How an oligarch’s fall made way for the Orbán family’s businesses

After the 2010 landslide election victory of Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz party, several companies with links to government figures have started to flourish. The businesses of Orbán’s father and two brothers, however, began to grow only years later, in 2014.

There was a reason for the delay.

Lajos Simicska, the businessman and longtime ally of Orbán, who helped transform Fidesz into a powerful political force, had been a dominant figure in the construction industry from 2010 until 2014, when he had a falling out with Orbán.

During that 4-year-long period, Simicska, through his companies, had been involved in the majority of major public projects and influenced who else could be part of those works. According to sources familiar with his activities, Simicska and his associates had made sure that the companies of Orbán’s family members received only a limited amount of work in state-financed construction projects.

This practice was primarily aimed at Orbán’s father and two brothers – whose companies deal with mining, manufacturing of concrete products and transportation – but was also extended to István Tiborcz, the then-boyfriend and current husband of Ráhel Orbán, the prime minister’s daughter.

Simicska’s empire, which had been considered by many the symbol of political corruption at the time, did not follow this practice due to selfless moral commitments. They exercised control over the Orbán family’s involvement in state projects in the interest and, according to a source close to Simicska, at the request of Viktor Orbán. The goal was to spare Orbán from similar political attacks he had come under during his first term as prime minister between 1998 and 2002, when he was frequently criticized because of his father’s alleged involvements in public projects.

However, by 2014 when Fidesz was reelected, the alliance between Simicska and Orbán had broken up. This changed the landscape of the construction business. Simicska was not replaced by other similarly influential figure and this gave more room for the businesses of people with family ties to the prime minister in state projects.

The businesses owned by Orbán’s father and the two brothers nearly doubled their revenues by 2015 and their profits was rising even faster. This was made possible at least in part by their involvement in mostly EU-financed constructions, as Direkt36 revealed in a previous investigation. The company of István Tiborcz, who married Ráhel Orbán in September 2013, also gained new momentum in state tenders after he had parted ways with Simicska’s empire.

We can only do this work if we have supporters. Become a supporting member now!

This article is based on conversations conducted with sources close to Viktor Orbán, Lajos Simicska and other, still influential players in the construction industry. They all asked for anonymity because of the sensitive nature of the story. Simicska declined to comment. Orbán and his family members did not respond to the detailed questions Direkt36 sent them.

Party and family

Simicska helped lay the groundwork for the Orbán family’s businesses in the early 90s.

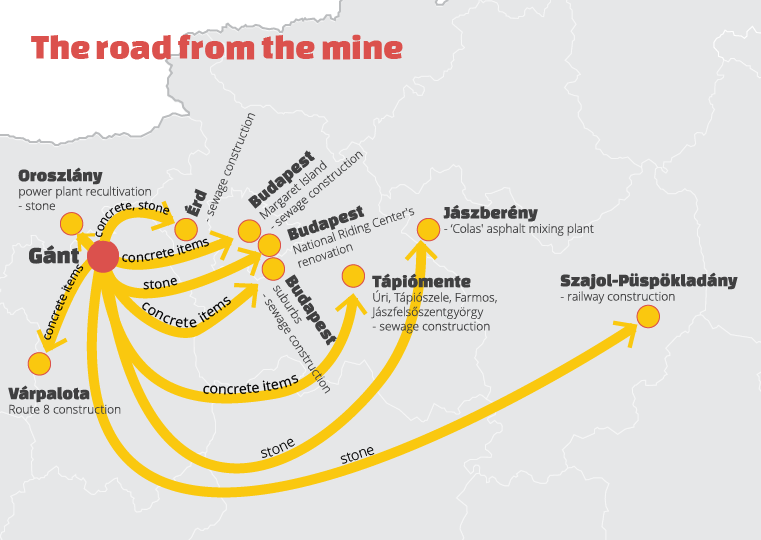

During the privatization process that followed the collapse of the socialist system in Hungary, in 1992 Győző Orbán and his business partners managed to get hands on a company operating the mine in Gánt. The purchase was helped by companies with ties to the Fidesz party, an article entitled “Boys in the mine” revealed in 1999. According to the article, a company linked to Simicska, previously capitalized from the party’s money, bought a share in the mine company during the privatization, then sold it well below its nominal value to Orbán’s father and his business partners.

Thus, Győző Orbán became the majority owner of the company called Dolomit Kőbányászati Kft. (Dolomit Rock Mining Ltd.). Győző Orbán later established other companies with his two other sons, Győző Jr. and Áron, but based on its revenues and activities, Dolomit is still playing a central role in the family business.

After this episode in the early 90s, Simicska did not appear to play any role in the Orbán family’s business activities. He focused on helping his high-school friend Viktor Orbán to transform Fidesz, a small liberal party at the fall of communism, into a major political party. From the outside, there seemed to be a clear division between their responsibilities: Orbán was fighting on the political frontline while Simicska was working behind the scenes to provide a solid financial background for Fidesz by acquiring companies that later won state tenders from Fidesz-led municipalities. He apparently used some of that money to build a media empire that supported the party.

In reality, however, the division was not so stark.

Orbán’s men

Simicska, according to sources close to him, frequently talked with Orbán, and the businessman’s inner circles also included people who were close to the politician. The most prominent among them was Zsolt Nyerges, a lawyer, who joined Simicska as an associate in the mid 2000s. They worked closely together on further strengthening Fidesz’s economic background, with Simicska taking care of the strategy and Nyerges running the daily operations.

According to a friend of Simicska, it was not the businessman who chose Nyerges, but accepted him at the request of Orbán. “Nyerges was a friend of the Orbán family,” said the source, adding that Nyerges was sent to Simicska so that Orbán had a confidant in the businessman’s circles.

The Orbán companies’ involvement in state projects in recent years. Source: Direkt36, Figyelő, Magyar Narancs

Later there were other overlaps between Simicska’s business empire and Orbán’s personal circle. In May 2010, a company linked to Simicska became the majority owner of an energy company called ES Holding, whose co-owner and director was the then-24-year-old István Tiborcz. At that time, the young man was already dating his future wife, Ráhel Orbán, Viktor Orbán’s oldest child. Tiborcz kept serving as one of the directors of the energy company, but continued his business activities under the supervision of Simicska and his associates.

During this period, Simicska’s empire – including its flagship company, construction giant Közgép – produced spectacular growth. The firms kept winning lucrative state tenders, while government positions overseeing major construction projects were also filled with people close to Simicska and Nyerges. This turned Simicska and his companies into a frequent target of opposition politicians and anti-corruption activists, who said that the businessman’s empire symbolizes the rampant corruption of Orbán’s government.

“There was a ceiling”

While the revenue of Simicska’s companies multiplied in just a few years, the performance of the Orbán family’s businesses largely stayed on the level they had been in 2010 and before. This happened despite that Simicska’s companies could have easily given them plenty of work in the state-financed projects they were in charge of.

Not doing so was the result of a conscious decision, according to construction industry sources familiar with the details. “Lajos [Simicska] limited the opportunities of the daddy [of Orbán] in several ways,” said one of the sources, the owner of a construction firm that had worked closely with Közgép. One of Simicska’s close associates also confirmed this to Direkt36. “There was a ceiling for the Orbán family. They could go as high as that, but could not get more,” the associate said.

The associate said that this was not Simicska’s own decision, he just followed Orbán’s directions. The source could not tell whether Orbán made this request personally, but he said that it was clear that it originated from him.

Limiting the family businesses’ involvement in public projects could have been important for Orbán so that he can avoid what happened under his first term as prime minister between 1998 and 2002. At that time, he was often criticized because of his father’s businesses. Opposition politicians have brought up that Dolomit Ltd. was a supplier of the then state-owned Dunaferr, and some also alleged that the company supplied materials for state-funded motorway constructions. With regards to Dunaferr, Orbán’s family emphasised that Dolomit Ltd. had already become its supplier in 1997, before the first election victory of Fidesz. They denied, however, the involvement of the father’s business in the motorway projects.

In a TV interview in August 2001, Orbán tried to refute the accusations arguing that if he had really wanted to favor his father, he would have not only helped him to get orders worth of some tens of millions of forints, but he would have been able to aid him build the whole motorway. Orbán also stated that his father had planned to get involved in certain motorway constructions, but dropped these plans at his son’s request. “This was a very difficult conversation, by the way. He did not agree with this, but eventually he said that there must be certain correlations that I see better than him, and then he accepted it,” Orbán said.

Unsatisfied relatives

Orbán’s family did not seem to take the restrictions well after 2010 either. Sources working in state-financed projects and close to Simicska, told Direkt36 that the prime minister’s family expressed their concern to Közgép’s management over the limited amount of work they got from the company. As Direkt36 showed in a previous story, Közgép ordered products from Dolomit Kft. in certain sewage constructions, but the family wanted to get more, sources said.

It was not only Orbán’s father and brothers in the prime minister’s family who had conflicts with Simicska. István Tiborcz also had a tense relationship with the leaders of the Közgép group. The management thought that the young businessman was acting too independently in the matters of E-OS, the energy company Közgép had bought a few years earlier. “There was a conflict because of the different business approaches,” said one of Simicska’s associates. He added that Tiborcz is an intelligent person, but he did not understand that “first he should have learned how things work on a lower level.”

Lőrinc Mészáros, a longtime friend Orbán and mayor of the prime minister’s hometown, was also frustrated by the volume of orders he received from Simicska’s circles. In the early 2010s, Mészáros, a former gas repairman who later founded a construction company, complained to other people in the industry about the contracts he could get in state projects. “He said that Lajos [Simicska] is bleeding him out,” recalled a contractor who had worked with Mészáros.

The pushback against Mészáros was not done at Orbán’s request. It happened simply because Simicska’s companies were not happy with the performance of Mészáros’ firm. A top manager at Közgép told a contractor that “Lőrinc cannot be let close to the constructions because his company doesn’t work well.” A source close to Simicska added that Mészáros “wanted to work at a very high price,” so the Közgép group was only willing to give him smaller contracts.

Signs of change

The situation, however, started to change in the favor of those who were frustrated by Simicska’s influence. In 2013, there were signs that the businessman’s position began to weaken. Duna Aszfalt, another construction company, which teamed up with Lőrinc Mészáros, emerged as a rival of Közgép. A few months before the 2013 September wedding of Ráhel Orbán and István Tiborcz, Közgép quit the energy company managed by Tiborcz.

The personal relationship between Simicska and Orbán also started to get cooler. “In 2013, it was clear that the set-up was changing,” a close friend of Simicska said. According to the source, Simicska learned that Orbán was planning to cut back the influence of the Simicska-controlled media companies within the government-leaning media conglomerate.

After Fidesz’s reelection in April 2014, the conflict became visible for the wider public as well, as figures close to Simicska were purged of government positions. This included Lászlóné Németh, a longtime confidant of Simicska, who was the minister in charge of major construction projects. In early 2015, the conflict turned into a full-out war when Simicska threw slurs at Orbán in response to the prime minister’s alleged interference in his media businesses.

At the same time, the businesses of those personally close to Orbán skyrocketed.

The companies of Orbán’s father and brothers have nearly doubled their revenues since 2013 and their profits have risen even faster. While in 2013 they gained only 15% of profit on their total revenue of 2.7 billion forints (8.6 million euros), their profit increased to 30% on 5.2 billion forints (16.7 million euros) of revenue by 2015. The profit gained during these three years was fully withdrawn from the companies. In 2016, the revenue was significantly lower (11.3 million euros) but this was an industry-wide trend, most probably because of the sudden slowdown in EU-financed construction projects. (The slowdown was only temporary, new projects have been launched since then.)

István Tiborcz’s energy company produced similarly large growth after Simicska and Tiborcz parted ways. In early 2014, Tiborcz regained his ownership in the company then called Elios Innovatív, which began to win a series of lucrative state tenders for upgrading street lighting systems in several cities. Elios got the majority of these tenders without facing competition. (As Direkt36 revealed it earlier, this happened because the tenders’ conditions were tailored to Tiborcz’s company.)

Lőrinc Mészáros’ rise was the most spectacular. In only a few years, the former gas repairman has become one of the country’s wealthiest person, now holding major positions not only in the construction business but also in the media sector, tourism, and the bank industry. As Direkt36 showed in a recent article, a rail construction company linked to Mészáros even took over a firm that had been part of Simicska’s empire.

Hidden works

Compared to Mészáros, the Orbán family’s enrichment has been more modest. In 2015, István Tiborcz even sold his shares in Elios Innovatív after the controversy surrounding the company’s state tenders grew bigger and drew the attention of Hungarian and European Union authorities. Since then, Tiborcz personally has stayed away from state businesses, but people close to him remained involved in them.

The companies of Orbán’s father and brothers are still working on state-financed projects but it is hard to get information on them as they are hired not directly by state agencies but by contractors or subcontractors. In Hungary, the public procurement database contains information only about the contractors and major subcontractors but there are no records available about those who work on the lower levels.

Direkt36 managed to unearth details about some of the Orbán family’s contracts through a months-long investigation. It is still not known how much money their companies got for these works as the records obtained by Direkt36 did not contain information about the payments and the Orbán companies never responded to any of our inquiries.

Apparently, it does not bother Viktor Orbán anymore that his family members are involved in publicly funded projects. At a press conference in June, Orbán told Direkt36 that he still considers it important for his father not to participate in public investments. Orban’s answers, at the same time, also suggested that he thinks – as opposed to his earlier statements – that if his father does not participate in the project as a main- or subcontractor but as their supplier, it is not problematic. He said this in spite of the fact that suppliers also receive public money, just like higher level participants of state projects.

For company records, we used the services of Opten.