Companies dominate public lighting in Serbia with controversial Hungarian methods

„Šiofok, Kećkemet, Hodmezevašarhelj,” and several other Hungarians towns – written in a Serbianised way – were listed as references by a representative of a company called Elios, during a conference in Belgrade in December 2015.

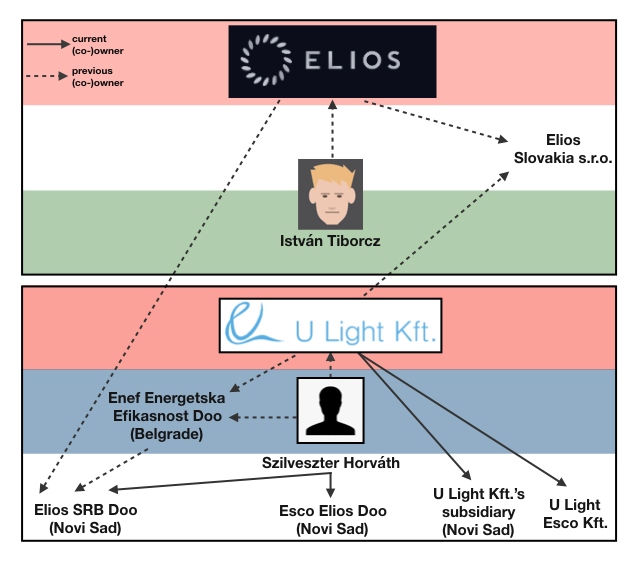

At that time, OLAF, the European Union’s Anti-Fraud Office, had already been investigating the Hungarian public lighting projects carried out by Elios, formerly co-owned by István Tiborcz, the son-in-law of Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban. OLAF found “serious irregularities” in the projects, but this did not prevent Elios from expanding abroad with the help of its Hungarian experience.

Since 2016, 25 million euros (8 billion forints) worth of Serbian public lighting tenders have been won by consortia that included at least one member linked to Elios, according to a research by Direkt36 and the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN). Some of these projects were won in cooperation with companies linked to the Serbian governing party.

A review of the Serbian tender documents also reveals the similarities between the two country’s projects: just like in Hungary, the Serbian tenders included strict requirements favourable for Elios-linked companies and ended up attracting little or no competition. Exactly these types of problems were found suspicious by OLAF in case of the Hungarian tenders.

Elios was still co-owned by Tiborcz when it established a Serbian subsidiary, Elios SRB. In April 2015, the PM’s son-in-law left Elios, and, in 2016, the ownership of the Serbian subsidiary also changed. The companies, however, didn’t get far away from Tiborcz by the time they started participating in Serbian public lighting projects. Elios was bought by a business group, which also had business relations with Tiborcz, while the Serbian subsidiary is currently co-owned by Bálint Erdei, a former co-owner of Elios and friend of Tiborcz.

We asked the companies involved, Viktor Orbán and Serbian Prime Minister Ana Brnabic whether the good relations between the Hungarian and Serbian governments, or the political connections of the Serbian and Hungarian lighting companies contributed to their success in Serbia. Brnabic replied that she is pleased that there are energy efficiency projects in Serbia, adding that she has nothing to do with public procurements. Viktor Orbán’s press chief, Bertalan Havasi replied that “the prime minister does not deal with business issues”.

On the new market with Hungarian experience

The modernization of public lighting in Hungary, which was planned to be largely funded by the European Union, started in 2010 in the Hungarian town of Hódmezővásárhely. The project, consisting of switching old sodium street lights to energy efficient LED, was a pioneer in Europe. The tender was won by a company with no such prior experience: Elios Innovativ Zrt., co-owned by István Tiborcz. Following the Hódmezővásárhely project – and partly due to the experience gained in that –Elios won dozens of public lighting tenders from 2013 onwards. Later, however, numerous irregularities were uncovered in these projects.

In 2015, OLAF started to investigate 35 projects carried out by the company and concluded that there had been “serious irregularities” and “conflicts of interests” in all of them, while in 17 cases, “mechanisms of organised fraud were built”.

One of the irregularities OLAF uncovered was that the technical requirements and prior experience required under the tender “were often unnecessarily high and/or not related to the subject of the contract.”

Hungarian authorities launched an investigation into the Elios case, but police said last year that they “had uncovered no crime.” The government, nevertheless, decided against invoicing the EU for funds originally earmarked to support the upgrade.

Shortly after the public lighting projects Hungarian, neighbouring countries also started to plan similar investments. With Hungarian experience in its pocket, Elios tried to take advantage of the international opportunities: as 24.hu earlier reported, it opened branches in Slovakia and Serbia.

In Serbia, most of the projects are implemented in public-private partnerships, so-called PPP constructions. It means that the investments are financed by private companies, while municipalities repay the costs in instalments, in 10-15 years.

According to the investigation of Direkt36 and BIRN, six companies related to Elios benefit from public lighting projects in Serbia. One of these companies (Elios SRB) was co-founded by Elios, while others are owned by U Light Kft and its former owner, Szilveszter Horvath. U Light had often been a competitor of Elios in Hungarian public lighting tenders, but later became its business partner both in Slovakia and in Serbia.

Hungarian websites 24.hu and Átlátszó reported last year about the existence and the first projects of these companies, however, since then, they have been even more successful in Serbian public lighting projects.

Direkt36 and BIRN revealed that out of the 15 PPP tenders that have been closed so far, twelve were awarded to consortia that included at least one member with links to Elios. In addition, they also won a non-PPP project. The total value of the investments is 25 million euros (8 billion forints). For four tenders, the winning consortia was the sole bidder. In the case of five projects, there had been one competitive bidder. However, the competition in these cases was rejected on the ground of having submitted incomplete tender documentation.

Hungarian model

Similar to the Hungarian public lighting projects, the tender requirements in Serbian were favourable for companies linked to Elios. Serbian tenders also required applicants to present high-value references and Elios-related companies seem to have taken advantage of this.

In July 2016, Elios SRB won its first Serbian public lighting project in Ada, Vojvodina. The project was awarded to a consortium which included, alongside several Serbian companies, Elios’ former competitor, U Light as a member. “Elios SRB, as a new company, did not have a reference, the Hungarian company showed a Hungarian reference,” said Árpád Koós, responsible for the Ada investment. He did not specify whether the projects of U Light or Elios were presented as reference.

A high-value reference was expected from applicants in the next tenders, too. The largest project was announced in Krusevac, where 12,545 light bulbs were to be replaced. For this job, applicants were required to have a reference of the replacement of twice as many, 25,090 light bulbs. Applicants were also required to present this work only from the last three years, and half of the reference had to come from a maximum of two projects.

As there had been no Serbian public lighting projects of that magnitude before Krusevac, companies did not have a choice but to present references gained in other countries.

“It is difficult to say that in a certain case what conditions are considered as ‘too narrow’, but it certainly seems excessive to ask for a reference which is double the amount of the planned investment,” Gabriella Nagy, head of Public Funds Programs of Transparency International Hungary told Direkt36. As a counter example, she reminded that in the Hungarian city of Kecskemét, where 4500 light bulbs were changed, the required reference was also of 4500 light bulbs.

The municipality of Krusevac told BIRN that the law on public procurement allows for tenders to stipulate a requirement of double the amount of the planned investment. “As we were among the first cities which started reconstruction of public lighting in this way, the requirement of experience of changing double the number of bulbs was one part of the evidence of the seriousness of the offer,” the press office wrote.

Zoran Stipanovic, a private contractor hired as a consultant and who wrote the tender requirements for Krusevac and for a number of other LED lighting tenders in Serbia, said that the requirement of double experience is a maximum by law and the „market didn’t require it to be reduced”.

Tender requirements were not only strict in Krusevac. In another project, applicants were expected to have at least a 3-million-euro (almost 1-billion-forint) annual income, and the description of the required light bulbs was also very detailed. In several other projects, companies were required to show a reference of at least two public lighting projects in the past three years, where at least 10 000 light bulbs were replaced.

Companies linked to Elios apparently knew how important references would be for their success in Serbia. Already before the first PPP tender was launched, in December 2015, Nóra Gombár, a representative of Elios attended a conference, which took place under the auspices of Ministry of Mining and Energy of Serbia. In her presentation, Gombár emphasized the importance of reference works, showing pictures of Elios’ projects carried out in Siófok, Kecskemét, Hódmezővásárhely and other Hungarian towns.

However, it was not clear which Elios company Gombár represented: she was introduced as an employee of the Hungarian Elios, but her presentation was about Elios SRB. Gombár does not hold any positions in these companies, but she is a shareholder in another Serbian company, Esco Elios, which can be linked to the Hungarian Elios through its owner.

Serbian politics in the background

The Serbian success of the Elios-related companies is also interesting due to the fact that, in many cases, they have won the tenders in cooperation with companies connected to the Serbian political elite.

One of these companies is the Slovenian Resalta, whose Serbian subsidiaries participate in public lighting projects in Ada, Nova Crnja, Zabalj, Petrovac na Mlavi and Krusevac. The Slovenian Resalta is co-owned by an investment fund of an American businessman, Mark Crandall. He previously worked with current Serbian Prime Minister Ana Brnabic: the PM was the director of Continental Wind Serbia, another company connected to Crandall. Brnabic held that position until she was appointed as Minister of Public Administration in 2016.

“I have worked with Mark Crandall and that’s no secret […] I really don’t understand; does that mean that Mark Crandall cannot work in Serbia anymore?” Brnabic asked BIRN when she was confronted with Resalta’s involvement in Serbian public lighting projects. She added that it’s “good that local governments are considering energy efficiency,” but she cannot tell them “what to do and how to do it”. Crandall wrote to BIRN that his investment fund only holds “something like 17%” of Resalta, and about its public lighting projects he knows “absolutely nothing”.

In Zabalj, Elios SRB won in cooperation with one of the largest companies of the Serbian energy sector, Energotehnika Juzna Backa. The current owner of this company, Dragoljub Zbiljić, is linked to the governing Serbian Progressive Party (SNS): he was the guarantor for a bank loan of 55 million dinars (almost 150 million forints) that SNS took in 2012, ahead of the parliamentary elections.

For Hungarian company data, we used the services of Opten.