Inside the crisis of the Hungarian opposition

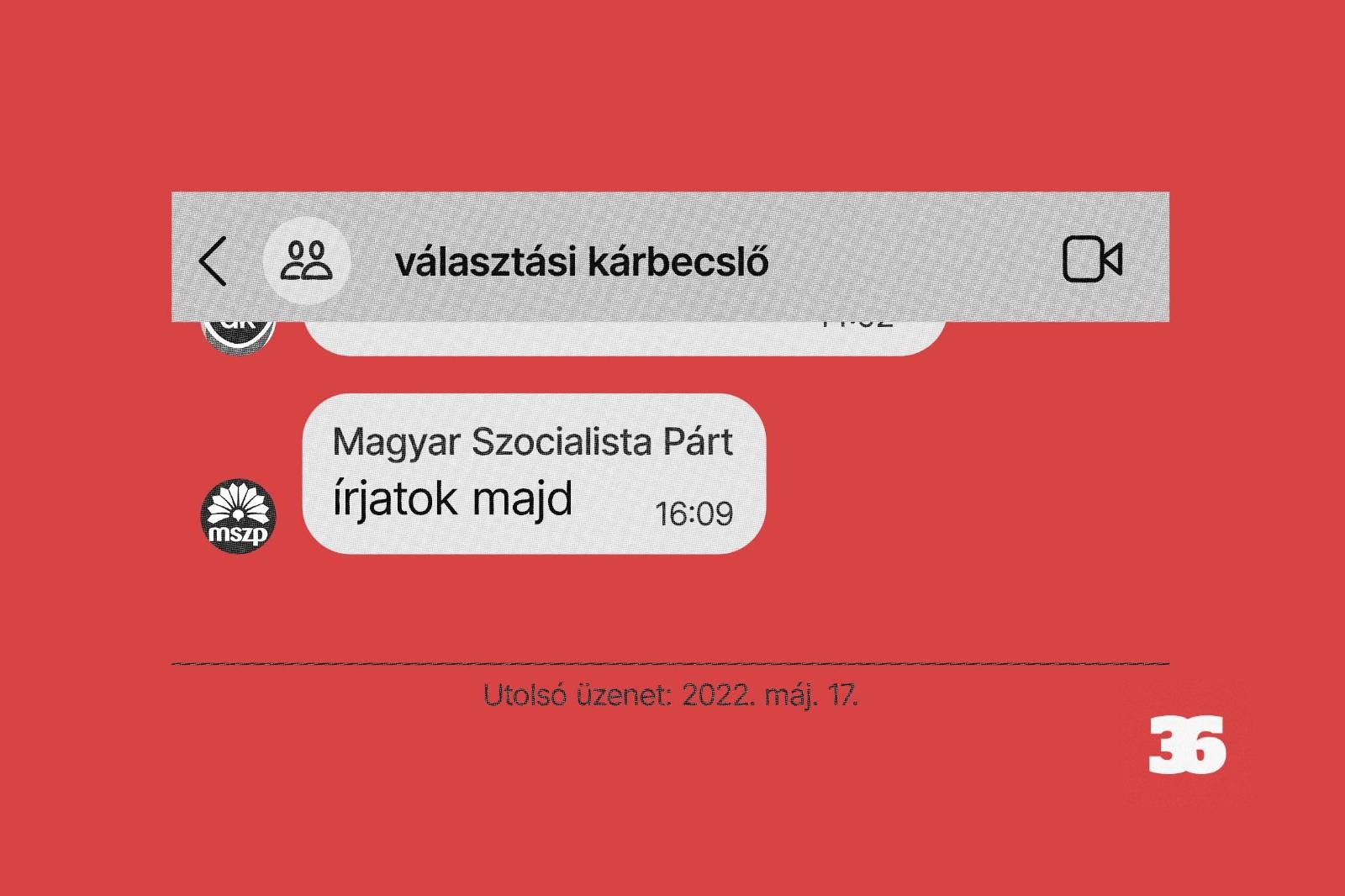

On 26th of April 2022, almost four weeks after the parliamentary elections that ended in a devastating defeat for the opposition alliance, the parties involved formed a chatgroup on the Signal messaging app. The group had a mixed composition, including some better-known politicians – such as DK MP Gergely Arató – but most of them were backbenchers who rarely appear in public. The Signal group named “election salvagers” and was one of the few joint attempts by the opposition to analyse the reasons behind their disastrous result and to draw conclusions from it.

But this work was essentially finished before it had even begun.

The members of the group had a few face-to-face meetings at DK’s Teréz boulvard office, shared a few documents via email, but did not do any real in-depth analyses. “We didn’t even analyze where Jobbik’s presumed voters had migrated,” recalled one member of the group, referring to the fact that the alliance received far fewer votes than the opposition parties separately in 2018, presumably because of the absence of Jobbik’s voters.

According to the participants, the face-to-face meetings were mostly therapeutic, and in the Signal group topics such as one member getting COVID and the other appearing in a political talk show on TV were discussed. On 17th of May, Ádám Agócs, the MSZP’s analyst, sent the last message to the group, saying “stay in touch”, but no one replied.

Not only have the parties that define themselves as the democratic opposition to Fidesz failed to analyze their defeat, but it is still not clear how they would be able to pose a real challenge to the government. Although the past year has seen record-high inflation, a shrinking economy and a series of austerity measures announced by the government, the opposition, which formed an alliance in last year’s elections, has failed to capitalize on this in the polls.

In recent months Direkt36 has interviewed dozens of opposition sources – politicians and consultants – to find out the reasons. Most of the sources gave us information about insider events on condition of anonymity.

Our research shows that although there have been some conspicuous opposition actions last year – such as Momentum’s dismantling the police cordon at the PM’s office or DK’s inflation billboard campaign blaming Orbán – the parties are mostly concerned not with Fidesz but with each other. Most of their energies are targeted at achieving a better position within the opposition with regard to the upcoming EP and municipal elections next summer. Small parties such as MSZP and Párbeszéd push for some kind of coalition that would enable them to win seats. DK – and to some extent Momentum – disagree, as they believe the 2024 elections will clear the stage from political organizations with no substantial support.

Although an agreement was reached by the two most influential figures in the opposition, Budapest Mayor Gergely Karácsony and DK leader Ferenc Gyurcsány, that they would not cross paths in the run-up to the elections, the conflict between the two of them has not been resolved. Gyurcsány still considers Karácsony too soft on the government, and DK approached politicians – including Krisztina Baranyi, the independent mayor of Budapest’s 9th district – a few months ago to run against Karácsony.

Amid the internal debates and posturing, the opposition has done little to challenge Fidesz’s hegemony. There was an earlier attempt after the oppositions’ success at the 2019 municipal elections, but that fizzled out quickly.

I. THE ATTEMPT

On December the 14th 2019, a Saturday, Szeged Mayor László Botka hosted the newly elected mayors who won the October municipal elections against Fidesz candidates in major cities. It was the opposition’s greatest success so far in the build-up of the Orbán regime since 2010, and Botka felt that this moment could be built on in the longer term.

The ten mayors gathered in a private room of a hotel in downtown Szeged for a day-long meeting. The mayor of Szeged, according to one of the participants, gave a relatively long speech about the need for opposition mayors to harmonize their moves, otherwise “Fidesz will grind them down”. According to another participant, Botka also spoke about the fact that since Fidesz only understands from strength, “we should build strength for ourselves”. According to the source, the meeting also took stock of the fact that roughly a third of the country’s population lives in opposition-run municipalities, and “this is where the idea that the resistance will be based on the cooperation of these cities stems from”.

Among other things, the idea of building opposition media was raised. Péter Márki-Zay, the mayor of Hódmezővásárhely, for example, wanted to set up a news agency – which was then referred to as the rural MTI (MTI being the state news agency) – while others favoured a joint newspaper in which national news would be covered as well as the local governments’ own stories. Several meetings were held between leaders and representatives of opposition municipalities to discuss these plans, but the initial momentum quickly faded.

One of the meetings was held in Dunaújváros in February 2020, where the head of a media company, Richárd Varga, pitched the plan of a newspaper that would have national news on the first three pages, with each municipality getting a page on the other. However, it was already clear that the idea did not enjoy unanimous support. One city leader, for example, encouraged Varga, who was giving a presentation, by wishing him success and sarcastically noting that he was “sure to find the resources to make it happen”. Varga responded by saying that “mayors are putting the cart before the horse, and it is not he who needs them but vice versa.”

But the problem was not just that some city leaders did not want to finance a project like this. Many practical problems arose from the fact that the media run by the different municipalities were in very different shapes, and it seemed difficult to make them cooperate. “Szeged, for example, has a holding company, while Ajka has a xeroxed monthly newspaper”, cited one source who took part in the discussions, and said that some municipalities might not have liked the joint publication because it would have offered less column space for their own stories. “The extra content is unfavourable because it means the mayor’s photo does not get printed in the paper,” the source said.

There was another media meeting in 2021 in Érd, and then in early 2022 at a mayors’ meeting in Pécs, but by then it was clear that the joint publication plan would not be realized. Although the people of Dunaújváros brought printed test copies of the newspaper to the meeting in Pécs, they were received coldly by the other mayors. A few city leaders nodded their heads in approval, but most of them remained silent, indicating that they did not back the idea. “After the meeting we called it off”, said one participant in the meeting.

The other idea of unseating the Orbán regime has not even got that far. There has also been talk among opposition municipalities of setting up their own network of public procurement consultants. This was deemed necessary because they believe that many public procurement contracts are awarded to pro-government contractors because the calls for bids are tailored to favour them. “We know that most tenders are decided before they are put out,” said a mayoral staff member, who said that was why it was considered important to remove government-connected procurement consultants – who are involved in issuing tenders – from the system.

This did not work out, and it soon became clear that the mayors could not be counted on to act as one. Botka, for example, wanted a joint statement against certain government measures, but not everyone agreed. There were mayors who did not want to deal with national political issues, or who simply feared losing out on certain government resources, so even the drafting of joint statements proved difficult.

The discussion took place in a Signal group, and according to one of the mayors involved, while the Szeged mayor wanted to use more radical phrases (the source says he even suggested to his colleagues that they should leave the Association of Cities with County Authority), several mayors wanted to tone down the texts or did not contribute to the discussion at all.

The Mayor of Budapest, Gergely Karácsony, also made an attempt to build an alliance between the opposition municipalities. He initiated the Free Cities organization, which sought to unite smaller opposition municipalities alongside the larger cities. Discussions on media cooperation were partly held within this framework, and the issue of joint action against the government was also raised at this forum.

Karácsony’s staff pushed for this because this national build-up project was also part of the Mayor’s longer-term political ambitions. However, the Free Cities initiative died before Karácsony withdrew from the primary for the premiership. The organization’s Facebook page has less than 4,000 followers, the last post is from January 2021, and the website is no longer available.

II. WILT

The opposition camp had high hopes for the 2022 parliamentary elections after the mobilizing primary election, but at the end of the campaign led by Péter Márki-Zay, the opposition party alliance suffered a shocking defeat.

For example, a typical story is what happened shortly after the April 2022 elections at the Párbeszéd’s board meeting. It was attended by elected MPs and other people who play important roles in the party, in addition to the members of the bureau. According to one of the participants, they were “venting” to each other while waiting for the official start of the meeting: it was mentioned that Fidesz was gaining strength in rural settlements, while the opposition was losing votes in places considered left leaning.

But if some participants had expected the meeting to go into a deeper analysis of the electoral defeat, they were disappointed.

The official part of the meeting started when the Mayor of Budapest, Gergely Karácsony (then also the party’s co-chairman), arrived a little late and made it clear to everyone that the most important topic was not the election defeat. “It would be important to analyze the results, but we are in a situation here because of the parliamentary mandate’s replacement”, recalled one of the participants of the meeting on the occasion of the mayor’s entrance. Karácsony referred to the fact that LMP had received a seat from DK under the opposition’s election agreement to pass the threshold required to form a parliamentary faction. The other parties believed that LMP had become beholden to DK and the two parties could become too close.

Karácsony raised the need to prevent this, according to several participants in the meeting. According to one source, the mayor said that they should help LMP out with a seat, as this would allow the grand green alliance to be rebuilt. “There is one last chance to get LMP off DK,” the source recalled the gist of what Karácsony said.

“There was all talk, no action for quite a while” recalled one source, adding that the meeting ended up being completely inconclusive, and no solution was found to tie LMP to them. On behalf of Karácsony, the press officer of the Mayor’s office answered to all questions concerning the Mayor that “the Mayor of Budapest does not deal with pathetic political gossip”.

Tímea Szabó, the leader of the Párbeszéd parliamentary group, said “I can’t remember the exact details after all this time, but it is certain that neither LMP nor DK, let alone their relationship with each other, was a central topic of this meeting.”

Párbeszéd was not the only opposition party to avoid facing up to its election defeat. In the case of the MSZP, MEP István Ujhelyi tried to persuade the party to do so, but he was not very successful.

Shortly after the election, on 23th of April, the MSZP leadership convened a meeting of the electoral board at the party’s Villányi street headquarters. In the auditorium, called Room 200, about 150 party members who were leading the campaign on the ground gathered to assess the election results, which had also shocked the socialists.

Two of the party’s co-presidents spoke before the agenda, but there was also an unscheduled speaker. Shortly before the event, István Ujhelyi indicated to the party leadership that he also wanted to address the party members. He did not specify what he planned to talk about.

Ujhelyi presented some slides to the board. He spoke about the MSZP’s renewal through the creation of local communities modelled on the Fidesz’s civic circles, and about a new opening between the party and forms of civil organisation – this was the initiative of the Community of Opportunity. The MEP was provocative, as one socialist politician who followed the presentation on the spot saying that one of his slides had the slogan “the carnation is wilting”. The slides obtained by Direkt36 did not include this text, but a colleague of the MEP admitted that he mentioned it in his speech.

Soon afterwards, Ujhelyi also applied for the position of co-chair of the party, but this attempt failed, as it was opposed by the current leadership of the MSZP . “Did I make a mistake in holding up a mirror to ourselves with blunt honesty? Maybe,” Ujhelyi wrote in a Facebook post about his resignation. The MSZP, however, has now told Direkt36 that the politician was forced out of the party because he wanted to carry out an “audacious organizational restructuring”. Ujhelyi told Direkt36 that his plan was “not adventurism, but a courageous rebirth”. He added, “I don’t want to look back and I wish my friends good luck.”

Momentum was also mainly occupied by resolving internal conflicts in the weeks following the election. The party had to elect a new chairman after the previous leader, Anna Donáth, announced that she would not run for the post again because she was expecting a child. The new president became Ferenc Gelencsér, who came into conflict with former party president András Fekete-Győr.

After the elections, Fekete-Győr became the leader of the Momentum parliamentary group, but at the beginning of July the party’s leadership called him back, with Gelencsér taking his place. According to the official justification, the change was made “in order to ensure the ideal functioning and efficient workload management of the party”. According to several sources in Momentum, Fekete-Győr did not like the change. Gelencsér told Direkt36 that after he was recalled from the fraction leadership, he sent Fekete-Győr on a tour of the country to cheer up Momentum’s local communities after the lost election. Fekete-Győr denied to Direkt36 that Gelencsér made him go on the tour, saying that he himself had raised the issue with the party’s MEP, Katalin Cseh, and the president in a 3-person meeting. He added that “I have heard from other people that the president had sent me on a tour, but that was not the case.”

There was one party, however, that was not bound by internal conflicts. DK, the Demokratikus Koalíció, already renowned for its discipline, saw an opportunity in the aftermath of its electoral defeat and launched its campaign in early autumn.

III. OPERATION DK

Ferenc Gyurcsány and Klára Dobrev were about to make a big announcement. The power couple, who play a leading role in the DK, called a private meeting on 15th of September last year at the home of former MNB (Hungarian National Bank) vice-president Zoltán Bodnár in the 2nd district of Budapest. Among those invited were sociologist Mária Vásárhelyi, Zoltán Lakner, editor-in-chief of the public weekly Jelen, economist Dóra Győrffy, writer András Bruck , campaign expert Gábor Bruck and former SZDSZ minister Gábor Kuncze.

The guests gathered in Bodnár’s elegant living room, decorated with paintings, next to a piano. They sat around a table with Dobrev and Gyurcsány at either end.

Gyurcsány and his wife announced that they would go public the next day with their plan to form a shadow government. Dobrev said that the Orbán government would not be able to count on EU funds for some time, and that the economic difficulties meant that Fidesz’s popularity was expected to plummet, while support for DK could rise sharply. They said that they did not see any other opposition party to stand a chance of success. “MSZP was treated as non-existent,” said one source at the meeting. Only Momentum was mentioned as a factor – whose popular support, they believe, could only be matched with Mi Hazánk (the extreme right radical nationalist party) – and no other political organisation was mentioned.

However, Gyurcsány and Dobrev also indicated that they do not regard Momentum as a very serious player either. They said that Momentum had learnt about the formation of the shadow government four or five weeks earlier, and that the DK feared that Momentum would somehow block their plan, for example by proposing a cross-party shadow government, which the DK members said would have led to endless negotiations. Momentum, however, has not come up with any ideas to block DK’s plans. One source at the meeting said he got the impression that Gyurcsány and her wife were genuinely surprised by this and considered Momentum’s inaction to be amateurish.

At the meeting in Bodnár’s apartment, Dobrev did not deny that their plan was intended to sharpen the competition between the opposition parties. “Competition is a good thing, it is a tool to clear the opposition spectrum,” the DK politician said, according to a source present at the meeting. We asked DK to comment the statements relating to them in the article, but the party would only say that it “does not comment on rumors.”

It is not only by forming the shadow government that DK has made it clear to the other parties that it wants to dominate the opposition field. After last year’s elections, they actively sought ways to lure more politicians away from the others. In the past year and a half, they have recruited Olivio Kocsis-Cake, the party director of Párbeszéd, Balázs Szücs, the deputy mayor of Erzsébetváros, Ferenc Varga, a member of parliament who had previously left Jobbik, and Alexandra Bodrozsán and György Buzinkay from Momentum, along with Tibor Déri, the mayor of Újpest.

Although DK sources in background interviews referred to the transfers as an “organic process”, which they say is a natural part of being the largest opposition party, Direkt36’s research shows that most of the transfers were very much planned and such a priority for the party that the first steps were often taken by the party’s top leaders.

“One is surprised when it is Ferenc Gyurcsány on the other end,” recalled a Budapest Momentum politician who eventually turned down the invitation to transfer, when contacted by DK. In addition to Gyurcsány, the politician was also called by Dobrev and had coffee with her on several occasions. The politician said that it felt like being poached by a major multinational firm. Dobrev praised the politician’s talent, achievements and young age. The politician was approached by DK with several offers a few months apart, which were all turned down.

A good example of the planned and deliberate way in which DK negotiated is the ultimately unsuccessful transfer attempt in Nyíregyháza. Ferenc Gyurcsány met the local MSZP leader András Jeszenszki at the beginning of this year and talked to him about the transfer, and then left the rest to Attila Jószai, the former DK deputy mayor of Szigetszentmiklós, and Judit Ráczné Földi, who has been an MP for DK since March.

Following Gyurcsány’s visit, Jószai and the others made several trips to the city to meet with local MSZP members. On one of their visits, they were joined by members of the local executive and the multi-county regional director. About twenty people were crammed into a room converted from a former convenience store.

Jószai’s team came prepared: they put the names of other parties’ officials in the city in front of the local DK members in an Excel spreadsheet. They asked their party colleagues to rate people on a scale of 10, depending on how sympathetic they were to DK and how likely they were to switch parties. They were then to be charged with making enquiries, but various local disagreements stalled the negotiation process and no switches were made at that time.

There have been examples where personal resentment has played a part in the transfer. Olivio Kocsis-Cake, previously of Párbeszéd, was a Member of Parliament in the previous term, but was not shortlisted for a position guaranteeing a mandate on the opposition’s 2022 joint list. In addition, he was further moved down the list during the campaign to meet Péter Márki-Zay’s demand to secure three seats for candidates of Roma origin.

Kocsis-Cake’s grievances were compounded by the fact that after the election a contest was announced for his party director position. He eventually managed to keep it, but several of his party colleagues say he resented the party’s move. Kocsis-Cake finally announced his switch to DK in January 2023, and bid farewell to his former party in a message posted on an closed Facebook group. According to several sources familiar with the message, he wrote that “we need a big party” because he believes that having too many small ones doesn’t work. However, he also cited personal grievances, such as not being better placed on the 2022 opposition list and thus not being re-elected to parliament. (Kocsis-Cake did not respond to our questions about the circumstances of his defection.)

So DK has also successfully lured politicians from Párbeszéd, but still has not managed to get a grip on the party’s best-known and most influential politician, Budapest Mayor Gergely Karácsony.

IV. GYURCSÁNY VS. KARÁCSONY

Krisztina Baranyi, the independent mayor of the 9th district, was asked an unexpected question this spring after a meeting of the Budapest Municipal Assembly. She was already outdoors, chatting with a small group of people next to parked cars, when one of them – a politician from the DK party – approached her: “Kriszta, don’t you want to be the mayor of Budapest?”

Baranyi indicated that she had no such intention, but a few weeks later DK proposed her again, wondering if she had changed her mind. The mayor indicated once more that she was not interested.

Baranyi was not the only politician or public figure to be approached by DK with the idea of running for mayor. According to an opposition politician, he was told by Gyurcsány himself that they had several candidates in mind, and mentioned Zoltán Somogyi, a political consultant and founder of the Political Capital think tank as an example.

According to other sources and public information, the names of Anett Bősz, the DK-backed deputy mayor or Budapest and Sándor Szaniszló, the DK mayor of the 18th district were also mentioned in the party.

Somogyi told Direkt36 that he had heard rumours that DK would ask him to run for mayor, but he had not received any official enquiries. According to him, when he asked the party about their plans, they admitted that his name had been floated as an idea in internal discussions. “I only got vague answers. But I told them that they might let me know if they have such ideas.” Somogyi added that he has no ambitions to run for the position.

Bősz and Szaniszló did not respond to questions sent to them.

DK’s search for a mayoral candidate also shows that the party is not satisfied with Gergely Karácsony and wants to find someone either to challenge him or to place pressure on him to make concessions in various political bargains.

As Direkt36 previously revealed, the conflict between Karácsony and DK goes back years. There were clashes between them shortly after the 2019 election, and the relationship became even more acrimonious in the 2022 election campaign. DK politicians first resented Karácsony’s campaign against Klára Dobrev after his withdrawal in the primaries, and then, when the campaign revealed the leadership shortcomings of Péter Márki-Zay, who was eventually chosen as the joint candidate for prime minister, they partly blamed Karácsony. “Fuck you, Gergő, you brought this man on board, it’s on you”, told Gyurcsány the mayor at a meeting in early 2022.

The old grievances have not gone away. Gyurcsány also raised the issue of Karácsony not being tough enough at the meeting at Zoltán Bodnár’s house before the shadow government was announced. He also criticised him for not treating Budapest as an important source of strength for the opposition.

The DK chairman also voiced his dissatisfaction with Karácsony in public. He did so most explicitly in an interview to Youtube channel Partizán last September. At the time, he said that it was “by default” that the current mayor would have the support of DK in the 2024 municipal campaign. “The mayor’s job is to renovate Blaha Lujza Square and create a bike lane on Üllői street. Or the job is to organise the community of the most free Hungarian city against the authoritarian regime. This is the dilemma. I am of the opinion that this is a serious political opportunity and responsibility,” Gyurcsány explained on Partizán.

In a recent private conversation with an opposition politician, Gyurcsány was even more explicit. When the politician asked him why he was critical with Karácsony, he replied, “My dear, because he had the opportunity to organise the opposition. And he missed it.” According to the source, Gyurcsány explained that the position of Mayor of Budapest would be particularly suitable for organising the opposition, but Karácsony does not act accordingly.

For Karácsony, however, it is a reassurance that according to his staff, his position is stable in the opinion polls (several Fidesz sources reported similar opinion polls). According to an opposition adviser, a few months ago Gergely Karácsony’s adviser Zoltán Gál J. told him that they had feared that his withdrawal from the primary would lead to a drop in support, but now he said that “Gergő is doing really well, so we are calm.” Deputy mayor of Budapest Ambrus Kiss also told Direkt36 that “he has only seen good polls of Karácsony”.

Thus, DK is no longer looking so intensively for possible challengers to Karácsony, and is concentrating instead on increasing its influence in the Municipal Assembly, without which the mayor has very little room for manoeuvre. “If DK reaches 10 seats, Gergő can’t even go to the toilet without their permission,” an opposition campaign consultant explained the consequences of DK winning more seats in the municipality.

According to a close associate of Karácsony, relations with DK are now calm. The reason, as the source revealed, is that Karácsony is focusing only on Budapest and the local municipal governments, and not on the EP election campaign. There was already a similar agreement between Karácsony and Gyurcsány in 2019, and according to the source, “there is a similar demand from DK now”. The two political leaders have now negotiated this through intermediaries, and the source said that although no document has been officially signed, “there is peace in Budapest”.

Of course, this does not prevent other opposition parties from working against DK or other parties.

V. “Dialogue for mandates”

A Momentum kordonbontással is próbálta felhívni magára is a figyelmet. Forrás: Momentum Facebook-oldala

In January 2023, MSZP sent a letter to the other parties allied in the 2022 campaign, inviting them to its Villányi street headquarters in Budapest to discuss the cooperation. Jobbik and Párbeszéd said yes, but LMP and DK quickly indicated that they did not consider it timely. The meeting did not take place then, but only in May, after the Socialists repeated the invitation several times.

However, these discussions have not yet produced any tangible results. This is not necessarily surprising, given the sceptical attitude of many parties to cooperation between the parties. One such party is DK, which has been shying away from the talks and is currently the opposition party with the highest support in opinion polls. According to one participant in the talks, the fact that Gergely Arató, representing DK, “skillfully avoids questions and does not give specifics” is a good tell.

The source added, however, that the Villányi street talks are of no significance because the host Socialists have become debilitated. “The MSZP is obviously not able to dictate, nobody takes them seriously anymore,” the politician said.

The MSZP, once in government for several terms and for a long time the largest party in the country, is now a shadow of itself. Surveys show that its support among certain party voters is just around 4-5 percent, which means that it would not necessarily make it into the parliament if it ran on its own in a parliamentary election today.

Even more desperate than the MSZP is Párbeszéd, which has a rating of around 2 percent. If they want to win a seat in next year’s European elections, they need to join forces with other parties and put forward a joint party list.

At the end of last year, Gergely Karácsony also initiated talks with Momentum’s president, Ferenc Gelencsér, on this issue. At their meetings in December and January, he raised the idea of a joint EP list. The mayor argued that voters often indicate each other’s parties as a second preference, so that a list of “two smaller, more European” parties could be successful.

The Momentum president did not rule out the possibility. He suggested, however, to think about other forms of cooperation besides a common EP list. Gelencsér told Direkt36 that he felt using the term “merger” would be inadequate, but that he would imagine a “closer and longer-term partnership” and “would not rule out more frequent consultations.”

However, the rapprochement between Momentum and Párbeszéd is hampered by preparations for the local elections. Párbeszéd objects to Gelencsér’s ambition to become mayor of the 1st district, a post currently held by Párbeszéd politician Márta V. Naszályi. In response to Direkt36’s question about Gelencsér’s candidacy for mayor, the party said that the “perceived or real mayoral ambitions” of its politicians do not influence the pre-election negotiations.

In addition, it is not clear whether Momentum would support a joint list. “It has been taken into consideration, but a significant part of party members expressed that they prefer running independently in the EP elections. Many are of the opinion that the EP election will clean the opposition landscape, small parties with only a few percent of support will no longer have seats at the table,” a source at Momentum said.

Thus, more recently Párbeszéd has been feeling its way towards LMP. According to several Párbeszéd politicians, the priority has recently been to establish some kind of cooperation with LMP on a joint EP candidacy. The joint candidacy of the two parties is not necessarily influenced by the fact that both parties have announced their EP lists’ frontrunners: Párbeszéd named former MEP Benedek Jávor in March, while LMP named co-chair Péter Ungár on the 9th of September. The latter has already declared that he will vacate his seat in the EP if elected.

“LMP may even separate the list positions from the mandates” – Tímea Szabó, leader of the Párbeszéd parliamentary group, told Direkt36 , referring to the fact that the negotiations between the two parties are ongoing despite the announcements. Péter Ungár declined to respond to questions about the future of the two parties.

While the former allied parties are busy with these arrangements, they have not been able to benefit substantially from the economic difficulties that have affected Fidesz’s popularity. Yet one political analyst argues, based on internal measurements, that they could have done so.

“It is a common misconception that Fidesz has not lost any popular support despite the economic crisis. There are few bigger misconceptions than this. They had 3 million voters, and according to our measurements they lost 700,000 of them, more than 20 percent,” said the analyst, who believes that these voters did not migrate to the opposition parties running together in 2022. Instead, the satirical party Kétfarkú Kutyapárt and Mi Hazánk could benefit from these undecideds.

According to Krisztina Baranyi, the reason for this is that none of the previously allied opposition parties wants to build itself, they are only interested in positions. “The slogan of the opposition could be dialogue for seats. Party leaders do not negotiate with each other about anything other than positions. They are not talking about visions or programmes, but about seats on supervisory boards and external committees,” said the Ferencváros mayor.

While there have been attempts by some parties to build a campaign to undermine government support, they have quickly come up against their own limitations.

For example, several party members in Momentum have urged the party leadership to do something about inflation, but an internal survey conducted in the spring showed that voters do not consider Momentum competent enough to do so, so it is better to come up with a different central message. Several Momentum politicians confirmed to Direkt36 that there had been such a survey, and they also said that this was one of the reasons why the party had finally chosen education as its number one campaign issue.

DK’s inflation campaign launched at the end of the spring was not very successful either: at least, even though billboards were put up in vain saying that the inflation caused by the Orbán government would be overcome by Klára Dobrev, the party’s support did not improve substantially. According to the latest polls by the Republikon Institute in August, DK’s support even declined somewhat compared to the previous month.

It is no wonder that even Fidesz does not seriously fear the parties of the former opposition alliance.

Gergely Gulyás, the Minister of the Prime Minister’s Office, spoke openly about this at a meeting of the Association of Cities with County Authority (MJVSZ) last year, and as these meetings are held behind closed doors, the atmosphere is more relaxed between government and opposition politicians. According to one participant, Gulyás also let himself go, and at one point, in front of the opposition mayors present, he turned to MJVSZ president Károly Szita and said, “let’s be honest, we can’t really wish for a better opposition than the one we have now.”