Benjamin Netanyahu was smoking one cigar after another while self-confidently explaining to Viktor Orban how he would return to power and make peace with the Palestinians. Orban met him in a private room of Jerusalem’s iconic building, the King David Hotel, in June 2005 on the third day of his four-day trip to Israel. Netanyahu, often called by his nickname Bibi, also spoke about how to fix a country’s economy, and Orban listened sometimes in disbelief, sometimes in admiration.

Netanyahu’s first premiership in Israel lasted from 1996 to 1999, but at the time of his meeting with Orban, he was relegated to serve as Minister of Finance. Direkt36 reconstructed their 45 minutes meeting with the help of several sources. The two politicians immediately had a connection. Orban later explained that there was a common emotional note, because at that time they had both been forced out of power. According to Peter Breuer, who helped Orban as an interpreter during his trip,

“Orban and Netanyahu loved each other.”

Orban returned to Hungary with determinative experiences. Basically, this trip has resulted in him developing close ties and a political alliance with Netanyahu. This relationship has since changed the foreign policy doctrine of his party, Fidesz, which used to balance relations between the Arab world and the Jewish state, but gradually became a staunch supporter of Israel. The alliance of Orban and Netanyahu has opened a new chapter in the relationship between the Hungarian right and the Jews, but it also changed internal power relations inside the Hungarian Jewish community. What is probably the most important to Orban, is that this relationship has opened doors for him to the United States after a decade of alienation.

On September 17, 2019, early elections were held in Israel, resulting in a stalemate with no convincing majority for either the right, or the left-wing coalition. This could easily mean the end of Netanyahu’s more than 13-year-long premiership. Direkt36 tells the story of how the Hungarian and Israeli right slowly found each other through the relationship of Orban and Netanyahu. We have spoken to more than two dozen sources for this article in Budapest and Washington DC representing Hungarian, Israeli, American and EU countries. Many of them only agreed to talk on condition of anonymity.

THE STAMP OF ANTI-SEMITISM

Maariv, the right-wing Israeli daily newspaper published a long interview with Viktor Orban, the youngest prime minister in Central Eastern Europe, a few months after his 1998 election victory. This interview was the introduction of the ambitious and charismatic Orban to the Israeli public. He was pleased with the result. “Our job is to be friends with Israel,” Orban told his staff at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. However, Orban’s first government soon faced criticism.

Relations with the Jewish community became part of domestic political debates even during the time of the regime change. Geza Jeszenszky served as Minister of Foreign Affairs in Jozsef Antall’s government from 1990. He recalled several episodes when their political opponents had repeatedly raised the issue of antisemitism within MDF (Antall’s center-right political party) during trips to the United States before the 1990 election. According to Jeszenszky, “American press, especially The New York Times, were the main vehicle of the anti-MDF campaign.” After the MDF government was ousted in 1994, Viktor Orban sensed an opening in the political space and shifted his party, the liberal Fidesz to the right. Many of the then-known anti-Semitic figures of the Hungarian right joined his political camp. After their election victory in 1998, the shadow of anti-Semitism was cast over Fidesz. Israeli Ambassador Judith Varnai Shorer and U.S. Ambassador Nancy Brinker repeatedly called out anti-Semitism, which sometimes appeared within the Fidesz camp.

The main problem was with Istvan Csurka and his far-right party, MIEP. Csurka had been expelled from MDF and then he created his own party, which was openly advocating its extremist and anti-Semitic views. Prior to the 2002 elections, several articles in the U.S. press predicted a likely alliance between Fidesz and MIEP. Janos Martonyi, who was Minister of Foreign Affairs at that time, and others too had told the Israeli and the U.S. Ambassador that as a matter of principle, Fidesz would never enter into an alliance with Csurka. “But we couldn’t really talk about this publicly as we didn’t want to alienate the voters of MIEP”, a diplomat of the first Orban government said.

The criticism that Orban and Fidesz received because of their unclear relationship with MIEP and anti-Semitism were very damaging to their international reputation. This was despite the fact that none of the sources for this article, not even his critics have called Orban an anti-Semite during on background conversations. “Orban mostly resembles (former Socialist Prime Minister) Gyula Horn in this case. Horn also didn’t like the liberal Jewish intellectuals. However, neither of them was a visceral anti-Semite, while in fact there were many anti-Semitic turds in their parties,” said Andras Simonyi, a former diplomat who worked on establishing diplomatic relations with Israel before 1989, and later became ambassador to NATO and the United States.

“Tactical anti-Semitism” is the label Simonyi used describing Orban’s “very reprehensible” attempts to seduce MIEP voters, which has caused much more and lasting damage to Orban’s reputation in the United States than in Israel. “Primarily but not exclusively, the liberal Hungarian Jewish intellectuals were attacking him with anti-Semitism as a political weapon. But at the same time, these intellectuals did not show much solidarity with Jews living in Israel,” Simonyi said, referring to the typically Israel-critical attitude of Orban’s left-wing critics.

Orban lost re-election in 2002. Learning from his defeat and the fact that anti-Semitism had become a campaign topic, Fidesz’s leadership decided in the fall of 2004 that, as part of the preparations for the next election, Orban must personally visit Israel. At that time, the center-right Likud was governing Israel. Orban named Likud as natural ideological partner of Fidesz when the Israeli Foreign Minister visited Hungary in the spring of 2005. A few months later in June 2005, Orban arrived to Israel as leader of the Hungarian opposition. That was the trip on which he met Netanyahu and which has changed his attitude towards Israel and the Jews forever.

At first, however, it was difficult to persuade him to take the trip, as his memory of the 2002 election was still too vivid. Orban’s defeat in 2002 was very narrow, accusations of anti-Semitism stuck to Fidesz and were exploited by his political opponents.

“He was not enthusiastic at all, absolutely not. It must have been hard to push this visit down his throat. At the time, he was still a badly affronted man who felt that he had been betrayed by the liberal elite with Jewish background in 2002”

a former diplomat serving in Tel Aviv recalled how much effort it had taken to make the journey happen.

One of the masterminds behind the trip was former Ambassador Janos Hovari, a member of MDF’s old foreign policy bureaucracy. He was appointed by Orban to Tel Aviv in 2000, and despite the change of government, Hovari was still helping Fidesz. “Fidesz had no interest in Israel, it was more of a necessity for us to win the next election somehow. Janos pushed for this relationship between Fidesz and Likud, because he thought this was the way to make [Orban] acceptable,” said a former diplomat to Tel Aviv. “It was just a bonus that it turned out that Orban and Netanyahu were like-minded.”

THE OTHER ISRAEL

Viktor Orban in Jerusalem in 2018. Photo:kormany.hu

Israel had a great influence on Viktor Orban even during his very first trip in 2005. Inmediately upon arrival, he was “very positive and interested. In addition, he is one of the Hungarian politicians who knows the New and Old Testament very well. The moment he started walking the Stations of the Cross, the Via Dolorosa, he knew everything,” Peter Breuer, who accompanied the delegation at the time, told Hungarian weekly Hetek. Ha also recalled to Direkt36 how Orban walked through the Old City of Jerusalem together with a tour guide and Hovari, identifying biblical locations almost stone by stone.

In addition to the Holy Land and spiritual experiences, “Orban liked the people the most, the straightforwardness of the Israelis and the sincerity of his counterparts,” Breuer added. “I had the impression that the Hungarian Prime Minister was always first and foremost interested in how Israel works as a proud nation state, one that is extremely strong despite the threats that surround it” said Rabbi Slomo Koves of the Unified Hungarian Jewish Congregation (EMIH), who maintains close ties with the government. 13 years later, in 2018, Orban traveled to Israel again and visited the Western Wall. A Hungarian Jew from Transylvania came up to him and asked what it was like to be in Israel. “It feels good to be in a country where people can proudly be themselves”, Orban replied, according to a source who was present.

Israel also impressed Orban politically on his first visit, and he was truly surprised by how well-developed, well-functioning the country had become. “Israel was far from an organized state at the turn of the 80s, 90s, but Netanyahu and Likud eventually made it into a strong, solid capitalist country,” said a source to whom Orban recalled his first visit years later. Immediately after concluding their first meeting in 2005, Orban praised Netanyahu’s drastic tax cuts and job creation stimulus in an interview with MTI, Hungary’s state news agency.

“In Fidesz circles, it is a popular example of how many similarities there are between the history of the long-oppressed Israeli and Hungarian right, Likud and Fidesz. The parallels also apply to the personal stories of Bibi and Orban”, Slomo Koves told Direkt36. “After decades of total left-wing dominance, the Oslo peace process had completely written off the Israeli right. After many defeats, Bibi nevertheless managed to lead Likud to victory and was able to expand the ppower of the right even in a more polarized political environment than Hungary’s,” the rabbi said.

In 2006, Orban and Netanyahu both lost parliamentary elections, and despite Likud and Fidesz having already talked about each other as sister parties by that time, no real institutional relationship had been established. However, something had radically changed since the early 2000s: Fidesz was no longer receiving attacks because of anti-Semitism, but the exact opposite. “Isn’t that orange in their flag a Jaffa by accident?,” this is how Gabor Vona, chairman of Jobbik, the far-right party replacing MIEP mocked the logo of Fidesz because of the party’s philo-Semitic turn. Besides criticism coming from the outside, not everyone inside the Fidesz-led right-wing community was happy with Fidesz becoming Likud’s sister party.

Besides the impressions Israel made on Orban, the trip has also achieved its political goal. “That ship has sailed when Orban could have been caught red-handed because of his anti-Semitism,” former ambassador Andras Simonyi explained, adding that it doesn’t matter if there are other anti-Semites in and around Fidesz, because nobody else has an international recognition, just Orban. Indeed, Hungarian diplomats name-drop Netanyahu whenever it is needed. For example, a staffer working for a U.S. member of Congress recalled when the current Hungarian Ambassador to Washington D.C. raised this argument at a private event. “We’re not anti-Semites, just look at this nice little photo of Orban and Netanyahu,” the staffer mockingly imitated the scene.

THE COMMON INTEREST

Viktor Orban welcoming Benjamin Netanyahu on his visit to Budapest in 2017. Photo: kormany.hu

Through close ties with Israel, Likud and Netanyahu, Orban not only managed to neutralize the stamp of anti-Semitism, but it also allowed for their relationship to become much more diverse in recent years. With the 2004 expansion of the European Union, the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs saw the new members states as much more pro-Israel than the old Western European member countries. At that time, however, it was not Hungary but the Czech Republic that was spearheading pro-Israel foreign policy, a former Hungarian foreign ministry official recalled. In Hungary before 2010, foreign policy bureaucrats of the governing Socialist Party wanted a balanced approach and to also pay attention to the interests of the Arab states. After Orban’s return to power in 2010, Fidesz’s foreign policy team, led by Janos Martonyi, declared that “we love Israel but this doesn’t mean they can do anything to Palestinians,” a former diplomat of the Orban government summed up their attitude at that time.

The first major rift in Hungarian foreign policy’s traditional balancing between Israeli and Arab interests came with the Arab Spring of 2011. “The leadership of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs believed what the Obama administration was saying, that there was going to be some kind of democratization in the Arab world,” a former foreign ministry official said. Even in the fall of 2011, Janos Martonyi compared events to 1989, but

„Orban was a realist, and he has long said that chaos is coming. And we (in the bureaucracy) were already seeing that the end of the story will not be what Martonyi hoped, but what Orban feared”

the source said.

The Arab Spring also contributed to the transformation of Hungarian foreign policy by sweeping away its old partners, the Arab regimes who were typically enemies of Israel. This has increased Israel’s importance in the region. The country has been once again led by Benjamin Netanyahu since 2009. According to several government sources, the Israelis have helped a lot in interpreting events of the Arab Spring, both for Hungary’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and for Hungary’s foreign intelligence service. “Israel has clearly seen the problematic issues, and many countries have been given the impetus to reassess their relationship with the Israelis,” a former official at the Prime Minister’s Office said.

Tamir Wertzberger, a Budapest-based international relations coordinator for Likud, said that 2015 was the real turning point in the relationship. In Israel, the Netanyahu-led Likud’s huge electoral victory made it possible for the party to finally set up a foreign affairs office and to systematically establish contacts with parties like Fidesz, at an institutional level. It was then that the first official party delegation arrived in Budapest with Wertzberger, Likud’s Director of Foreign Affairs Eli Hazan, a political assistant to Netanyahu and a Likud member of the Knesset.

The other important events in 2015, according to Wertzberger’s explanation, were the refugee crisis and the major terrorist attacks in Europe. From that time on, the Hungarian government began to campaign heavily against migration. International organizations and politicians of EU countries one after another condemned the Hungarian government’s campaign for being anti-Muslim and xenophobic. Likud, however, welcomed the Hungarian government’s action, in which it saw its own views reflected. Wertzberger, Likud’s foreign affairs coordinator, put it: “On the one hand, Europeans are finally beginning to understand Israel, how it is for a Western country to live together with Muslims. On the other hand, migration has created a serious debate between Hungary and the European Union. Israel has long been in conflict with the EU, and when the two countries suddenly found themselves on the same page, it became much easier for Hungary to support Israeli positions.”

Although Hungary and the other Visegrad countries (Slovakia, Czech Republic and Poland) officially recognize the State of Palestine, one of the first consequences of the Hungarian government’s new approach has been the complete abandonment of the Palestinians’ cause, first in the UN and then within the EU. “Ms. Sedin, the Palestinian Ambassador to Hungary, who is by the way Christian, regularly came in to the ministry to protest, and asked why did we have to do this, when we are in good relations with Israel anyway,” a former foreign ministry official recalled. The Hungarian government’s Palestinian policy was soon restricted to help Christian Palestinians.

The policy shift was also accelerated with the retirement of Janos Martonyi and drastic staff reshuffles that followed in the foreign ministry. Under the new leadership of Minister of Foreign Affairs Peter Szijjarto, a completely new approach was taken to the Israeli-Palestinian issue. “The whole shift on Israel and Palestine is just part of the larger ‘realist turn’ in Hungarian foreign policy, which is that there are no values anymore, only short-term interests above all,” a source working for the foreign ministry said. The source recalled that “around 2015, we have barely received comments anymore to pay attention to the Palestinians.”

The shift in the Hungarian government’s policy happened when the Palestinians were starting to receive less and less support from their allies in the Middle East. This tendency was also recognized by policymakers of the Orban government. According to Orban’s recent briefing to his ambassadors, five states are most important in the Middle East: Israel, Turkey, Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Iran. “Orban sees exactly that Turkey loves us no matter what, with Turkish investment pouring in, while the rest do not really care about the Palestinians anymore. Their fate is no longer an important consideration to them” the source working for the foreign ministry added. But, according to the source, the issue is more complex. With its official recognition of the State of Palestine, Hungarian foreign policy is still progressive even among European countries.

The new Israel policy is implemented very consistently by the government. For example, at the end of 2018, when amending a trade agreement between the EU and Jordan, everything that was considered anti-Israel or pro-Palestinian had to be torpedoed, a source working for the foreign ministry recalled. For years, the Common Foreign and Security Policy Department of the Hungarian Ministry of Foreign Affairs has meticulously scrapped from common EU documents anything that they believe Israel would not like. ”What we can do first and foremost for Israel is to dismantle EU foreign policy,” the source explained. This works well in practice: Israeli daily newspaper Haaretz presented a study that looked at votes by EU members. It found that the country with the most pro-Israeli track record was Hungary.

Viktor Orban personally pledged his support to Israel. In December 2017, the European Council was about to condemn the United States for recognizing Jerusalem as the capital of the Jewish state by relocating their embassy. “Orban has taken firm action against this. When we formulate opinions about events in the Middle East, we must know that there is a life-and-death struggle in Israel that few understand,” Andras Heisler recalled the Prime Minister’s veto. He is the head of Hungary’s largest Jewish organization, the Federation of Hungarian Jewish Communities (Mazsihisz), who in other topics often criticizes the Hungarian government.

Then, in May 2018, Hungary again blocked the condemnation of the U.S. Embassy’s relocation. A Hungarian diplomat even attended the opening ceremony of the new U.S. Embassy in Jerusalem. In March 2019, Hungary was the first EU member state to open its own foreign trade representation office in the city. This gesture was significant, because the international community had previously refused to recognize Jerusalem as the capital of Israel. The city has prominent religious sites for Jews and Muslims alike, but its status was not settled by Israeli-Palestinian negotiations.

Hungary is considering gaining Israel’s sympathy with further gestures that are politically inexpensive. According to a source working for the foreign ministry, for example, the idea to somehow condemn the so-called BDS initiative also came up. This is an anti-Israeli and pro-Palestinian movement (Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions), which calls for a boycott of products coming from the territories occupied by Israel. In May 2019, the initiative was condemned by the German parliament as a form of anti-Semitism.

“We are trying to get the concept of new anti-Semitism to be accepted”

explained Tamir Wertzberger, Likud’s foreign affairs coordinator, who is personally working to have anti-Israeli sentiments identified as anti-Semitism by as many countries as possible in the EU. The theoretical background for this is as follows: classical anti-Semitism is based on religion, modern anti-Semitism is based on ethnicity, while new anti-Semitism is based on nationality and focuses on being anti-Israeli.

The importance of the Israeli relationship was also demonstrated by Orban’s ambassadorial picks. In 2013, he sent his former college dorm roommate and former chief of staff Andor Nagy to Tel Aviv. Nagy took advantage of the power of his relationship with Orban. “He absolutely had Orban’s trust, he was active, he took initiative,” a former diplomat to Tel Aviv said. “We were very pleased with Andor Nagy, and Levente Benko continues where he left off. They understood the complexity of the state of Israel, and we can fully cooperate with them,” a Likud official in Jerusalem praised Nagy and Benko, the career diplomat succeeding Andor Nagy in 2018.

THE COMMON ENEMY

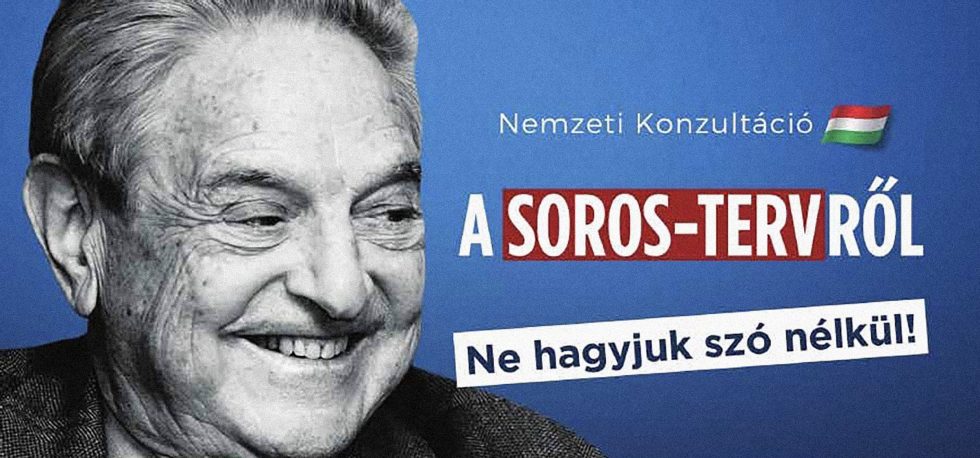

One of the Hungarian government’s billboard targeting George Soros

When Viktor Orban returned to Israel in 2018, he was already a well-known ally of Netanyahu and had his infamous anti-George Soros billboard campaign behind him, which was labeled as anti-Semitic by critics. This official visit was less intimate than his first one in 2005. Orban’s international reputation and Israeli name recognition had become completely different.

When Orban arrived at the Yad Vashem Holocaust Remembrance Center, a handful of protesters gathered. They were not removed by the security service, and remained in proximity of the ceremony that followed Orban’s tour inside the museum. A few of them shouted at Orban from within hearing distance, a source who was present remembered. The Prime Minister responded to the shouting by telling to those surrounding him that “well, he was a football player, and on the field, people say a lot harsher things,” a source who was present recalled. “However, you could see on Orban’s face that it didn’t feel good,” the source added.

The welcome that Orban received not only illustrates the polarization of Israeli domestic politics, but also the divisions within Jewish communities inside and outside of Israel. The same applies to opinions on the Hungarian government’s campaign targeting George Soros. This was best illustrated by Netanyahu’s first trip to Budapest in 2017, when he also met with leaders of the Central Eastern European region at the Visegrad Group-Israel Summit.

Israeli Ambassador to Hungary Yossi Amrani denounced the Hungarian government’s campaign targeting George Soros because of its anti-Semitic tone just a week and a half before Netanyahu’s visit. His statement made international news. However, not only the Hungarian but also the Israeli governing party did not share his views. Pro-Fidesz operatives of Likud and people close to Netanyahu were shocked at the ambassador’s action. “I was completely stunned. The next morning, I sent an sms to a Netanyahu adviser to escalate the issue [to Netanyahu] immediately because someone wanted to sabotage the Prime Minister’s visit to Hungary. The Soros campaign is a domestic political issue and it is a mistake to interfere. Moreover, we know who George Soros is, he is our enemy – I wrote that in the sms” a Likud official recalled. The ambassador’s statement was quickly withdrawn by the Israeli government before Netanyahu’s visit.

Ambassador Amrani was, in fact, instructed by two directors at the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs to issue the statement condemning the anti-Soros campaign. “It was the idea of his superiors, and the Ambassador was nervous about the possible outcome. It was not officially over for him after he voiced his criticism, but in practice he was done,” a Hungarian Jewish leader told about Amrani. The Israeli ambassador was eventually relocated to another post earlier than usual. “In the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs, a career bureaucracy has been formed over the decades, who still have old, long-established stereotypes about Orban, and that is why they confront Netanyahu,” the source claimed.

However, the perception of the Soros campaign in Israel also depends on political affiliation. “Majority of Likud-supporter Israelis appreciate Orban for his actions against George Soros,” Wertzberger said of the campaign. Eli Hazan, Director of Foreign Affairs at Likud, even provided Fidesz with a summary of information on Soros in 2017. According to Hazan, George Soros also gave financial support to leftist and pro-Palestinian NGO in Israel who “support terrorists or families of terrorists.” ”When it comes down to life or death I do everything to protect my country. I just informed Fidesz what Soros was doing,” Hazan told Direkt36. Netanyahu and his staff made similar allegations in public, which Soros rejected. Hazan also claimed that he had sent the information to Fidesz shortly before the launch of the Hungarian billboard campaign against Soros, hence he could not have been influencing it.

However, making an enemy out of Soros is part of a well thought-out political strategy and is actually the work of American-Israeli campaign consultants. One of them, George Birnbaum, recently talked openly and in detail about how they helped Likud and Fidesz build campaigns on targeting George Soros.

In addition to the common enemy, however, the ever-deepening relationship between Fidesz and Likud also brought Orban and Netanyahu an important common ally.

THE COMMON FRIEND

Viktor Orban in the White House with U.S. President Donald Trump on May 13, 2019. Photo: kormany.hu

The close relationship between Orban and Netanyahu was also a result of changes in U.S. foreign policy. “To put it simply, until the return to power of Netanyahu in 2009, the State of Israel relied almost exclusively on the United States when it came to international relations. That changed with President Obama, who was not anti-Israel, but still Netanyahu realized that from now on, Israel could no longer rely solely on U.S. support and needs new partners, for example in the United Nations” a senior Likud official in Jerusalem explained the shift in Israeli foreign policy that also led to the alliance with Viktor Orban.

Hungary vetoes and engages in political conflicts in the EU to advance Israel’s interests, and what it receives in return is primarily Netanyahu’s network of contacts. “Orban received support from Netanyahu already during his years in opposition, Netanyahu helped him open doors to Russia and China too,” an EU diplomat who maintains a good relationship with the Hungarian government told us. However, the main direction of establishing connections was the United States. “Some people think that the road to Washington goes through Tel Aviv,” a former foreign policy adviser to Viktor Orban said.

Hungarian-Israeli cooperation was already happening in Washington DC before Donald Trump took office in 2017. “From 2015, the Embassies have organized joint Holocaust remembrance and cultural events” Mazsihisz president Andras Heisler recalled. At these events, Reka Szemerkenyi, then Hungarian ambassador to the U.S., could have welcomed influential guests who might not have attended events organized solely by the Hungarians. The relationship with Israeli Ambassador to the U.S. Ron Dermer became a real asset from 2017. For example, Dermer organized a dinner in honor of Hungarian Minister of Foreign Affairs Peter Szijjarto, attracting important guests once again.

With the election of Donald Trump to the White House and a Republican administration, being an ally of Israel offered even more advantages, because political changes have brought Netanyahu and Trump very close together. “It was Bibi’s and Dermer’s previous Obama-bashing that really mattered to Trump, while he himself started courting the Jewish vote. The Israeli diplomacy’s current access to the White House is unbelievable, which is illustrated by the relocation of the U.S. Embassy to Jerusalem,” a former Obama administration official dealing with Jewish topics explained.

There were also rumors of Netanyahu arranging Orban’s invitation to the White House in May 2019. Back in the spring, a Hungarian government source told Direkt36 that the booking of a Trump-Orban meeting was also dependent on the outcome of the Israeli elections and Netanyahu’s reelection in April. Eventually, Netanyahu won and then a Trump-Orban meeting went ahead in May. However, the Israelis are deliberately exaggerating their role, according to a former foreign policy adviser to Viktor Orban. “The Israelis were involved in the Trump meeting indeed, but those who played important roles were Wess Mitchell [then Assistant Secretary of State for Europe] and Ambassador [David] Cornstein, as well as Hungary’s raising of its defense spending and buying weapons from the U.S.,” the former advisor explained.

However, it is unquestionable that Netanyahu has the ability to help achieve Hungarian foreign policy goals in the United States. For example, in a meeting with White House officials in Washington, which took place before Orban was invited and details of his visit were decided, U.S. officials explicitly said that Benjamin Netanyahu would support a trip by President Trump to Budapest, according to a Hungarian government official.

Alliances, however, also come with obligations, which sometimes puts Hungarian diplomacy in a difficult position. According to a diplomatic cable obtained earlier by Direkt36, Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Levente Magyar was asked by several U.S counterparts during his talks in Washington last November about when Hungary would finally relocate its own embassy to Jerusalem. Magyar replied that this could be a reality if other European countries, such as the Czech Republic, Romania or Italy first made similar decisions.

Israel is similarly putting pressure on Hungarian diplomacy on this issue. “If the Israelis ask when our embassy will relocate, we will politely reject them. We have opened a trade representation in Jerusalem so that we did not have to open a proper embassy […], with that, we have hit the wall,” a source working for the foreign ministry said. In the source’s view, this example also shows the extent to which Hungary’s Israel-policy is actually guided by interests only, considering that Hungary would engage in a disproportionately large conflict within the EU by moving its embassy to Jerusalem.

BUILDERS OF A JEWISH FUTURE

Viktor Orban visiting the Western Wall in Jerusalem in 2018. Chabad rabbi Slomo Koves standing behind him. Photo: kormany.hu

Increasingly closer ties between Orban and Netanyahu have brought major changes not only to Jerusalem and Washington, but also to Budapest in recent years. Netanyahu’s 2017 trip to Budapest made visible how serious the tensions are between his right-wing government and Mazsihisz, the organization representing the majority of Hungarian Jews, who are mostly left-wing. During the visit, Mazsihisz president Andras Heisler openly criticized not only Netanyahu’s diaspora policy, but also the fact that he withdrew the Israeli ambassador’s statement condemning the Soros campaign.

Why did Netanyahu side with Orban over Mazsihisz in their dispute? According to a former Hungarian government adviser on Israeli issues, Netanyahu’s role as prime minister is not to support self-serving actions of the Hungarian Jews. Since the state and power of Israel are the guarantee that the Holocaust cannot happen again, it is always in the prime interest of an Israeli Prime Minister to be in good terms with leaders of other countries, the source said.

A Mazsihisz representative offered a different explanation. “Under Netanyahu’s rule, Israel has become a strong great power, which, to Israel, has devalued the role and lobbying power of the Hungarian, American and all other diaspora communities. Likud prefers to build their own loyal Jewish communities and they do not want to bother dealing with local, embedded Jewish communities who are legitimate representations of the diaspora,” the source explained. The source also added that they are watching paralyzed as this conquest of building a pro-Likud diaspora involves enormous amount of resources.

Until the end of the 2000s, Mazsihisz was still in a monopoly position as the official representation of Hungarian Jews. It was at this time that an orthodox Jewish movement, favored by both the Orban government and Likud, began to flourish in Hungary. Without the help of the same orthodox movement, Benjamin Netanyahu could not have come to power in Israel.

In the 80s, Netanyahu was serving as Israeli Ambassador to the United Nations in New York. There, he met and began to admire Menachem Mendel Schneerson, also known as the Lubavitcher Rebbe, who was the spiritual leader of Chabad Lubavich, the orthodox Hasidic movement rooted in Russia. A decade later, in the last days of the 1996 Israeli campaign, followers of Chabad flooded the streets to campaign for Netanyahu and to thwart the Israeli-Palestinian peace process initiated by Yitzhak Rabin. The importance of their involvement was clear, given the narrow margin of Netanyahu’s surprising victory. “Netanyahu himself later acknowledged that he would not have won without Chabad,” Slomo Koves, Hungarian rabbi of the Chabad movement said.

The Chabad movement became a registered church in Hungary in 2004, named EMIH (Unified Hungarian Jewish Congregation). Almost immediately, Chabad began to establish contacts with, among others, children of Fidesz politicians who were discovering their Jewish roots. “Many Fidesz parents have called me terrified, telling me in disbelief that their children suddenly have two fridges in the kitchen!”, a former diplomat of the Orban government recalled, referring to how Chabad’s influence made some family members of Fidesz politicians take Kosher laws seriously.

Koves confirmed to Direkt36 that there were indeed some Fidesz politicians whose children were in contact with Chabad at that time already. According to a Mazsihisz representative, this was not a strictly Hungarian phenomenon: “From Trump to Putin, local representatives of the Chabad movement have developed good relationships with key political figures.” The source also added that

“developing such an influence in thirty years is an impressive achievement.”

The movement and church led by Koves in Hungary have in fact become increasingly close to Fidesz over the years. From the early 2010s, when various statues and memorials, controversial statements, or – from 2014 – the House of Fates Museum have caused international scandals, EMIH came to the aid of the Orban government multiple times. According to a Chabad source, however, their partnership was formed because, in the past, “Mazsihisz completely dominated relations to the Hungarian left-wing and practically pushed EMIH to the right”. Eventually, over the years, EMIH received increasing support from the Orban government, which helped them build an extensive web of institutions and a heartland with a media empire.

Fidesz, Likud and Chabad have become so intertwined by 2019 that Likud official Wertzberger, together with a member of the Hungarian Chabad movement, established the Likud Hungary Association. „In order to have a Jewish future in Hungary, Jews must marry with Jews and uphold Jewish religious laws”, this is how Chabad thinks of the Jewish community, Wertzberger said. From this perspective, Slomo Koves and EMIH-Chabad are the ones representing the future. According to Mazsihisz’s Andras Heisler, however, seventy percent of Hungarian Jews – assimilated, secularized, living in mixed marriages and just partly following religious customs – would not be considered Jews by Koves and Chabad’s definition.

Figures show that neither the backing of Fidesz nor Likud were able to realign Hungary’s Jewish community, moreover it resulted in a backlash. In 2019, Mazsihisz received 1% tax donations from more than 11,000 people while EMIH-Chabad from 2,800, with the number of donations for Mazsihisz sharply rising from the previous year. (In Hungary, taxpayers can donate 1% of their income tax to a registered church of their choice.) However, in September 2019, the Hungarian state recognised EMIH as “church in highest category”, which made them symbolically equal to Mazsihisz in addition to the extensive public funding already available to them.

Talking about his personal cooperation with the Hungarian Prime Minister, the head of EMIH-Chabad told Direkt36 that he puts Jewish interest first, everything else comes second.

“History is not being made according to big plans and schedules, the importance of personal elements, decisions and impressions matter much more. In the case of an influential politician such as Orban, who has a major influence over his party, his political community and a large part of society, feedbacks to him have an even greater significance”

Koves explained why connection to power is important for him and Chabad.

According to Koves, besides building EMIH institutions, Jewish interest also means the transformation of the Hungarian right. Orban indicated to Koves multiple times that he wanted to remove the stamp of anti-Semitism from the Hungarian right. “This is a historic process where you take two steps forward and one step back,” recalled Koves, who sees that the Prime Minister thinks that Hungary has a historic debt to find a way forward in its relationship with the Jews, and Israel’s role is important in it. According to a Chabad source, around 2012-2013, for example, Koves brought to the attention of the Prime Minister that the Arpad-striped flags appearing at Fidesz rallies (red and white striped flags that were also used by Hungarian Nazi sympathizers) evoke bad memories. After raising the issue with Orban, the flags have disappeared, according to the source. Another example is that anti-Israeli and pro-Palestinian views of the Hungarian right-wing press have ceased to exist.

“At the political level, Orban has absolute power as well as being the only one setting an intellectual direction for Fidesz. Below the surface, however, many still have to digest the pro-Israeli shift, and information gets to us that there is grumbling,” the Chabad source added. According to a Likud official, it is common for the whole Visegrad region to see opinions about local Jews and Israel separate from each other, and while anti-Semitism has often remained vivid, it does not rule out Israel-friendliness. “Today, Eastern Europe can already look to Israel as a role model: how a successful, capitalist, right-wing, nationalist transformation compared to the 80s looks like,” Koves said.

THE LEAGUE ONE FOOTBALL PLAYER AND HIS THIRD DIVISION FRIEND

Viktor Orban having a private discussion with Benjamin Netanyahu. Photo: kormany.hu

The 2017 Visegrad Group-Israel summit in Budapest further tightened the relationship between Orban and Netanyahu. “Orban and Bibi spent quite a lot of time in private, and one could feel the chemistry working between the two” a source familiar with the meeting recalled. Waiting for the Israeli prime minister to arrive, Orban remarked to those surrounding him how large-scale, charismatic, powerful politician Netanyahu was. A Chabad source also explained Orban’s affection by saying that the Prime Minister likes world-changing ideas, which are beyond daily politics, exactly the ideas that Netanyahu likes to repeat.

“I feel that the excellent Israeli-Hungarian relationship is partly due to our [personal] cooperation” Orban said in Jerusalem a year later in 2018. On February 19, 2019 during his joint press conference with Orban in Jerusalem again, Netanyahu listed how many times they had met in the weeks before: at the inauguration of Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil and at a conference in Warsaw. “We meet almost regularly” he said. The two have been in direct communicatins with each other for years, both over the phone and via sms. Aniko Levai and Sara Netanyahu, wifes of the Hungarian and Israeli Prime Ministers, have since also become good friends, according to several sources. Videos made during Netanyahu’s visit to Budapest also show the two wives walk arm in arm next to the husbands.

Orban is also inspired by Likud’s hinterland. American-Israeli political consultant Arthur Finkelstein, who invented the anti-Soros campaign and who also worked on Netanyahu’s 1996 election campaign, was an influential advisor to Fidesz from 2008 until his death in 2017. Fidesz still learns from Likud in terms of campaign technology. Recently, Fidesz’s number one think tank, Szazadveg, and the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs, which has close ties to Netanyahu, have begun building ties.

In his speech to the Fidesz intelligentsia in September 2019, Orban reportedly drew special attention to conservative Israeli philosopher Yoram Hazony’s book, The Virtue of Nationalism. The book argues against “liberal internationalism” and in favor of nation states. Orban and Hazony, a Likud supporter and a former adviser to Netanyahu, met in private in Budapest in March. In the background, the relationship is so close that the Hungarian government has been in talks since last year with Hazony, the director of the Herzl Institute in Jerusalem. They intend to establish a museum centered around Theodor Herzl, the Hungary-born father of Zionism. This was confirmed not only by foreign ministry sources but also by the diplomatic cable we have already referred to.

While Orban has been truly influenced by Israel and its right-wing circles, Netanyahu has no particular emotional attachment to Hungary. The Orban-Netanyahu relationship has been described asymmetric by several Hungarian and Israeli sources. According to a former Hungarian diplomat, one of Netanyahu’s main sources of information about Hungary was Zvi Herman Berkowitz, his family physician and confidant, who is of Transylvanian descent. According to a Hungarian Jewish leader who knows the Israeli Prime Minister in person, “he only thinks in the usual clichés, such as that Herzl was Hungarian.”

A Likud official in Jerusalem said that although there was a friendship between Orban and Netanyahu, they don’t share the same ideology. “Netanyahu does not usually talk about what he disagrees with because he is seeks common ground with his allies, but he is certainly different from Orban in at least two things. First, Netanyahu is more secular while Orban always talks about Christianity. Second, Likud sincerely believes in liberalism, democracy, the free market” the source added. But his opponents in Israel question that Netanyahu is indeed a liberal democrat. Netanyahu could be facing an indictment on multiple charges of corruption in weeks. In the current Israeli election campaign, he has been trying to discourage Palestinians from voting with the idea of installing cameras at polling stations in Arab neighborhoods.

A Hungarian source who personally knows both Netanyahu and Orban also pointed out that the influence of the two politicians is very different:

“Bibi is a politician on a much larger scale and has a much larger international presence. From his side, in addition to personal friendship, Netanyahu is bound to Orban by interests, less by admiration or respect. They are in different leagues, still, even a league one football player can be friends with a player from the third division.”

However, a former foreign policy adviser to Orban said that the personal part of the relationship should not be overestimated, because “between politicians there are interests, not friendships.”

However, the ever closer relationship with Netanyahu and Likud has also led to demands from Israel on more and more issues. “Recently, there have been diplomatic signals that Israel doesn’t really like close Hungarian-Turkish ties, president Erdogan’s frequent visits and Hungarian arms purchases from Turkey,” a member of the Hungarian parliament’s Committee on Foreign Affairs said. The Israeli-Turkish relationship reached its lowest point last year, Netanyahu even called Erdogan an anti-Semitic tyrant.

Earlier, Fidesz politicians had confidently built relationships with Iran, this has since become risky as well. “It has become an extremely sensitive area, and anyone associated with Iran is sure to be put on their black list,” a former diplomat of the Orban government said, adding that this could result in a black mark from the Americans too.

Israel also has interests in European affairs. Around the European Parliamentary elections, for example, Netanyahu and his people insisted that Fidesz should remain in the European People’s Party (EPP) because it was in Israel’s interest to have a strong ally inside the EPP, according to a Hungarian Jewish leader. A diplomat representing an EU country also talked about Israel’s interest in the largest Hungarian arms deal of recent times. Hungary is buying Leopard 2 tanks from Germany, and Israel was lobbying to have them equipped with certain additional devices coming from an Israeli company, instead of a French one.

The biggest problem for the Hungarian government, however, is that the one-sided pro-Israeli foreign policy will only benefit them as long as Netanyahu and Trump are in power. According to a Hungarian government source, they have recently signaled to the White House that although Hungary is trying to build a pro-Israeli coalition within the EU, the environment is hostile. A document circulated by Hungarian diplomats in the U.S. Congess, previously obtained by Direkt36 and 444.hu, states that “Hungary is alienating a large number of partners” by standing up for Israel.

Even the next Israeli government could be critical of Orban. After the September 17 election, it seems uncertain whether Netanyahu will remain in power. The Blue and White alliance, which is working on replacing Netanyahu and has obtained the largest number of mandates in the Knesset, has a poor opinion of the Hungarian government. One of their leaders, Yair Lapid, who is of Hungarian descent, made it clear in January that Orban should apologize for the anti-Semitic Soros campaign.