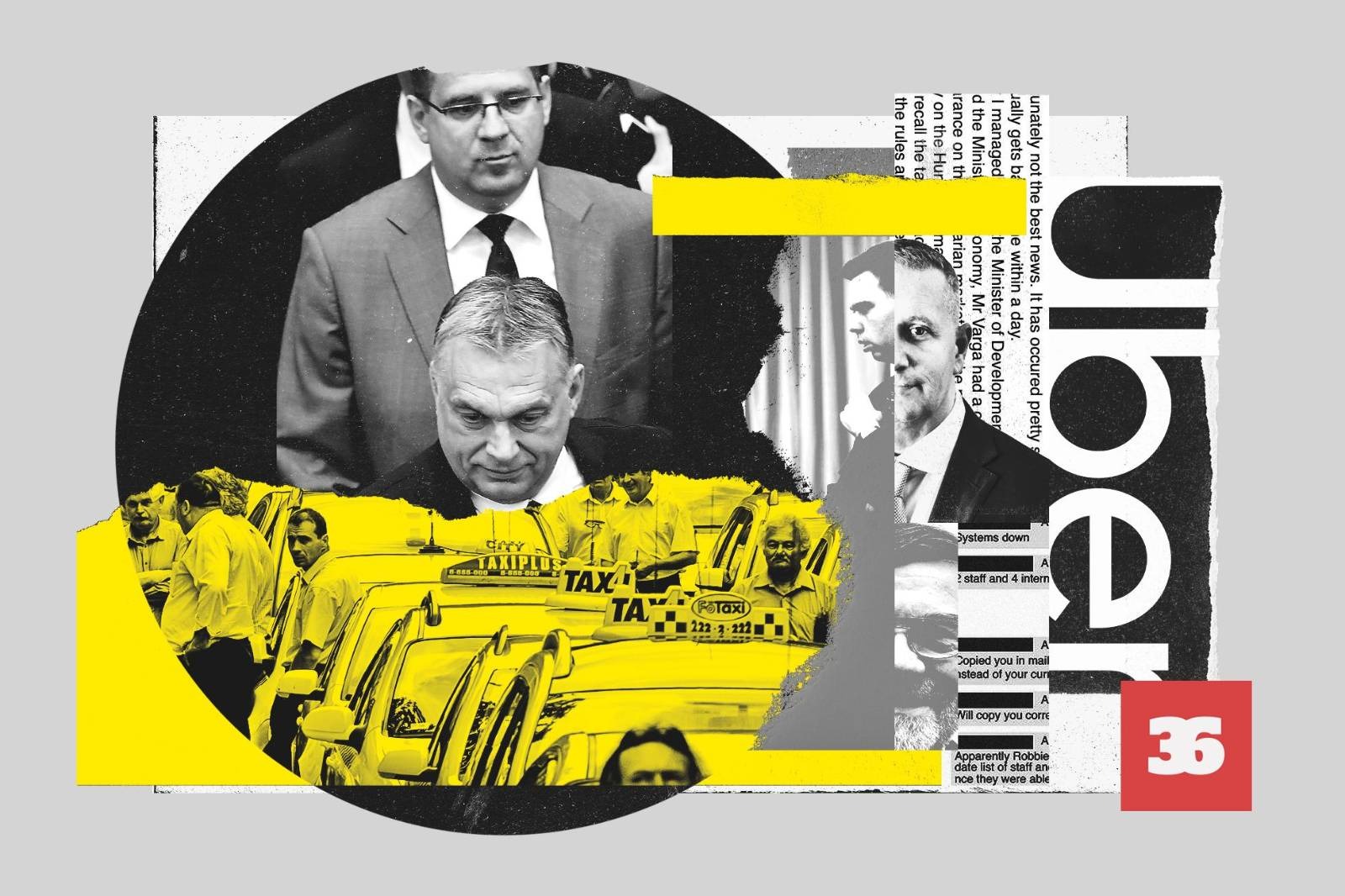

Leaked files of Uber reveal secret lobbying operations in Hungary

Representatives of Uber, the U.S. company that disrupted the taxi industry through its smartphone application, were dismayed by the message they received from then National Development Minister Miklós Seszták in February 2015.

Uber had already been present in Budapest for months, and their mobile app-based service, which was generally cheaper than traditional taxi prices, was becoming increasingly popular. In the meantime, however, they were aware that the government was working on a new regulation that could be detrimental to them. In order to change the law, they wanted to meet local decision-makers and signed up with several lobbyists in Hungary to do so. One of them was a man called Tamás Sárdi, who had extensive government connections and was at the time a business associate of István Tiborcz, the Prime Minister’s son-in-law.

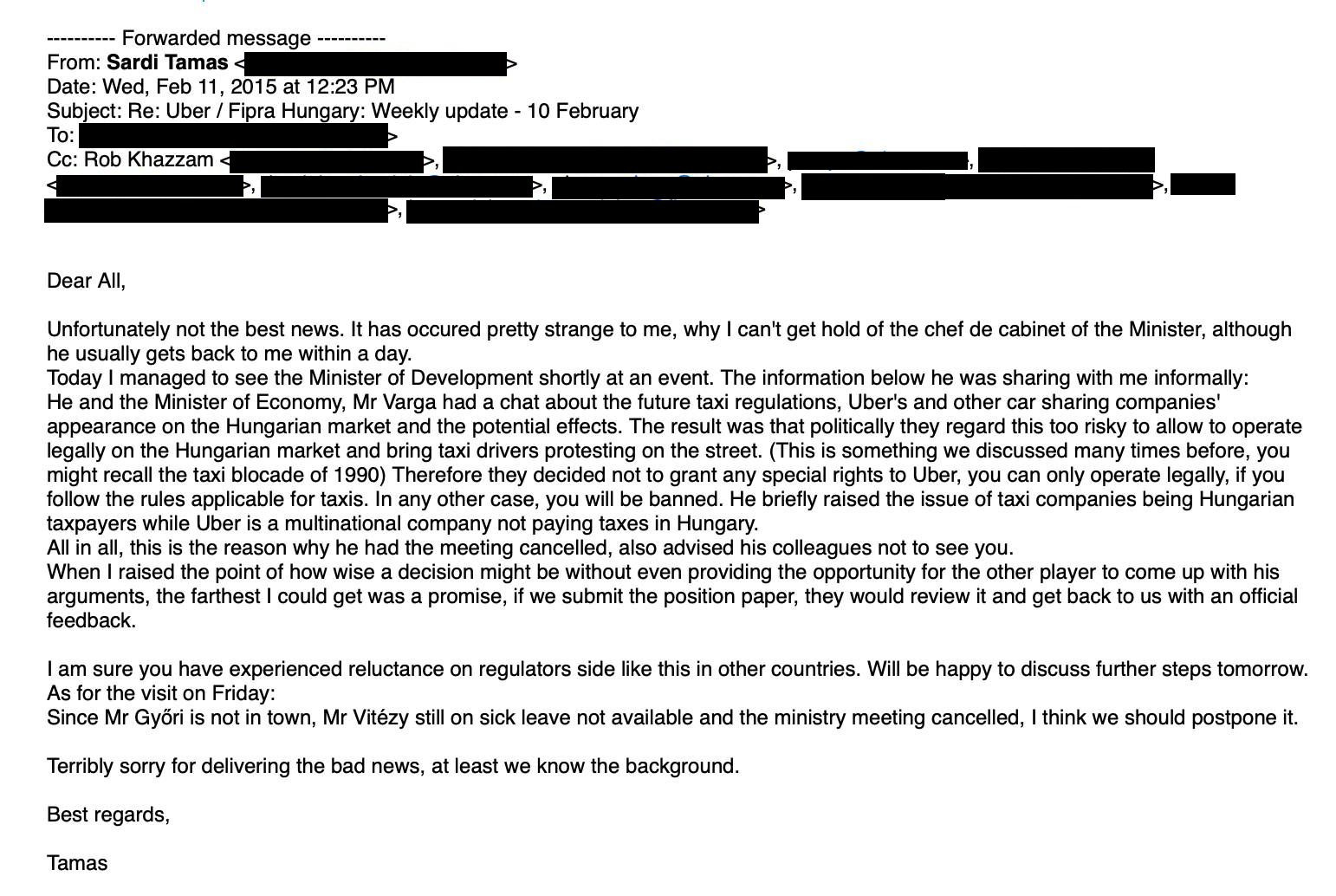

Sárdi managed to arrange for the Uber representatives to be received by minister Miklós Seszták, whose portfolio included transportation, but a few days before the meeting, scheduled for 13 February 2015, the minister’s secretariat unexpectedly cancelled the meeting without offering an alternative date. The minister’s chief of staff then did not answer Sárdi’s phone, although he had always been easily available.

The frustrated lobbyist finally managed to catch Seszták at an event and asked him what had happened. The minister said that he and Finance Minister Mihály Varga had discussed the ride-sharing services issue. They concluded that it would be too dangerous politically to allow Uber to operate freely in Hungary, risking a strike by taxi drivers. Seszták said that, because of this political risk, the decision was that Uber should not be given any special treatment. The minister also told Sárdi that he had instructed his colleagues not to meet Uber’s representatives.

Sardi reported this episode to Uber in an email sent on February 11, 2015. The letter is one of nearly 124,000 documents leaked about Uber’s lobbying activities between 2013 and 2017. The documents were obtained by the British newspaper Guardian, which then shared them with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ). Direkt36 was the only Hungarian member of the project, which involved more than 180 journalists from 29 countries.

These documents show that Uber and its lobbyists managed to have face-to-face meetings with several ministers and other high-level decision-makers, but failed to get the rules changed in their favor, leading to the company’s departure from the Hungarian market in early 2016. The government’s official position was that Uber could stay if they complied with the taxi rules. However, Direkt36’s research also showed that while Uber’s lobbying efforts have been hampered, similar efforts by domestic taxi drivers have been much more effective. This was shown, for example, by the fact that when they approached Prime Minister Viktor Orbán personally at one point, they received a positive response from his staff within a short time.

The internal documents, known as Uber Files, also revealed the following previously unreported details:

- – Imre Kónya, a former Minister of Interior serving in the early 90s, was one of the local consultants who worked for Uber. He personally negotiated with Sándor Pintér, the current Minister of Interior, on behalf of the company

- – One of Uber’s employees contacted former Minister of Economy János Kóka, who was helpful, saying that he didn’t like taxi drivers anyway. In the end, however, Kóka didn’t end up working for Uber

- – One of the first official meetings Uber had was with Dávid Vitézy, head of Budapest Transit Center (BKK) back then (now State Secretary for Transport at the Ministry of Technology and Industry), but he was losing his influence in the capital at the time

- – Uber came under heavy pressure from the Hungarian tax authority. Tax inspectors probed Uber drivers hundreds of times, and during a raid on the company’s Budapest office, Uber even had to use a secret “kill switch” to make data stored on its employees’ computers inaccessible to authorities

- – Uber was even inspected for an ice cream distribution PR operation

- – By mid-2016, it was clear that the taxi law would make Uber’s operations illegal for good. “Hungary is a shitshow”, one Uber employee wrote, and the company withdrew from the Hungarian market

Uber’s vice president of marketing, Jill Hazelbaker, told the ICIJ that the company made a number of mistakes before 2017, but Uber has changed a lot since then and has a new leader. “We have not and will not make excuses for past behavior that is clearly not in line with our present values,” she wrote.

The leaked documents not only shed light on Uber’s history, but also provide an unprecedented deep and detailed insight into the opaque practice of lobbying in Hungary. For a few years before 2010, a lobbying law was in force, requiring lobbyists approaching government decision-makers to register and report on their activities, but very few of them did so. After its return to power in 2010, Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz party got rid of this law, and the obligation to report was abolished in principle. “Since the abolition of the lobbying law in 2010, there is no legislation in force that could ensure transparency in various policy-making processes,” Transparency International Hungary wrote in a 2014 report.

A promising start

Uber, which started in the United States and expanded to many countries around the world, was built on a very simple idea: its app connected passengers directly with drivers working for Uber by skipping taxi dispatch centers. Riders did not usually pay cash for the ride, but Uber would charge their credit card, keep its own commission, and then transfer the rest back to the driver. The driver and the passenger would then mutually rate each other, so that troublesome passengers and problematic drivers would be eliminated from the system. Uber, which expanded mainly in big cities, was typically cheaper than local taxi fares, so it quickly became popular with passengers – and incurred the wrath of taxi drivers everywhere.

In the Hungarian market in particular, the Budapest taxi decree had been passed less than a year before Uber’s arrival, which meant that taxis in the capital charged officially fixed prices. The taxi drivers’ associations, which were thus freed from price competition, had already predicted that Uber would operate illegally and that their aim was to “nip the service in the bud” in Budapest, as a taxi company boss put it.

Uber, on the other hand, communicated that it does not consider itself as a taxi service provider, but as a “community transport operator”. As Rob Khazzam, the company’s head of expansion in Central and Eastern Europe, put it in November 2014: “Uber is bringing innovation to a sector that has not seen real innovation for a long time. We’re not looking to replace an existing mode of transport, but to implement a new alternative in an environment that is not used to progress.” (When contacted, Khazzam said he did not wish to comment.)

According to the leaked documents, at the time, Uber was still prioritizing expansion in Eastern Europe, including Hungary. It hired international communications agency Grayling for lobbying in the region, so it was up to the company’s Budapest office to open doors with the Orbán government. Documents show that Grayling’s Budapest staff first raised the idea of approaching Dávid Vitézy, CEO of the Budapest Transport Center, and Gergely Böszörményi Nagy, head of Design Terminal, a government-financed organization, and a former staffer of minister Tibor Navracsics, who was often openly critical of Fidesz’s central decisions. “We have a direct connection to them”, wrote a Grayling employee about Design Terminal, which, at the time, was still a government-linked institution. (Böszörményi Nagy has now told Direkt36 that he has not been approached by anyone in the Uber case.)

At the same time, after only a few weeks, Uber thought that Grayling’s Budapest office had not lived up to expectations. Uber representatives sent them angry letters because they felt that certain tasks had not been carried out as agreed. They also complained that their political connections were inadequate. “Grayling have no connections to the party that runs the country; on the contrary, they are associated with the Liberal party, which is highly unpopular and marginalized. In today’s Hungary, that matters,” wrote Mark MacGann, one of Uber’s European managers.

MacGann did not elaborate on what he meant by this, but it is known that the head of Grayling’s Budapest office at the time was Gergely Ábrahám, who had been a spokesman for the Ministry of Transport between 2006 and 2008 when it was led by the liberal Free Democrats. (Grayling declined to answer our questions, claiming that “in accordance with our confidentiality agreement, we cannot disclose information about our clients to third parties.”)

Uber wasted no time. In November 2014, the day the service was launched in Budapest, they started working with a new lobbyist, Tamás Sárdi, a Hungarian representative of the international consultancy network FIPRA. “He can sometimes come across as a used-car salesman, but he has strong connections to the party in power at government and municipal level,” Mark MacGann wrote of him.

Sárdi did indeed have good government connections. This was shown by the fact that, at the time, he had a joint company with István Tiborcz, Viktor Orbán’s now billionaire businessman son-in-law and Zoltán Martonyi, son of former foreign minister János Martonyi, as well as Tibor Kuna, who was one of the government’s most important communications contractors at the time.

Sárdi’s first steps made a very good impression on Uber. While the leaked documents show that Grayling had not yet managed to set up a meeting with BKK CEO Vitézy, Sárdi succeeded in doing so in a matter of hours. As the lobbyist later wrote in an email, on the morning of 13 November 2014, he met with two Uber representatives who complained to him that they had been unable to get an in-person meeting with Vitézy. Sárdi then called Vitézy on the spot and arranged a meeting with him at 1:30pm that day, with the BKK CEO going to Sárdi’s office.

According to Sárdi’s subsequent email, Vitézy asked them to keep their meeting

“low profile in order he would not have all taxi companies at his doorstep but offered his help in finding a compromise with regard to the regulation at the municipal level later on.”

Vitézy acknowledged to Direkt36 that he had indeed met with Uber representatives. He added that it was his opinion already at the time that the “more flexible, digitalized operation offered by Uber’s app is good for passengers, but the taxi regulation has to be respected.”

On the day of the meeting with Vitézy, in the presence of Uber representatives, Sárdi also called the chief of staff of the development ministry, who, according to Sárdi’s email, “called me back within 10 minutes” and agreed to sit down to “talk through the next steps” on the upcoming taxi legislation.

The news was greeted with great optimism at Uber, and this mood continued for some time. They managed to arrange a meeting with a deputy state secretary for transport and then with a head of department from the Ministry of National Development. Promises were made that they would be shown the draft taxi law that was being prepared and that Uber would be formally invited to the consultations needed to prepare the law. Sárdi also indicated in November that he would be able to talk about the issue with two ministers who will be traveling with Orbán to South Korea in the same delegation as him. (We asked Sárdi several questions, but he declined to answer them, saying that “we have no right or means to report on our internal communications with our clients to third parties.”)

Taxi drivers showed their strength

However, the good news for Uber was followed by bad news in December, just weeks after the service launched in Budapest.

It started when István Tarlós, then mayor of Budapest, fired Dávid Vitézy, who was seen as an ally of Uber. The emails reveal that it was then mooted that Vitézy should be hired as a lobbyist, but there is no record indicating that he was actually approached about it. Vitézy himself told Direkt36 that “I have not lobbied for Uber, and no such request or approach has ever been made.”

Later, it also became increasingly clear that the government was not open to Uber’s ideas. Sárdi explained this to Uber by saying that the government wanted to avoid a major taxi strike at all costs.

This was not mentioned in the leaked correspondence, but the Orbán government was in a difficult political situation at the time. Just a few weeks earlier, massive demonstrations against a proposed internet tax forced the government to back down. The government was also shaken by the so-called visa ban scandal (the essence of which was that the US had imposed a travel ban on Hungarian state officials and people close to the government suspected of corruption).

Uber manager Rob Khazzam made clear in his December 5 assessment that there are “challenges ahead” in Budapest:

“So far there is little political will to support Uber, mainly for the usual reasons (taxis, conservatism), but also because of anti-American sentiment and geopolitical reasons. The draft we’ve seen is pretty tough and not favorable to Uber (no car-sharing, for example).”

And yet the government’s position was not initially clear. According to a leading player in the taxi industry, at the time, they perceived that policymakers didn’t really understand what the taxi industry had against Uber.

Taxi drivers had several concerns, many of which stemmed from the fact that Uber was operating without following the rules that apply to the taxi industry. Unlike drivers of traditional taxis, Uber drivers did not have the official license required to drive a taxi, the cars did not have to meet strict requirements (from their age to their yellow color to their equipment) and the app, rather than a standard taxi meter, tracked the journey and handled the payment. Fares were paid to a Dutch company, and Uber paid almost no tax on its revenues in Hungary – a recurring criticism of Uber from the government. The taxi drivers also complained that Uber worked with variable pricing instead of fixed prices and that the company had no functioning domestic customer service or dispatch center.

Taxi associations therefore lobbied hard. According to one taxi industry source, apart from being “lucky” and “in the right place at the right time”, what also worked in their favor was that they had been in constant contact with municipalities and the government for years. They were careful to talk regularly not only to senior officials but also to the heads of the relevant departments. “The only way forward is to maintain informal contacts,” said another source, who added that, for example, regular meetings at car shows, exhibitions, and similar events were of great importance. “It makes more difference than sending a six-page letter out of nowhere,” he added.

An event in March 2015 illustrated how entrenched the relationship between taxi drivers and the government was. Taxi organizations wrote a letter to Viktor Orbán and, according to two sources familiar with the events, it took them less than two days to receive a reply from Bence Tuzson (then Fidesz parliamentary group spokesman and state secretary for government communications), who Orbán had appointed for handling the issue. They met, and an hour later, at a joint press conference, Tuzson clearly stood up for taxi drivers and a regulation that applies to everyone. (The state secretary did not respond to our questions about Uber.)

Under these circumstances, Uber didn’t really have a shot, despite its growing popularity with passengers.

Uber was also at a disadvantage when Miklós Seszták, Minister of National Development, cancelled a planned meeting with Uber representatives in February 2015 and told Sárdi that it was politically risky for the government to support Uber. Seszták has now written to Direkt36 that he does not remember all his meetings after all this time. He did remember meeting Sardi, but claimed it was not in his capacity as a lobbyist (he did not specify in what capacity).

Minister Miklós Seszták would rather not meet Uber – Source: Direkt36

Shortly after the cancelled meeting, in early March, the Ministry of Development sent a letter to Sárdi formally informing him that they would not change the proposed taxi regulations in favor of Uber.

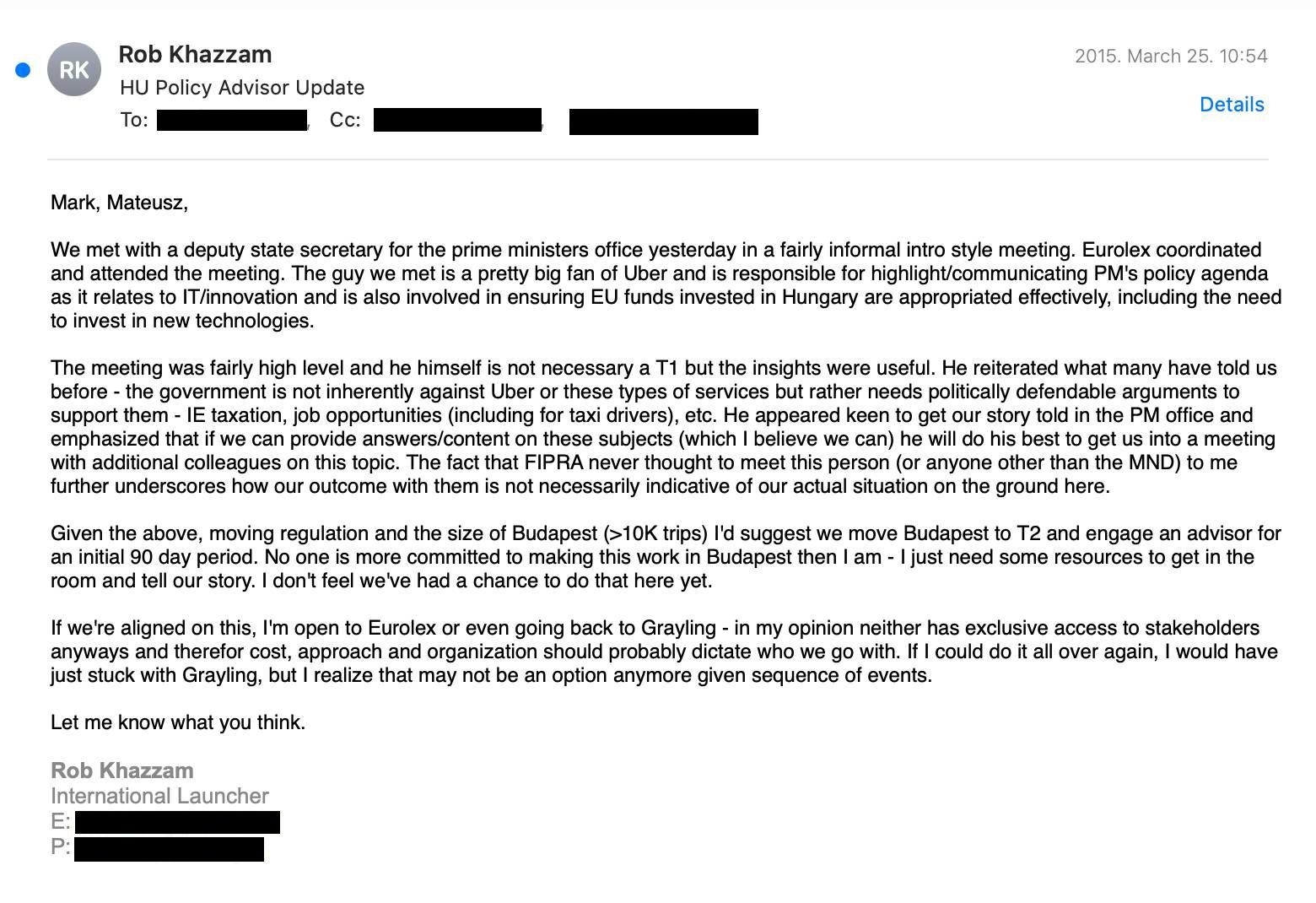

However, Uber has not given up. Having already been disappointed in Sárdi, they started working with a communications company called Eurolex, which organized a meeting for them at the Prime Minister’s Office, then headed by János Lázár. They met with one of minister Lázár’s closest associates, Deputy State Secretary Nándor Csepreghy, who was later described by an Uber executive as “quite a fan of Uber”. But Csepreghy also reiterated the government’s position, as others have said already, that the government is not necessarily against Uber, but can only support them if they can get politically defensible arguments about, for example, how much tax Uber pays in Hungary and how many jobs it creates. Csepreghy also pledged to keep the issue on the agenda within the Prime Minister’s Office and promised to help set up meetings with other relevant staff.

State secretary Nándor Csepreghy’s meeting with Uber – Source: Direkt36

Csepreghy, who is currently Lázár’s deputy minister in the Ministry of Construction and Investment, told Direkt36 that he met with Uber representatives in his office in a completely formal way. “I told them that they too have to comply with the same rules that other passenger transport companies have to comply with,” Csepreghy recalled, adding that he personally did indeed like to use Uber,

“but just because I personally like to drink a spritz (‘fröccs’) doesn’t mean that everyone in the government has to drink a spritz.”

According to a document, the Prime Minister’s Office was indeed seriously engaged in drafting the upcoming taxi regulation. According to an email from a senior Eurolex official, Nándor Csepreghy told them that at an executive meeting of the Prime Minister’s Office, held on 30 March and attended by all the ministry’s state and deputy state secretaries, they discussed whether to support the draft in its current form. The overwhelming majority was in favor of leaving it unchanged, but Lázár asked Csepreghy to prepare a discussion paper to be presented to the entire government.

Csepreghy told Direkt36 that this was the normal procedure in the ministry. “János Lázár always asked for a proposal before a decision, in which the different points of view are included,” he said.

At Eurolex, news of the discussion paper was welcomed. “This is a great achievement, as the draft will now be presented to the government as a discussion paper, which means that it will not only be decided on a yes or no vote, but will be thoroughly debated,” the Eurolex chief wrote. He added that this is a key moment, because if the legislation is not changed now, it will certainly be the legislation that will govern the sector in the next year or two.

One of the owners and managers of Eurolex, György Kertész, told Direkt36 that it is not customary in their industry to comment on clients, “but Uber left without paying, so we do not have a confidential client-agency relationship”. He added that they did organize some meetings for Uber, but “they did not bring any substantial progress” because Uber’s attitude to several issues was very rigid. “They thought that laws and rules only applied to others,” said Kertész.

Uber asked for help from someone other than Eurolex: they hired Imre Kónya, former Minister of Interior of the conservative government ruling Hungary in the early 90s, as an advisor, who met with the current minister, Sándor Pintér, and discussed the Uber issue. According to leaked documents, Kónya returned from the meeting with not very encouraging news. The former minister told Uber that the draft regulation – the content of which the company had so far tried unsuccessfully to influence – would be adopted within a few weeks, and that Uber, which had failed to comply with strict taxi rules, could even be threatened with a ban.

In June 2015, Kónya also organized a meeting for Uber representatives with János Lázár, but this did not bring a breakthrough for the company either. “János is very progressive and extremely powerful. He was very receptive at the meeting, but in the end the feedback was that other members of his party called off giving concessions to Uber because of the political risk of angering taxi drivers,” an Uber staffer wrote. (Kónya declined to comment to Direkt36 on his work for Uber, saying he was engaged in legal work, the details of which are covered by attorney-client privilege.

The new regulation was finally adopted in July 2015 and clearly stated that Uber is a taxi service provider, meaning that it is subject to the rules that apply to taxi drivers – from the technical requirements of the car to the driver’s qualifications to the operation of a mandatory dispatch service. Neither Uber’s drivers nor its cars were able to comply with the rules, and, from then on, Uber was even more regularly caught up in inspections by various Hungarian authorities.

Prepared for a raid

Uber has not only had a hard time lobbying but has also had a lot of trouble with the Hungarian Tax and Customs Authority (NAV). Several internal letters mention that the tax authority has been fining drivers working for Uber. For example, an email from September 2015 reveals that the tax authority fined five Uber drivers in a single week. NAV has launched a series of inspections of passenger transport operators. Inspectors have also been on the road to catch Uber drivers driving without the required qualifications and in cars that do not comply with taxi requirements. In the first half of 2016, Uber drivers were checked 350 times and almost HUF 3.7 million in fines were imposed, and 14 times the number plates were even removed from the cars of Uber drivers driving without a taxi license, NAV has told Direkt36.

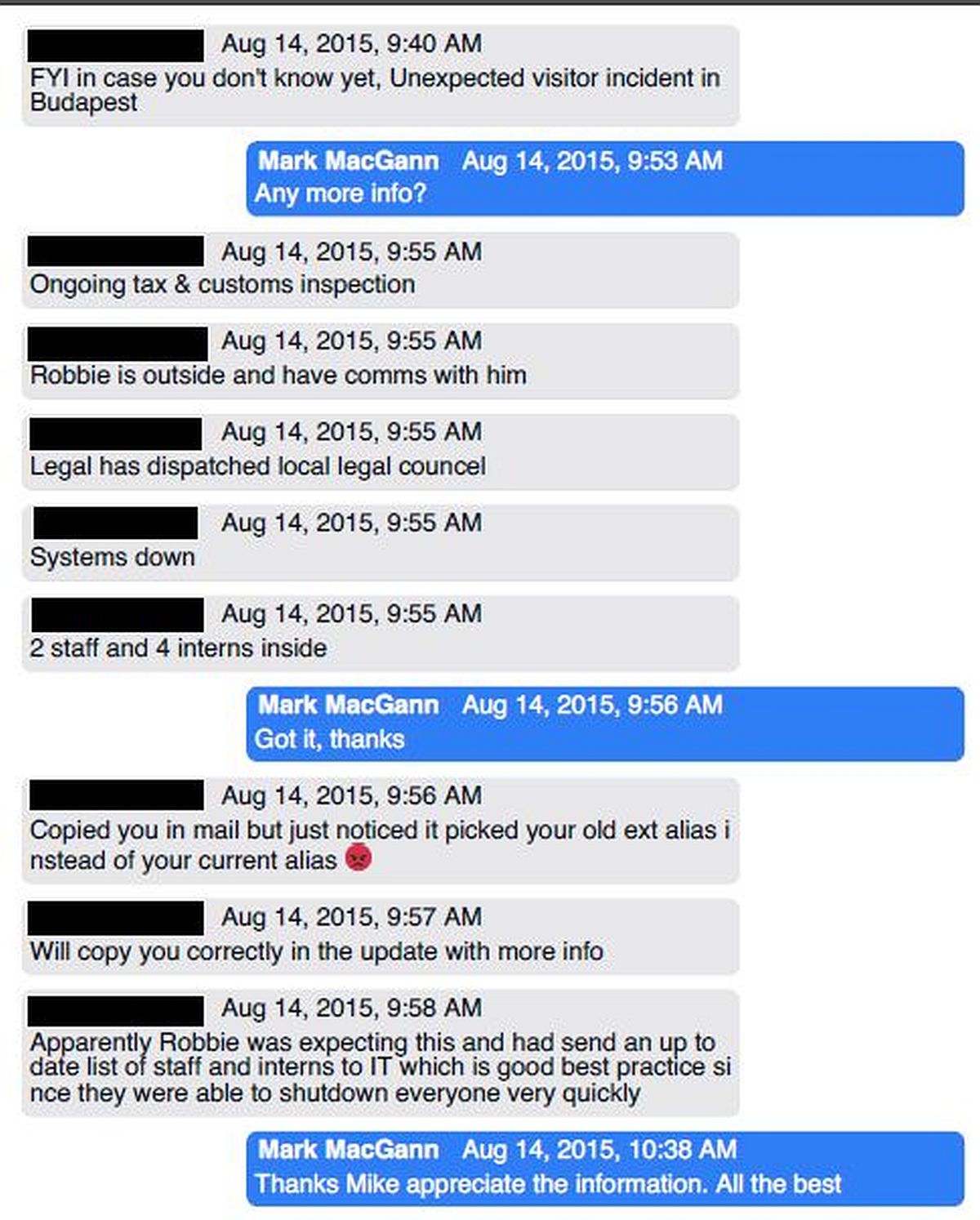

Uber’s Budapest headquarters were also raided by the authorities at least once. Although there is no public record of this and NAV refused to disclose any details citing tax confidentiality, it is clear from one of the messages exchanged that the incident occurred in late summer 2015 and that Uber used a special, secret method to obstruct the inspectors’ work. It was the so-called kill switch, which allowed Uber employees’ computers to be shut down remotely in a risky situation to prevent authorities from accessing documents. This was done at least a dozen times from Paris to Hong Kong, according to leaked internal emails.

On August 14, 2015, at 9:40 a.m., Uber’s regional head of security sent a message from his iPhone to Mark MacGann, one of Uber’s European managers, saying, “FYI, in case you don’t know yet, unexpected visitor incident in Budapest.” MacGann asked for more information. “Ongoing tax & customs inspection. Robbie is outside and have comms with him. Legal has dispatched local legal counsel,” he wrote. “Systems are down. Two staff and four interns inside,” he added later. “Got it, thanks,” MacGann replied.

“Unexpected visitor incident” in Budapest – Source: Direkt36

The regional head of security also told MacGann that “apparently Robbie was expecting this and had sent an up to date list of staff and interns to IT which is good best practice since they were able so shut down everyone very quickly.” Indeed, NAV’s investigation came as no surprise to Uber employees in Budapest, as revealed by an internal email that was written shortly before the raid. According to the email, NAV not only scrutinized Uber’s accounts, but also looked into their contractors and even “interrogated” Uber’s office staff. All this – according to the email – was done just to “create problems” for Uber.

Although he stressed that many details are unknown, László Hegedűs, a lawyer who specializes in economic criminal law, said that the Budapest case raises suspicions of abetment of crime. If a person “attempts to obstruct the criminal proceedings” against an other alleged perpetrator, they are aiding and abetting a crime, according to the Hungarian Penal Code. In this context, Uber managers who shut down computers or approved it, were not protecting themselves from the investigation but someone else, i.e. the company Uber. However, this only applies in case of criminal investigations. It is not clear from the documents what type of legal action was carried out against Uber and whether NAV carried out the raid in the context of a criminal investigation. The tax authority did not share any details, citing tax confidentiality, nor did it answer the question whether the disconnection of the computers was in breach of any law.

ICIJ has sent Uber a number of questions about the use of the “kill switch”. The company’s marketing manager responded that, since co-founder Travis Kalanick was ousted in 2017, they have not used a “kill switch” that could interfere with authorities’ investigations, and that they regularly cooperate with authorities who request information. Mark MacGann did not respond to a question about the events in Budapest but stated in general that in all cases where he has been involved in the use of the kill switch, it has been at the express instruction of Uber’s San Francisco headquarters. We also asked Rob Khazzam, who is presumably referred to as “Robbie” in the text messages, but he did not wish to comment.

Uber was also inspected by authorities when organizing its annual promotion campaign handing out ice cream. In one internal email, Uber employees complained that the Ministry of Health is “going to great lengths to investigate us and our ice cream vendor as a result of our UbeCream stunts. They inspected a partner and actually conducted a field report on the ice cream (!). Outcome still pending.” However, Direkt36 was unable to confirm the story, as an independent Ministry of Health did not exist in Hungary at the time and there is no public record of this incident. The Ministry of Interior, which is now responsible for healthcare in the country, did not respond to our question about the case either.

Under these circumstances, Uber carefully considered every move it made to avoid navigating into an even worse position with the government. This is shown by the exchange of letters in September 2015 regarding the refugee crisis that was then unfolding. At the time, thousands of refugees from Syria heading to Western Europe camped in Budapest train stations. Uber managers then discussed in a series of emails, how to react to the situation, and if they should take on the task of transporting refugees to the border. However, as the Fidesz government was beginning to take an anti-migrant stance and was under huge international pressure, the idea was dropped, in order not to “embarrass” the Hungarian government. They feared that it would come off as

“here is this illegal US company with no respect for local rules and regulations meddling in our problem with the immigrants”.

“Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria are a shitshow”

Despite the uncertain situation and Hungarian regulations treating Uber as an illegal taxi operator, the car-sharing app remained popular. By early 2016, there were 1,200 drivers and 80,000 passengers in Budapest. Taxi drivers felt their business was in decline, and as Uber continued to operate despite the rules, a group of taxi drivers went on strike for three days in early January 2016.

They blocked two major city roads, causing gigantic traffic jams and outrage among residents. Official taxi organizations did not support the protest, with the CEO of Főtaxi, Tibor Szunomár, for example, saying that the strikers had “done more harm to the taxi drivers and their profession in Budapest than Uber”. Instead, they wrote another letter to Viktor Orbán, asking the prime minister to “make it clear that Hungarian laws apply to everyone equally”.

The government has tried to calm the mood, with state secretary Bence Tuzson saying that he believed taxi drivers were right, and the PM saying the same in his usual radio interview on Friday. At the same time, the government asked protesters to stop the demonstration. On 22 January, Uber executives indicated in an email that they were not concerned by Orbán’s remarks:

“The local team is not worried, they expected such a stand because the government wants the protesters off the streets as soon as possible (…) At this moment we do not expect any more official action or bans”,

they assessed in an internal email. This was somewhat contradicted by the fact that, just the same day, the tax authority issued a statement saying that another wave of checks would follow and that any illegal taxi driver would be fined 200,000 HUF. The next day, an Uber driver was beaten up by six people in Budapest and taken to hospital. Some of the attackers were reported to be drunk taxi drivers.

Uber was considering what could be done. According to documents, an idea emerged that a letter should be written to Viktor Orban. But Mark MacGann said it wouldn’t make much sense. ” So I think this seems very knee jerk, and I haven’t seen the letter. (…) Once I see that and agree on it, I’d be more amenable to a letter to a PM who isn’t the type of man to be deeply moved by letters from US companies…”

They were left with few good ideas after the government made it clear after the strike that it intended to enforce the rules, and they still could not get close to Orbán. They were also thinking of launching a big public campaign to support Uber, which would involve winning over well-known people, but this was seen as a last resort because it could “put government in a corner”.

In an email in mid-February, discussing the situation in Eastern Europe, Marc MacGann wrote: “Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria are a shitshow.”

The fact that former liberal Minister of Economy János Kóka was willing to help Uber through his network of contacts could not change the situation. When Uber contacted him, Kóka sent a text message saying: “Let us discuss this. I love Uber and hate taxi drivers, happy to assist you in identifying the most useful inroads. Best, János.” Kóka’s potential employment was discussed in several emails, once describing him as “a big CEO, who was a Minister and leader of his party. Now has quit politics because he hates Orbán and he likes being a successful businessman 🙂 ” Kóka has now told Direkt36 that there was no follow-up to the initial contact. Although he agreed with Uber’s ambitions, he would not have had the means to help their cause anyway, he added. (As it has since emerged, Kóka has built good relations with certain government figures despite his liberal political background.)

Sespite its PR campaigns, the story of Uber in Hungary was coming to an end. In April 2016, Secretary of State of the Ministry of Development János Fónagy announced that a bill would be submitted to ban unlicensed, untaxed and illegally operating passenger transport services. The aim, as stated by Fónagy, was to force Uber to “stand in line”. In May, Uber organized a demonstration: Hussars rode on horses along Budapest, carrying a petition signed by 30,000 supports to the Ministry of National Development, but Minister Miklós Seszták did not receive them personally.

The promised amendment to the law was adopted in June 2016 and gave the National Transport Authority the right to ban Uber’s app. Uber did not wait for it to come into force: the company left the country by the end of the month. According to Zoltán Fekete, the managing director of the company’s Hungarian subsidiary, the tally was 1200 Uber drivers, 160,000 app users and millions of kilometres driven in Budapest.

The Ministry of National Development reacted that Uber would rather withdraw from Hungary “than operate legally, pay taxes and compete fairly with tax-paying Hungarian taxi drivers.”