“We just spread the bacteria all over the hospital” – Why is the prevalence of dangerous hospital-acquired infections growing in Hungary?

A 35-year-old woman with a degree in geology gave birth to her son by Cesarean section in October 2021 at a university clinic in a big city. After the operation, she fell while showering, which caused her wound to tear under the suture. As it was not visible externally, she was sent home from the hospital. At home, however, she got worse and became delirious due to the fever, so a week later she was taken back to the clinic by ambulance, where she underwent surgery to treat the haematoma. Initially she was admitted to intensive care and then to the Covid ward, as she was diagnosed with a coronavirus infection.

That was when something happened that led to even more trouble for her. She was given a diaper that had overlapped with the fresh surgical wound on her abdomen. The woman said that at times she had not been cleaned for several hours, and that her wound eventually became infected by the enterococcus faecalis bacteria in her own faeces. However, this was only discovered later.

“I understand that the nurses are overworked, however, I had to beg the nurse on duty for hours to clean me up. She kept telling me that she would do it later,” she recalled.

The recovering mother was receiving treatment at the gynaecology clinic when the lab results confirming the infection arrived. “The doctors said it was probably due to the diaper.” After that, her wound healed slowly, but the most difficult aspect for the woman was not being able to spend the first month of her newborn’s life with him due to the hospital treatments.

The young mother shared her hospital records with us, which confirmed her account. However, she asked us not to write down the name of the institution or contact them, as she still goes back there for treatment and does not want to suffer any disadvantage.

The woman and her husband considered legal action and also contacted a patient advocate, but in the end, they felt they had no energy to pursue a lawsuit. Hospital malpractice lawsuits involving hospital-acquired infections are certainly rare in Hungary, although there are examples of patients winning lawsuits against hospitals. Péter Szűcs, a Budapest-based attorney specializing in malpractice cases, took a particularly tragic case in the 2010s involving two women who became infected in 2008 at the Bács-Kiskun County Hospital while lying next to each other in the same ward.

One of the women who had undergone spinal surgery recalled her memories of her hospital stay to Direkt36 but asked not to have her name mentioned. She had the operation a decade and a half ago, in 2008, when she was 50 years old. She will never fully recover.

She and her elderly roommate, once working as an accountant, were both infected with MRSA (short for “methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus”), a superbug that is very difficult to kill as it is resistant to many antibiotic treatments. It proliferates in wound exudate, among other things, and greatly impairs the condition of sickly patients, complicating their recovery and even leading to life-threatening conditions. If, for example, it enters the bloodstream and causes blood poisoning, also known as sepsis, it can rapidly infect and shut down the patient’s organs and progressively reduce their chance of survival in severe cases.

The confident, friendly woman, now on a disability pension, lives with her husband in a family house surrounded by cucumber plantations and farmland on the outskirts of Nagykőrös. Sitting next to a flower vase on her kitchen table, a plate of apricot jam-filled linzer, and a stack of medical papers, she described how she takes several handfuls of medication a month, from cardiovascular remedies to anti-inflammatories and painkillers. Due to what happened at the hospital, her right leg is now five centimeters shorter than the other, the veins in her shin are ruined, her skin is dark purple and swollen, and no cream relieves the constant burning sensation.

“I can only limp with two crutches, I can’t stand long enough to peel an onion,” she said.

The court ruling reveals what happened to her. After the first surgery, her wound did not heal, it kept discharging drainage. She was treated with an antibiotic that is not effective against MRSA, so it continued to spread in her body. In total, her wound had to be reopened and operated on four times before she ended up in the emergency room, also suffering from severe pain in her hip at this point. It turned out that the whole area was severely infected, and the head of the femur was “incomplete and friable”, according to the court’s verdict. This was followed by further unsuccessful therapy, and she repeatedly visited the hospital for a total of three years.

At first, the woman asked the nurses hopefully if her wound was healing. “A tiny bit,” the nurse said, according to the woman. But the situation had not improved.

“I had pus constantly flowing from my wound, sometimes it was the size of a goose egg, and my drains were full. A nurse came in and I told them what was wrong to which they replied: ‘we’ll be back’. They came several hours later, by that time there was pus all over the floor, dripping there” she said.

The woman was not told at the hospital what MRSA infection was, or why she was going back into surgery. “It’s all right, lady”, “it’s just wound discharge, lady”, the doctor reassured her month after month, said the woman. She had become debilitated, suffering for the third year, when they consulted a private doctor in Budapest who specialized in wound treatment. According to the woman, they cured her of the infection in a month.

After many years of litigation, the court awarded her damages and an allowance, but there were no other consequences. Neither the doctors nor the hospital have apologized, and as far as she is aware, all the doctors who treated her are still in their posts.

Bács-Kiskun County Teaching Hospital has not replied to Direkt36’s request for comment.

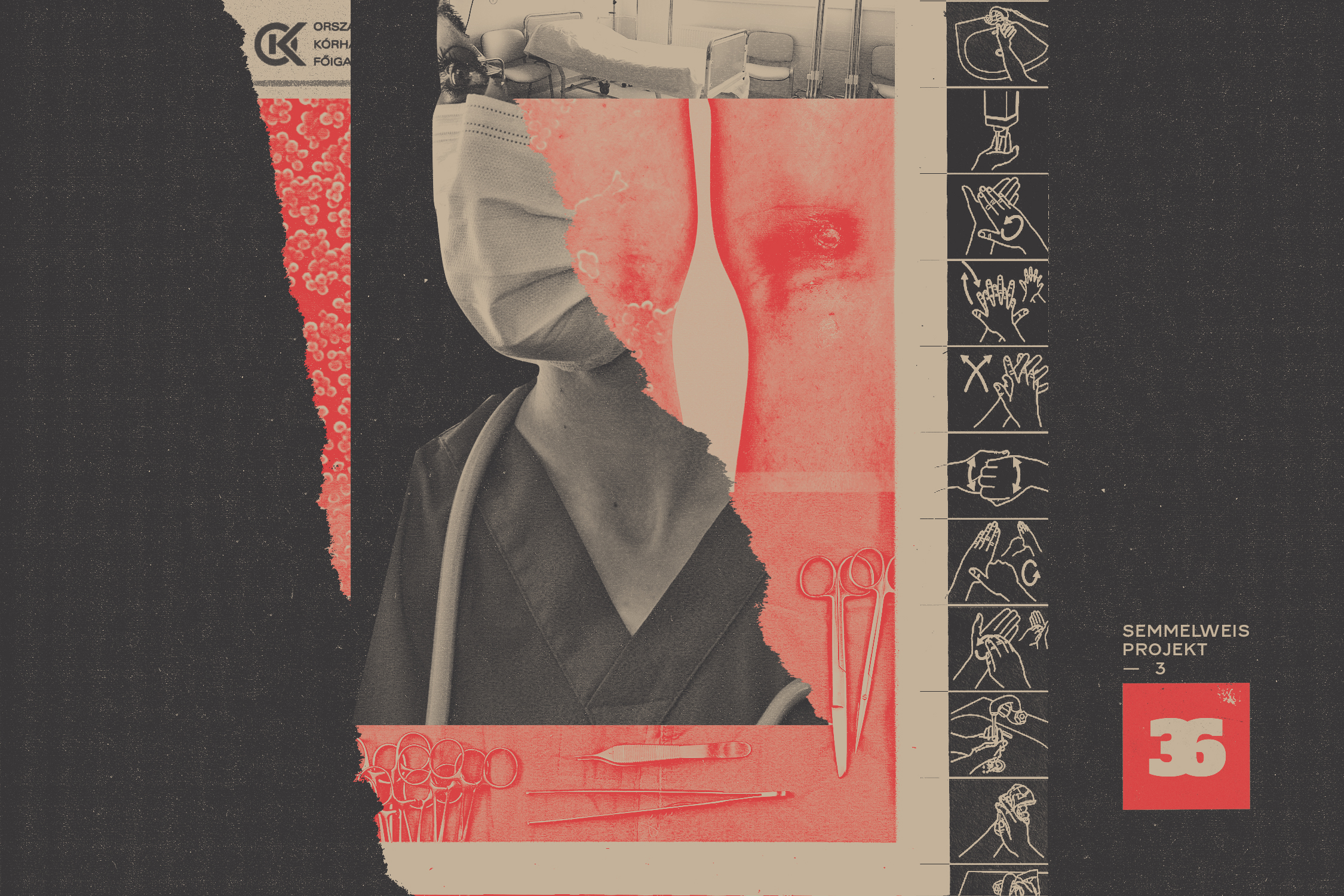

Dying of sepsis in Semmelweis’s homeland

We have collected more than half a dozen similar stories of misery from hospitals across the country (we will show more of them in our film, to be released on 11 November). In all cases, additional time spent in the hospital and the pain of recovery could have been avoided if patients had not encountered dangerous pathogens within hospital walls.

Over the past decade, the incidence of hospital-acquired infections has steadily increased by almost all indicators, with more cases of multidrug-resistant infections, clostridial infections, and bloodstream infections – as we have reported in the previous articles of this series.

Hospitals are not to blame for some of the reasons: there are more and more elderly, debilitated, seriously ill patients with a range of underlying conditions who are more at risk of contracting infections than healthy people. Sometimes they themselves bring pathogens in, and visitors also aren’t as careful about hygiene as they should be. Meanwhile, bacteria worldwide are becoming increasingly resistant to antibiotics given in abundance in hospitals. In intensive care units, patients have tubes sticking out of their bodies, and any invasive procedure risks something entering their system and making them even sicker.

But there are also several factors that depend on hospitals and their staff. Dr Zsolt Hegedűs, an orthopedic specialist who is also a member of the Hungarian Medical Chamber and who often speaks publicly about the importance of combating infections in hospitals, has a low opinion of the quality of infection control in Hungary.

“Although hand hygiene has probably improved due to Covid, we are still not doing enough in the home of Ignác Semmelweis to protect our patients from infections by simply washing hands,” he said.

“Today there are no consequences to multiple septic complications being linked to a specific doctor in the department. It is a disgrace that so many people die of sepsis in Hungary. And it is a terrible death” he added. According to the specialist, human lives depend on how seriously the healthcare system takes infection prevention. Also, treating infected people costs hundreds of millions of forints, money that could be saved. “And all this is being swept under the carpet in Hungary. It is a shame and a disgrace” the doctor said.

Everyone must work together

In the first part of our series, we explained how politicians are trying to hide the problem rather than find a solution, and in the second part, we described how we obtained and analyzed data to assess the performance of Hungarian hospitals. But to understand what combination of problems at the hospital level is causing the situation to worsen rather than improve, we have also conducted dozens of interviews and background discussions with health workers – nurses, cleaners, doctors, hygienists (formally known as infection control specialists) and hospital managers – over the past months.

This has often not been easy, as since the Minister of the Interior is responsible for the health sector, public speech has been even more restricted than before. Hospitals cannot even think of making statements to the press without permission from the National Directorate General for Hospitals (NDGH). As we asked about a sensitive issue, many people either gave information asking for anonymity or refused to meet altogether. Their reasons for refusal varied: some said they would be gambling with their jobs as civil servants or that they had no knowledge of infections, others did not want to talk because they were retired or in other cases because they were not yet retired. There was even a hospital worker who stated that “it would not be ethical to talk about their former job”.

Yet there were many who spoke, even if on the condition of anonymity, about the cluster of problems that play a role in the spread of infections. Among them were professionals with decades of experience who take infection control very seriously. For example, a doctor of hygiene in a large provincial hospital, according to whom infection control in a hospital only works well if there is someone to coordinate it, while at the same time, the whole staff is needed to make infection prevention really work.

“It’s not basic everywhere, but we do regular environmental bacteriology tests in operating and intensive care units. We take samples from the hands of staff members to check the effectiveness of hand disinfection and we also check scrubbing” he said.

His experience is that workers look forward to the results because they welcome the feedback. “And if the results are not good, we don’t tell their boss straight away, instead we give them advice on how they could improve,” he said.

There is no time for handwashing in the daily rush

According to most health workers we interviewed, there are very few positive examples in the country. The middle manager of a large hospital in Budapest said that enthusiastic professionals are everywhere and that the situation is good “on paper”: there are procedures, strategies, policies, and training for staff in infection control, as required. The sterilizers are functioning, and the washing of bed linen and cleaning is also done one way or another. The problem, he says, is not this, but that despite all efforts, the constant focus on infection prevention, the basic principle of proper disinfection, “is still not part of the work culture in hospitals”. With the end of the coronavirus epidemic, he says, “the fear of infection has disappeared” and once again hand sanitizer dispensers are not always refilled.

Due to the constant lack of resources, hospital management is usually preoccupied with day-to-day operational problems: ensuring that there are enough people, adequate salaries, medicines, and resources. It is a daily struggle, according to the hospital’s middle manager, to “have enough footbags, disinfectants, rubber gloves, paper towels” and to make sure that the constantly rotating, severely overworked staff can wash their hands between working with different patients. In the wards, they do what is mandatory, they report the infections, but their energies are spent on day-to-day functioning” the source said, referring mainly to the very heavily overloaded hospitals in Budapest, which are struggling with masses of patients and have the most dilapidated infrastructure.

The devastating effects of staff shortages have been highlighted by several hospital nurses. One source, who has more than 20 years of experience as a nurse in a public hospital, reported that the high number of resignations resulted in so much extra work that nurses often had to do the work of doctors and cleaners as well.

“When three people use the nurse call at the same time because they are unwell, I can’t follow all the hygiene rules even if I want to,” they said.

The hospital’s hygiene department has not been conscientious in its inspections either, they said: it sometimes neglects to conduct infection control trainings for years, or even gives advance notice of when it will come to carry out an inspection, so that “everyone can clean their department on time and produce good results.”

Besides being overworked, negligence can also be the root of the problem. A doctor who used to work at a large university clinic sees it as a sign of indiscipline, for example, that hospital workers are often seen walking near hospitals in white uniforms, and therefore wearing their work clothes out on the streets. They also believe that the realities of Hungarian hospitals play the biggest role in the shortcomings: 6-8 bed wards, dozens of patients per nurse. “There would be no skin left on a nurse’s hands if they always washed their hands with soap before and after seeing each of 30 patients,” they said. “Not even the head physician goes to wash their hands before and after every patient during a ward round. Yet this is what works: single wards, constant disinfection, protective equipment” they explained.

Beáta Dunavölgyi, who now works as a hospital nurse in Austria, but previously worked in two Budapest hospitals for years, also described deplorable conditions.

“I often saw the doctor examining a patient without gloves, then moving on to the next patient without disinfecting their hands, and touching the catheter or probe in the same way” she recalled.

She also noticed that when a hospital-acquired infection occurred, they rarely investigated why it happened, and just isolated the patient with a privacy screen. “Not by placing the patient in another room, but with a screen. We are supposed to be suited up at such an occasion, but in practice, we put on a kind of apron and a mask” said the nurse, who herself was once infected with MRSA and presumably contracted the infection from one of the patients. She has not seen anyone – doctors, cleaners – reprimanded for infections spreading in their ward.

Further damaging the chances in the fight against infections is the fact that, despite being mandated by decree, many hospitals cannot hire enough hygienists as there are simply not enough applicants, due to low pay and a lack of interest in the field. “Training in epidemiological care was ended years ago, infection control is not a compulsory subject in medical education, and there is hardly any practical training. Only at Semmelweis University is there any serious infection control training. The age graph of hygienists is disastrous” an infection control specialist listed the problems.

The availability of microbiology laboratories is also a big issue, with smaller institutions not having their own labs and blood and stool samples sometimes having to travel many kilometres. Moreover, laboratory tests are not cheap and are a burden on hospital budgets. The hygienist of a large provincial hospital recalled that they once received a call from a small hospital asking for their advice because several of their patients had wound infections. The hygienist asked what the lab test had revealed and it turned out that no samples had been taken yet. However, suspected infections and epidemics cannot be detected without laboratory tests.

Take a look at the hospital’s toilets

The serious problems with hospital cleaning came up very often in our interviews. Just as the immaculate cleanliness of health workers’ hands, the quality of cleaning is also an important factor in preventing infections and epidemics.

“If you go into a hospital, go into the public toilets and see if there is soap, hand towels, hand sanitizer, and if it is clean. If not, turn around and walk out. In the same way as a restaurant toilet is a measure of general cleanliness,” said Dr Zsolt Hegedűs.

Beáta Dunavölgyi stated about a hospital in Budapest, where she used to work as a nurse, that elderly and overworked cleaners were responsible for maintaining a clean environment. “Poor Mária was pushing the cart at the age of 84 and even helped to serve food, it was a disaster. There were other cleaners like that, well, they clowned around like that.”

A young woman, now an assistant nurse but formerly a cleaner for many years, spoke of feeling exploited in a large Budapest hospital, where there were few cleaners anyway. Her highest salary was 196,000 forints for working 12 hours a day, with a total of 4 days off that month. On several occasions, she worked 14 days in a row. For a decent job, she said several times the number of cleaners would have been needed. In addition, she added, cleaning in a hospital requires neither qualifications nor experience, with one cleaner training the other. But to disinfect professionally, one needs to know several hygiene rules, and when there is an infectious patient in a room, the cleaning must be done differently, she explained. “Otherwise we’ll just spread the bacteria all over the hospital,” said the assistant nurse formerly working as a cleaner.

“Cleaners are mostly grossly underpaid, undereducated people who are not properly trained, don’t always understand the process of precise surface disinfection and why it is important,”

a hospital middle manager echoed the former cleaner’s experience. Cleaning is mostly outsourced by hospitals, the quality of which is monitored by nurses, hygienists, or care managers, who in most cases simply go around and have a look. “Outsourcing caused even more problems during Covid when a significant number of cleaners refused to clean the Covid wards out of fear of the epidemic. Therefore, volunteers often did the cleaning” recalled the middle manager of a hospital.

In addition, cleaners in hospitals use a range of outdated technologies. They “drown everything in chemicals”, paradoxically helping the most resistant pathogens to survive, explained Tibor Ritz, a specialist in hospital cleaning. Rules for hospital cleaning in Hungary were last established in a 2012 document. This recommendation, known as the “yellow book”, is now outdated and is not even available online, only in antique shops at best, he added.

But the biggest problem, as in many areas of healthcare, is the lack of funds. Hospitals’ budgets are so tight that the management usually tries to save as much as possible on cleaning as well. This was one of the points made to Direkt36 by a source who used to be a manager in hospital cleaning. “The cheaper option always wins” – according to him, this is in fact the only criterion used in the cleaning tenders put out by hospitals.

“Sometimes you get the feeling that hospitals want a Mercedes at the price of a Trabant,”

explained the source, adding that in such circumstances companies save money wherever they can: on wages, equipment, and cleaning products. According to the man formerly working for a cleaning company, the attitude of hospitals has not changed since Covid, the prestige of cleaning has not increased, and it is rare to find a hospital where the hygienists see the cleaning team as partners.

However, it would make sense to spend more on cleaning. A hygienist at the Szent Rafael Hospital in Zala County once calculated how much money a hospital could save by improving hygiene conditions and thus avoiding the treatment of costly hospital-acquired infections. Edit Kalamár-Birinyi declined to comment for this article, but her 2017 presentation on the topic is available online. It reveals that the hospital had several outbreaks in 2015, but none in 2016, after it managed to greatly improve the efficiency of disinfection cleaning through vigilance and a series of inspections. The number of infectious diseases has dropped from one year to the next.

The hospital hygienist calculated how much the internal outbreaks in 2015 cost the hospital. The treatment of a clostridium difficile outbreak that affected 6 patients resulted in an additional expense of almost 38 million forints to the hospital (due to laboratory tests, medicines, longer hospital stays). An outbreak of MACI, a pathogen that causes sepsis as well as pneumonia, affected 8 patients and cost the hospital almost 43 million forints, which means that the treatment of the two outbreaks amounted to more than 80 million forints.

In contrast, the average market price of quality hospital cleaning was 460 HUF per square meter per month, compared to the 340 HUF average price of inadequate cleaning services negotiated in tenders. Over a year, quality cleaning services cost 76 million forints more than cheap cleaning services, when calculated over the area of St. Rafael Hospital. On this basis, quality cleaning is clearly more worthwhile financially than having to deal with a series of infections and epidemics due to poor hygiene in hospitals, the hygienist concluded. Not to mention the increased confidence and satisfaction of uninfected patients, the savings of sick pay to the state and the suffering avoided.

They understand the problem in the management as well

In fact, the obstacles to the prevention of hospital-acquired infections are well known to the health authorities. Cecília Müller, the national chief medical officer, also spoke to a medical publication in 2019 about the problems with cleaning and the dangers of using antibiotics too often.

Beatrix Oroszi, an epidemiologist and acting director of the Centre for Epidemiology and Surveillance at Semmelweis University, also gave a presentation on hospital-acquired infections in 2019, which is also available online. In it, she not only stressed that “healthcare-associated infections are one of the biggest patient safety risks today” and that 30-50% of infections could be prevented but also provided a SWOT analysis of infection control in Hungary. Among the weaknesses she listed the shortage of health workers and infection control specialists. Among the threats, she mentioned new pathogens, an increasingly vulnerable patient population, the emigration of professionals and the low capacity of microbiology laboratories.

The problem is further amplified by the lack of cooperation between the agencies responsible for running the institutions and the ones responsible for controlling hospital-acquired infections. While the data on hospital-acquired infections are received by the National Centre for Public Health and Pharmacy (NCPHP), compliance with their rules is monitored by the county government offices, and the funding of hospitals is managed by the National Directorate General for Hospitals.

Dr. Ágnes Galgóczi, Head of the NCPHP’s Hospital Hygiene and Regulatory Division, did not say in an interview with Direkt36 whether they keep track of which hospitals have the highest incidence of hospital-acquired infections. According to her, it is the responsibility of the hospitals and the county government offices to assess the situation regarding hospital-acquired infections in each institution. In practice, this means that each hospital should have an institutional infection control and antibiotic committee that oversees infection control activities and aims to reduce the number of infections in the hospital. This committee issues reports on the developments concerning hospital-acquired infections in their institution and sends them to the county government office. Furthermore, the county government offices monitor the work of the committee.

“The counties, if they see that there is a problem, can decide how often they meet with the committees to consult,” Galgóczi said. “We cooperate with the NDGH, and the NCPHP also describes the reasons for the increase in infection rates to the government (…) But the decision-making is beyond our control.”

In the first part of our series of articles, we presented how official agencies try to hide data on infections, and in the second part, we published a ranking of hospitals by the incidence of hospital-acquired infections. In the final part, we will demonstrate how other countries have succeeded in reducing hospital-acquired infections and what role open communication has played in achieving that.

To follow further articles in this series, sign up to receive alerts on our investigations.