It only took ten days for the Syrian dictator’s moneyman to get Hungarian residence permit

Atiya Khoury, the Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad’s moneyman bought Hungarian residency bond in 2014, which allows him to reside and to do business in Hungary and in the European Union. A joint investigation of 444 and Direkt36 revealed in March that Khoury participated in Hungary’s controversial residency bond program, which has been widely criticized for posing corruption and security risks. Hungary’s Immigration and Asylum Office confirmed Khoury’s involvement after the publication of our article.

The Immigration Office also said at the time that Khoury received a permanent residence permit in 2017, in spite of the fact that he had been on the U.S. Treasury Department sanction list since the summer of 2016. According to the sanction documents, Khoury owns and operates Moneta Transfer & Exchange, a financial services network that deals with currency exchange and cash transfers and has played an important role in maintaining Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s regime. Khoury is accused of moving cash between Syria, Lebanon, and Russia.

In July, Márta Demeter, a Hungarian MP of the green party LMP, filed a complaint with the prosecutor’s office because of the Hungarian residence permit of Atiya Khoury. She assumes that the Immigration Offices violates the law when it does not carry out further investigations and does not revoke Khoury’s residence permit.

Based on the complaint of the MP, the Prosecutor’s Office ordered an investigation because of suspicion of abuse of office, and the National Bureau of Investigation (NNI) launched an investigation on the 1st of August. However, the investigation was closed after two weeks, as NNI found no criminal offence. Demeter told Direkt36 that she would file a complaint with the Prosecutors Office against the decision of the NNI.

It only took ten days to receive the residence permit

The NNI resolution that closes to investigation reveals new details about how Khoury received Hungarian papers. NNI writes that Khoury is on the U.S. Treasury Department sanction list, his assets in the US were frozen and US companies and nationals were prohibited to do business with him. The documents quote the sanction documents that claim that Khoury financially helps the Syrian government, including the country’s central bank. The NNI claims, however, that Khoury does not appear on the sanctions list of any other countries and international organizations – including the European Union and the United Nations – and that US financial actions against him “do not mean an absolute ground for refusal to issue or revoke Hungarian residence permit.

What is more, even if they were considered as an absolute ground for refusal, the Immigration Office still would not break the law with now revoking his residence permit. According to the NNI, the law that regulated Hungary’s residency bond program forced the Immigration Office to revoke a residence permit only in certain cases. For example, if it turns out that the applicant has given false information or if he/she is banned from the country. The investigation into Khoury’s case found no signs of such conditions.

There are other cases, when the law did not oblige, but only authorized the Immigration Office to revoke a permit. For example, if „factors, which had been the basis of issuing the residence permit, significantly change to such an extent that they would represent an absolute ground for refusal”. According to the NNI, in Khoury’s case this category “could arise as according to the implied viewpoint of the plaintiff” his appearance on the sanction list is a “significant factor”. NNI adds, however, that “the choice of words of the law the Immigration Office has a discretionary power of judgment” in such cases, thus the Immigration Office does not violate the law if it does not revoke the permit.

We can only do this work if we have supporters.

Become a supporting member now!

According to information provided earlier by the Hungarian authorities, potential bond investors went through a strict security screening carried out by four authorities, but no further details were made public about the screenings. Two sources talked about the shortcomings of the security screenings, one of them suggesting that there could not have been any in-depth investigations because of the vast number of participants in Hungary’s residency bond program.

The NNI resolution that closes to investigation reveals that Khoury first applied for Hungarian residence permit on the 19th of December 2014, when he was not yet on the US sanction list. He received the residence permit in ten days, on the 29th of December, but the document does not include details about what type of security screening was carried out during those days.

Authorities found everything all right

Khoury applied for a permanent residence permit on the 23rd of September 2016., two months after he had been put on the sanctions list. This process took longer than the previous one. The Immigration Office asked three authorities to investigate whether Khoury poses a risk to Hungary’s national and public security:

– The Constitution Protection Office

– The Counter Terrorism Centre

– The Police Headquarters in Budapest.

The Immigration Office also checked in “relevant databases”, such as the Schengen Information System, whether there are any travel bans in force against Khoury.

Khoury also proved that he has a place to live in Hungary, his subsistence is ensured and has sufficient financial resources for healthcare services. He also attached a “certified translation of a certificate of clean criminal from his country of origin and of residence, which also certifies that he does not appear in Hungarian criminal records either,” the NNI wrote. As the authorities raised no objections during Khoury’s security screening, he received a permanent residence permit in Hungary on the 25th of May 2017.

Under the residency bond program between 2013 and 2017, foreigners could obtain permanent residence permit in Hungary in exchange for an investment of 300 thousand euros in special government bonds. Almost 20 thousand foreigners received Hungarian papers under the program. It was suspended in 2017 and terminated with a law modification in 2018.

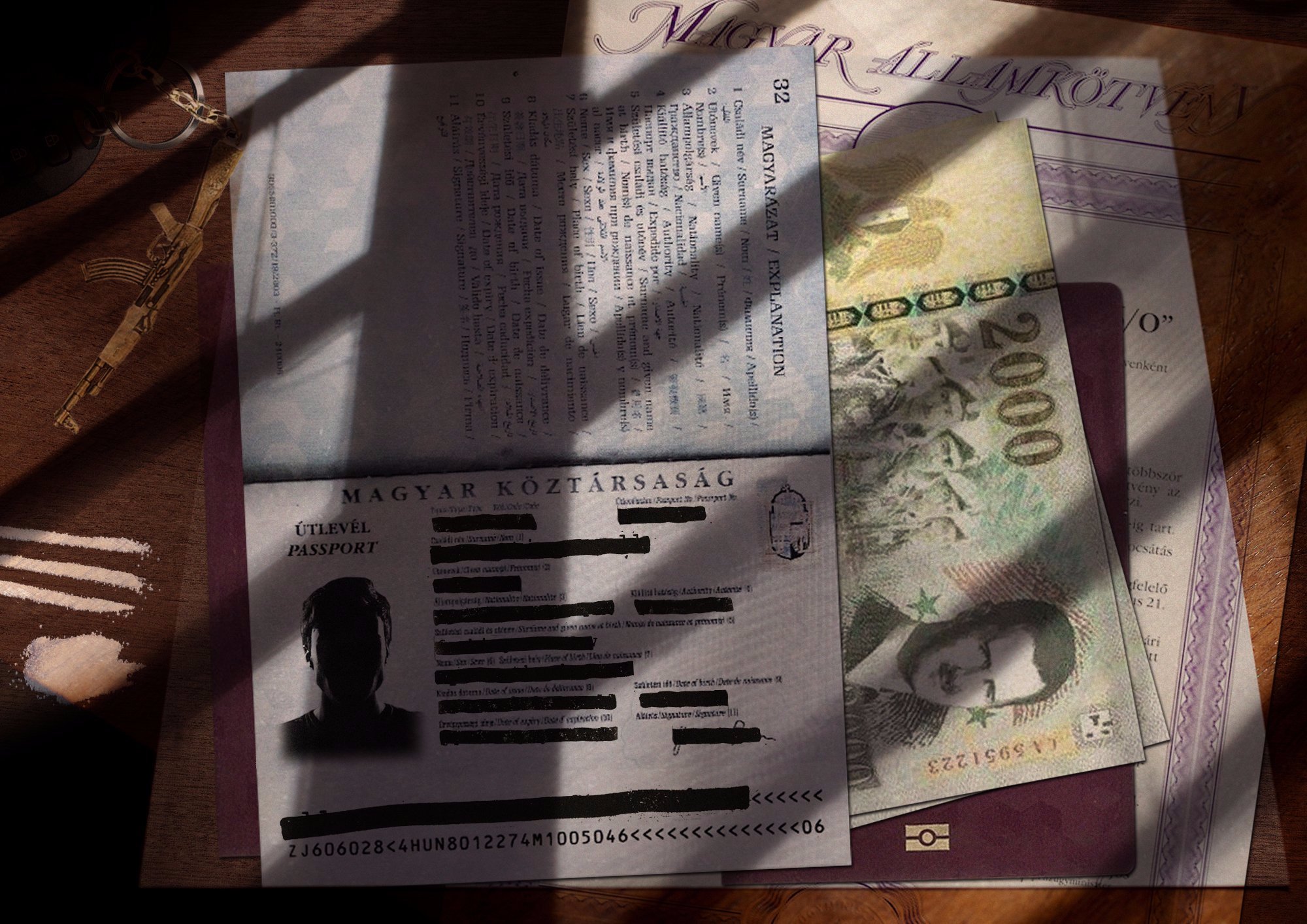

Cover photo: Bence Kiss, 444.hu

András Szabó contributed to this article.