebted, he even had to sell his house. Zoltán saw the ad on Facebook, through which he reached a platform called Bitcoin Revolution.

Zoltán told Direkt36 that he felt that the ad was credible because it was on Facebook and referred to Karácsony. He quickly registered. His phone rang almost immediately. An English-speaking, very helpful man led him through the process: first, asked for his credit card information and asked him to write “I want to buy bitcoin” on a piece of paper, and then make a selfie holding the paper in front of him. He was then asked to install a program called Anydesk that would allow remote access to Zoltán’s computer. Subsequently, Zoltán paid € 250, which seemed to make profit right away: the next day, his balance was already € 1,000.

Between March 23 and April 8, Zoltán paid a total of HUF 12 million, which meant all his savings and an additional HUF 8 million, which he had borrowed from his cousin. The so-called investment advisers always asked him for more and more millions, giving different reasons. For example, “as a guarantee that they will be able to send it back,” or as “collateral security,” but they also said that the coronavirus situation had brought uncertainty into the financial world. The last message from his so-called financial adviser was downright rude.

“I did my job. From now on, you have to solve your own problems yourself,”

he wrote on the 24th of April. He has not answered any messages or calls since then. Zoltán tried one last time in mid-June: “Could you send my money back, please? I have to take care of my son. Please.”

Zoltán felt horribly, he hadn’t slept in days. He took a deep breath and told his wife what had happened, who said that he had done a foolish thing but supported him. They tried to do something together. Zoltán’s account-holding bank, K&H, did not see an opportunity to get his money back, but directed the man to the police. But the police suspended the investigation weeks after his filing a complaint because they could not identify the perpetrator. The couple sold their family house, paid their debts for the price, and moved from the remainder to a flat in town to “climb out of the pit”.

“We call it € 250 scams. In Hungary, about a year and a half ago, reports of defrauded Hungarian citizens began to come from all over the country,”

Viktor Halász, head of the Cybercrime Intelligence Unit of the National Investigation Bureau (KR NNI), told Direkt36. According to Halász, these scams have multiplied since 2016, when the bitcoin price hit hard and many who started trading in the beginning became wealthy. This year, the epidemic helps fraudsters even more because people spend more time online. “The [victims’] stories are similar, and the amount of the first deposit is usually €250, which, among other things, ties them together. This means that the perpetrators are likely to be from the same circle, even if they use different names and company names,” the police officer said.

NNI united the cases in Hungary and started a joint investigation, which shows the seriousness of the problem. Normally, investigation of fraud cases with relatively minor losses belongs to local police stations, and NNI intervenes only in exceptional cases. “We tend to bring similar cases together only when the phenomenon has grown large, affects many people, and the trend cannot be expected to reverse,” Halász described the severity of the situation, although he refused to reveal exactly how many cases they were aware of.

According to Halász, the victims are typically less familiar with the online world, born before the spread of the internet, have little savings, and are often not scammed for the first time. According to the investigation so far, the fraudsters are mainly foreigners, mostly from outside the EU.

„I will keep calling you”

“There’s a text that needs to be learned, and the point is to rip people off,” an Israeli source summed up the essence of the fraud. Four years ago, the source used to work in a call center trying to lure victims from around the world. “When you see the text, the hair will stand on the back of your neck […] Just imagine: [people] paying hundreds of thousands of dollars persuaded by phone calls. Hungarians might only pay a thousand or two thousand dollars, but that’s only because they’re so poor. But what about the Canadians, the Germans?” the source said.

“They register and you have to catch them at the very moment,” the source explained, which is also supported by the experience of Direkt36. One morning we registered on a site called Bitcoin Era, which we reached through an ad featuring Gergely Karácsony and imitating the look of Blikk. At the end of the registration, we came to a page called Unitestocks.

[ifr id=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/L7fX8eVB-hk” align=”center” mode=”normal” autoplay=”no” parameters=”https://youtu.be/L7fX8eVB-hk”]

Registration was completed at 8:42 AM. Less than 2 hours later, at 10:33, we were first called from a British number, but we did not answer that call. 27 minutes later we were called again from another British number, but we didn’t answer that either, which did not seem to discourage those on the line: the phone rang again at 11:39. We then asked for a callback in the afternoon, which a man introducing himself as Kevin Brown willingly did at 12:04. These are 4 calls in just 3 hours.

The man did not fall out of his role even when we told him in another conversation that we know of several cases where people have been tricked in a similar way. “Everything we’ve talked about so far is a real investment […] every transaction, every transfer, every movement in the market, and transfers from your own account to your investment account as well. It does not matter if it is € 1 or € 10,000, everything is checked. You are protected, and [our] company is protected from money laundering,” he explained, not in very good English, but patiently.

[ifr id=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/hULD5T1PuTg” align=”center” mode=”normal” autoplay=”no” parameters=”https://youtu.be/hULD5T1PuTg”]

Not only did Kevin Brown called after registration: three days later, a woman with an impatient tone in her voice called from another UK number and urged to invest. “I am not a customer service manager; I cannot delete your account. My job is to call you when you sign up,” she said, getting nervous. And when we told her we were journalists, she almost shouted, “What are you talking about? I will keep calling you. I will keep calling you.”

But fraud doesn’t just depend on them being pushy. According to our source from Israel, the fake ads and the fake news site are excellently designed psychologically.

“By the time they read through the website, [the clients] are all happy and agitated. The site has evoked emotion,”

the source explained. He found that some clients could hardly wait to pay the first installment when he first called them, while others needed a maximum of 5-10 minutes of persuasion to believe they were in contact with a legitimate broker. Besides, scammers do not easily let go of those who hesitate. Kevin Brown talked to us for ten minutes on the first occasion, then called the next day again to push even further.

“They are not stupid”

It is very difficult to find out who is behind scams like this. Tamás Kocsis, an expert with the Hungarian cybersecurity company Alverad Technology Focus Kft., analysed fake ads using the name of Hungarian billionaire and banker Sándor Csányi.

Kocsis identified a total of 536 pages that promoted an automated, artificial intelligence-supported trading system, promising fabulous profits, which were using the same unique programming interface. The specialist looked into the network several times in October: new pages were added every day, meaning someone kept creating them. Most URLs still work today.

The police are also struggling with this problem. According to National Bureau of Criminal Investigation (NNI) officer Viktor Halász, the biggest problem with this type of fraud is that it is not very difficult for scammers to hide their traces, and although perpetrators will “always make mistakes” sooner or later, if a fraudulent page is blocked, a new one can be created in five minutes.

The registration platforms (such as Bitcoin Era or Bitcoin Revolution) have been subject of numerous warnings by financial authorities in various countries, including Spain, Malta and Belgium and by the National Bank of Hungary (MNB). In addition, the Italian financial regulator has launched an investigation and found evidence that the data of customers registering on a platform called Bitcoin Revolution has been fed to blacklisted cryptocurrency call centers.

However, it is very difficult to prove a close relationship. The images they’re using and the similarities in the code and structure of the pages are the most direct link, but it is not even clear if the registration pages always direct customers to scammers, or sometimes to actual brokers who do invest the money of their clients.

The exposition of fraud is also made more difficult by the fact that there are also companies that engage in similar activities under legal and truly regulated circumstances. In addition, fraudsters are constantly improving the system, and respond to investigations and reports pertaining to their methods. We have even found a recent ad that also led to one of the fake investment sites, which said “Is Bitcoin Loophole a scam? Here is the whole truth”.

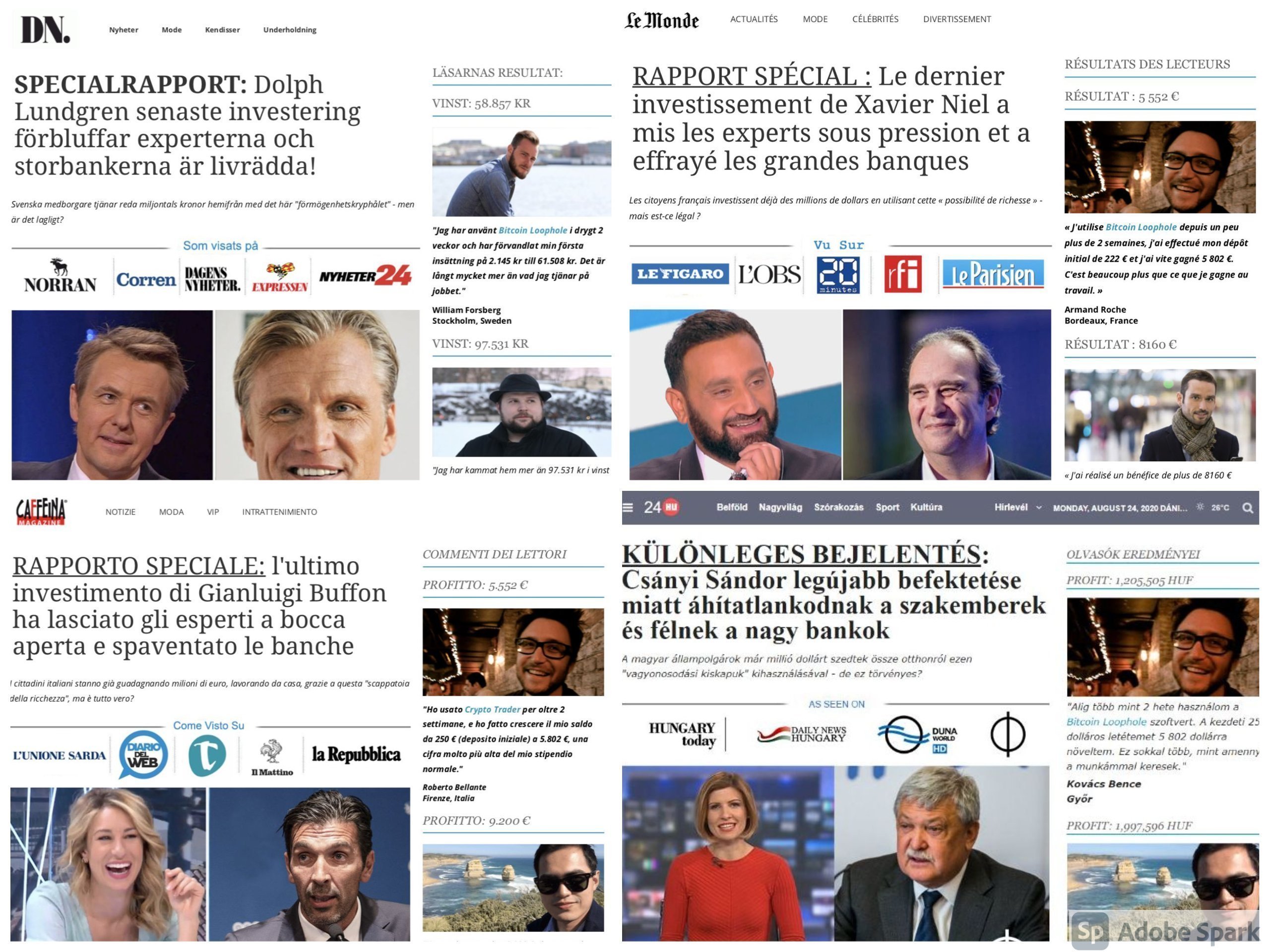

Hungarian-language ads and celebrity news are just a very tiny proportion of the tens of thousands of similar scam sites populating the Internet. These include world-renowned actors, athletes, and public figures (e.g. Jennifer Aniston, Gordon Ramsay, Elon Musk). The British Cyber Security Institute has removed 300,000 of these fake news sites from the internet in four months.

Among the documents obtained by Dagens Nyheter and processed under the leadership of the OCCRP are some 800,000 similar celebrity news in French, English, Swedish, and Finnish, to name a few. These mostly include ads that offer cosmetics or miracle cures to solve health problems, but about 15,000 of them advertise cryptocurrency investments. They are similar in appearance, structure, and content (OCCRP writes in detail about these ads and the company behind them in its recent article).

Source: OCCRP, Alverad Technology Focus Kft./Kocsis Tamás

According to cyber security expert Tamás Kocsis, and judging by their structure, Bitcoin Revolution and similar registration sites also act as commission hubs. “Participants in these networks actively engage in the production of the fake news content, and the placement of ads in exchange for some commission and a shared use of the operator’s infrastructure, templates, and pages,” he told Direkt36.

The system built for the investment scams follows the scheme of affiliate programs well known in the marketing industry. The point of this is earning money by promoting someone else’s product. For example, if an Instagram influencer promotes a product on their site, they will receive money from their site for the traffic directed towards the product’s manufacturer. The more people click through, the more commission is earned.

As an Israeli source told Direkt36, the company he worked for got the leads (contact data of potential customers) from at least ten different sources. Among their partners were marketing companies that advertised a multitude of things and were not necessarily aware of what kind of company the collected customer data would end up with.

After a customer made their initial deposit, a commission went back to the company providing the lead. In each case, that amount was hundreds of dollars more than the amount of the first deposit, and this was the case elsewhere, too. Still, it is worth for the call centers, the Israeli source explained, whose job was to persuade customers to make their first deposit.

“My employer paid $250-1000 for a single customer’s data. It is worth it because even though twenty people may only pay the first $250, but if only four of those go on, and pay another half a million dollar, it’s already well worth it for the call center ”.

At their company, the purchase of customer leads was arranged by company executives, the Israeli source said. They made agreements with their partners via encrypted online channels. The meetings took place in closed Signal and Telegram chat rooms, as the bosses were very careful. “Our boss didn’t even dare to use Windows. These people are not stupid, but highly prepared people who do fear the law and retaliation. Imagine how many people can be angry with the owners? They have ruined lives.”

For example, two years ago the British Financial Supervision Authority (FCA) received only 530 complaints from dispossessed customers, but last year it was already 1834 people. Thus, in one year, victims of cryptocurrency fraudsters were tricked into paying more than £27 million (HUF 11 billion) in Great Britain alone, and even within the country it’s just the tip of the iceberg, as most victims don’t even get to the point of complaining to the financial authorities. The Kiev-based Milton Group call center, a company previously covered by Direkt36 and its partners, OCCRP and Dagens Nyheter of Sweden, generated a revenue of $70 million (HUF 21.5 billion) in 2019, scamming victims from around the world. There may be hundreds or thousands of similar call centers worldwide.

The man using the pseudonym Kevin Brown claimed that his investment firm, Unitestocks is a subsidiary of Safecap Investment Ltd., and thus they operate legally in the EU. To prove this, he emailed us two registration numbers: one issued by the Cyprian, the other by the South African Financial Authority, and they do in fact belong to a Cypriot company called Safecap Ltd. However, when asked by Direkt36, Safecap (which legally provides investment services to its clients, and its owner, Playtech Plc, listed on the London Stock Exchange), stated they had nothing to do with Unitestocks and they do not use fake celebrity ads to advertise their products.

According to its website, Unitestocks is operated by an offshore company called Demure Consulting Ltd. For years now, hundreds of companies with untraceable ownership have been registered under Demure’s Dominican address. Dozens of them operate cryptocurrency investment websites, and at least four of these have already been blacklisted by various financial authorities around the world. We have sent questions about the activities of Unitestocks to Demure’s email address, but there was no response.

Google and Facebook do fight the fraudsters, but also make money on them

The spread of cryptocurrency scam is supported by the highly effective advertising systems developed by Google or Facebook in recent years. Reporters taking part of the investigation found several examples of this.

On interfaces owned by Google, such ads appear in connection with certain search terms or demographics (age, gender, location). When asked by reporters involved in the investigation, the company stated that it has banned 50 million of such sensationalist ads in 2019. However, according to an analysis by Dagens Nyheter and OCCRP, only four websites that recruit their clients with obviously fake celebrity news, have spent $20 million on similar ads this year alone. “This is a cat and mouse game: scammers are constantly evolving their approach to try to beat our systems, but we remain committed to fighting them. We have thousands of people working to improve our enforcement technology and develop new policies to address these threats as they emerge,” Google said. They also added that it is not possible to estimate a company’s revenue based on how much money an advertiser has spent advertising a particular search term, because the actual sum may differ. However, they also did not provide an exact number of how much of their revenue came from ads on the sites examined by DN and OCCRP.

Facebook made a similar statement.

“We don’t want ads seeking to scam people out of money on Facebook – they aren’t good for people, erode trust in our services and damage our business.”

“To fight this, we work not just to detect and reject the ads themselves, but block advertisers from our services and, in some cases, take them to court. While no enforcement is perfect, we continue to investigate new technologies and methods of stopping these violating ads and the people behind them,” a Facebook spokesperson Rob Leathern told the reporters.

The system is indeed far from perfect. One of the bombastic Facebook ads featured in the article first appeared in mid-November, when Hungarian news media reported it was fake. Two weeks later, we also came across the same ad via another Facebook page. There were a lot of comments added to the ad, most of them warning that the whole thing was a fraud, and there was even a user who, according to an uploaded image, already reported it to Facebook almost a day earlier as a scam. Nevertheless, the ad was still active, so are the two pages displaying the fake ads to this day.

The Hungarian police have prepared a guide on how to avoid becoming a victim of internet fraud. And for those who have already been cheated, their advice is to turn to the police.