We Investigated China’s Foreign Intimidation Operations. It Led Us to the Leader of a Hungary-based Organization

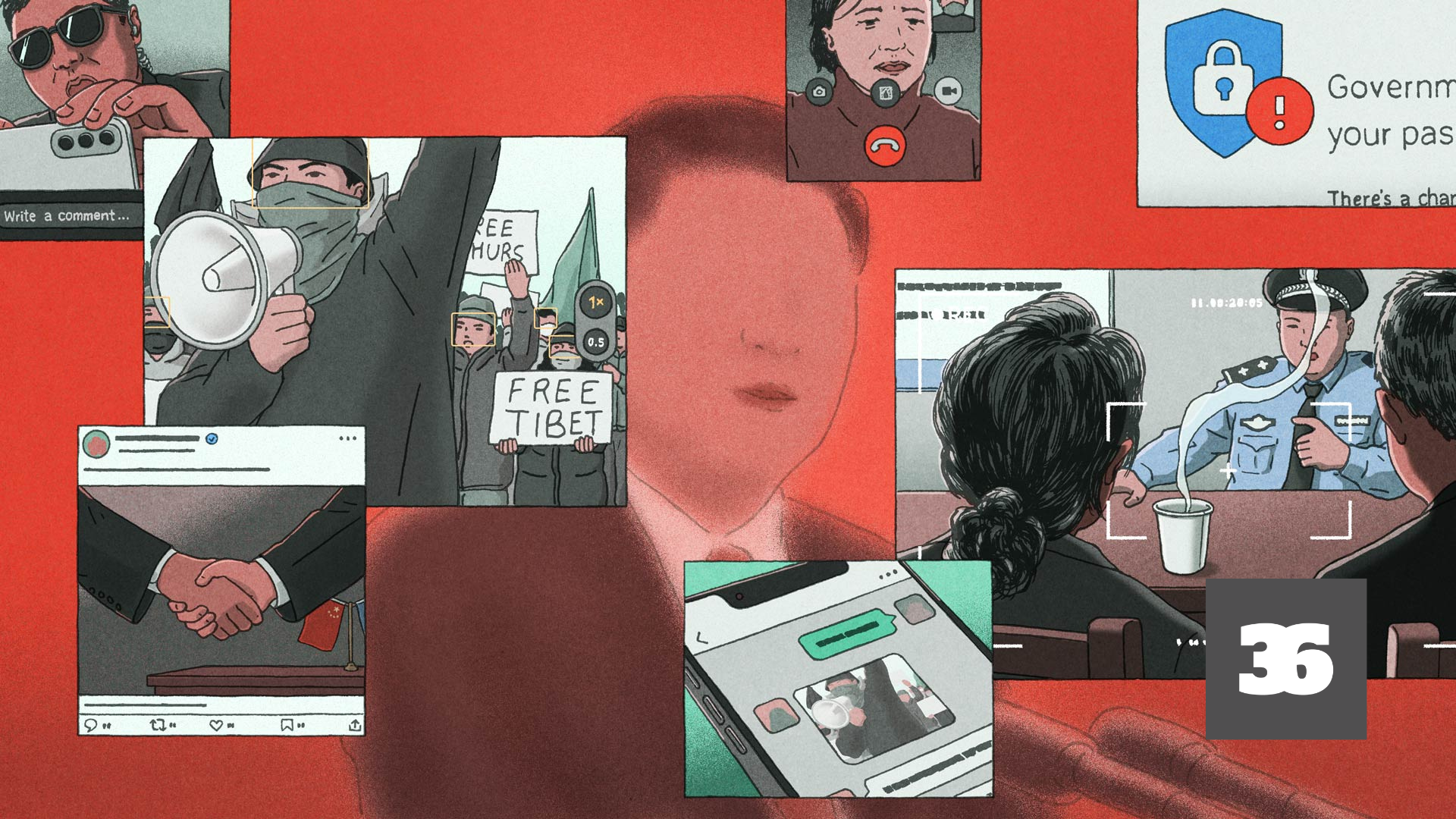

A tense situation unfolded at the United Nations Conference on Human Rights in February 2023. In the elegant Wilson Palace conference room in Geneva, UN representatives reviewed a report on China, which also addressed the oppression of the Uyghur and Tibetan minorities.

Sitting in the room was Thinlay Chukki, head of the Geneva Tibet Office and the Swiss representative of the Tibetan government-in-exile, established due to China’s occupation. After the presentation, a Chinese man—previously unknown to her—approached and asked to take a photo with her. She agreed, and a colleague read the name tag around the Chinese man’s neck: Ma Wenjun, President of the Chinese-European Cultural, Art, and Sports Association, registered in Budapest.

After the photo was taken, Ma continued taking pictures, this time turning his camera toward the Tibetan delegation and photographing them without their consent. The Tibetans tried to block Ma’s camera with a backpack and repeatedly asked him to stop, but he dodged the backpack and continued photographing them.

After a UN staff member intervened, Ma deleted the photos of the Tibetans. However, he did not cease what the Tibetans perceived as harassment. Later, he waited outside the building and again attempted to photograph Chukki and her colleagues as they left.

The incident was formally reported by staff from the Tibetan Centre for Justice, who were also present, to the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, which has opened an investigation into the matter. Correspondence regarding the complaint was also reviewed by Direkt36.

Ravina Shamdasani, a spokesperson for the UN Human Rights Office, told Direkt36 that the complaint was taken seriously. However, since UN staff intervened on the spot and had the images deleted, they considered that no further action was necessary for the time being. “Our team considered his behavior to be objectionable, and so took action on the spot. I wouldn’t say we ‘closed the file,’ as we would certainly examine any new information that could come to light,” Shamdasani wrote.

Ma Wenjun claims there was a misunderstanding at the conference in Switzerland. “I was excited to learn about this high-level meeting discussing minority rights in China,” Ma wrote to Direkt36, adding that he is a Muslim and therefore considers himself part of a Chinese minority as well. He said he arrived at the conference with an interpreter who helped him translate the presentations and discussions.

“I thought this was an open conference, so I asked the lady sitting next to me if we could take a photo together as a memento, and she initially agreed. I don’t understand why she suddenly became angry and refused to be photographed,”

Ma wrote, adding that he stopped taking photos of the Tibetans outside the building. “Perhaps there was a miscommunication through the interpreter,” he explained.

However, experts say this behavior is typical of China’s efforts to identify and suppress its critics.

According to a 2024 study by the Institute for European Global Studies at the University of Basel, politically active members of Tibetan communities worldwide are systematically monitored by individuals linked to the Chinese Communist Party. Their participation in political events and meetings is recorded. “The surveillance and photography itself is intimidating,” the study notes. According to the research, the footage is also used to identify individuals and exert pressure on their family members remaining in China.

Pál Nyíri, a professor at Corvinus University of Budapest, said that such conspicuous photography is more likely intended to intimidate rather than gather information. “If they wanted to spy, they wouldn’t do it with amateurs and in such a conspicuous way,” he told Direkt36.

The incident in Geneva was uncovered as part of an international investigative journalism project led by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ). The investigation, titled “China Targets,” involved 42 media outlets around the world, with Direkt36 as the only Hungarian partner. The ICIJ and its partners reviewed internal government documents, police records, and confidential UN and Interpol materials to uncover how the Chinese state attempts to intimidate critics abroad.

Liu Pengyu, a spokesperson for the Chinese Embassy in Washington, rejected the allegations of international intimidation. “These claims are groundless and fabricated by a handful of countries and organizations to slander China,” Liu said in a statement to the ICIJ. “There is no such thing as ‘reaching beyond borders’ to target so-called dissidents and overseas Chinese,” Liu stated.

Man of the United Front

Ma Wenjun is part of a global network run by China called the United Front, which we covered in detail in an article last year. The United Front is a unit of the Chinese Communist Party tasked with controlling key members of the overseas Chinese diaspora and suppressing voices critical of China, thereby expanding China’s influence. As part of these efforts, the United Front maintains contact with representatives and associations of the overseas Chinese diaspora worldwide. Direkt36 has identified 26 Chinese associations and 56 individuals linked to this network in Hungary, including Ma Wenjun and the Chinese-European Cultural, Art, and Sports Association he founded.

Ma, originally from Nanjing, said he moved to Hungary in 2013 through a residency bond program and currently owns a wholesale and retail company. Alongside his influential Chinese political connections, Ma, as president of his association, also appears alongside Hungarian government politicians. In 2017, his association helped organize the Hungarian Chinese Film Festival, which was attended by Hong Kong film star Jackie Chan, a known supporter of the Chinese Communist Party. Zoltán Balog, a former Hungarian minister, also gave a speech at the event. That same year, Ma shook hands with Foreign Minister Péter Szijjártó at an economic conference.

Minister of Foreign Affairs and Trade Péter Szijjártó and Ma Wenjun at the China and Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) Business Forum in November 2017 – Source: www.ourjiangsu.com

However, Ma said it was merely a one-time encounter.

“At the end of the meeting, when he passed by me, I asked for a photo with him. He was very approachable,”

Ma recalled. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade did not respond to Direkt36’s request for comment.

In 2017, Ma, along with four compatriots, was appointed as a “consular protection liaison officer” by China’s former ambassador to Budapest. According to the embassy’s statement, their role was to maintain contact with members of the Chinese diaspora and help “solve the problems of their compatriots in Hungary.” Asked by Direkt36, Ma said he caught the embassy’s attention after organizing free language courses for more than 2,000 Chinese residents in Hungary at his own expense. He said his appointment was necessary because the number of Chinese arriving in Hungary was growing and the embassy’s consular department was understaffed.

“This role is similar to that of an honorary consul, but since China doesn’t have honorary consul positions, it was termed Consular Protection Liaison Officer,” Ma explained to Direkt36. He said he assisted in matters such as arranging burials, finding lawyers for disputes, and connecting family members in China with their relatives in Hungary. “While the title sounds prestigious, the work was incredibly challenging,” he wrote, adding that he did not receive payment for it. His contract was terminated in 2020 after the embassy decided he no longer had the time and energy for the position.

The Chinese Embassy and the Hungarian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade did not respond to Direkt36’s inquiries about the appointment.

Ma also regularly participates in events organized by the United Front. In January, for example, he traveled to the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, where he listened in person to the annual speech by the Party Secretary of Jiangsu Province. “I am honored to have been invited to attend the meeting of the CPPCC. (…) I am not interested in politics, but I appreciate the recognition of my work by the Chinese government, the Hungarian government, and the UN,” he said.

In 2022, he also traveled to Nanjing to join other members of the Chinese diaspora in reviewing Chinese President Xi Jinping’s speech at the Central United Front Work Conference. Ma said he personally covers the costs of these trips.

Textbook Solutions

Journalists involved in the investigative project coordinated by the ICIJ interviewed more than 100 people worldwide who have been targets of Chinese state intimidation.

The ICIJ also examined confidential Chinese documents—a 2004 Chinese police textbook and a 2013 guideline for domestic security officers—that revealed the techniques used by Chinese authorities. These included digging up possible past offenses by the targets and harassing their Chinese relatives.

“The principle and general playbook hasn’t changed, but they are operating at a very different level today,”

Katja Drinhausen, a researcher at the Mercator Institute for Chinese Studies in Berlin, told the ICIJ.

The guidelines and the testimonies from interviewees closely matched.

Half of those interviewed who had been targeted by Chinese authorities reported that the harassment extended to family members living in China, who were regularly visited and interrogated by police or state security officials. Several victims also told the ICIJ that their relatives in China or Hong Kong were contacted by police shortly after the targeted individuals participated in protests or public events abroad.

Sixty interviewees reported being followed by Chinese officials or their agents, or being subjected to surveillance or espionage. Twenty-seven said they had been victims of online smear campaigns, and nineteen reported receiving suspicious messages or being targeted by hacking attacks, including those attributed to state agents. Some said their bank accounts were frozen in China and Hong Kong. Twenty-two interviewees reported receiving physical threats or being assaulted by civilian supporters of the Chinese Communist Party.

For each interview, journalists verified the information through documents, photographs, message exchanges, and official complaints presented by the interviewees.

The majority of the targets interviewed by the ICIJ and its partners said they had not reported these incidents to the authorities in the countries where they lived. Many cited fear of retaliation from China or a lack of confidence that local authorities could help. Those who did report their cases often said local police either did not take action or responded that they could do nothing without clear evidence of a crime.

“Only when they see my dead body will they act,” said Nuria Zyden, a Dublin-based Uyghur, referring to the police response after she reported being followed by three Chinese men.

Experts say repression against perceived enemies of the party-state has intensified since the start of Xi Jinping’s presidency in 2012. In internal statements, Xi has urged security officials to stay vigilant against “Western anti-China forces,” including dissidents.

“Xi is committed to deepening Communist Party control over China and the diaspora,” said Emile Dirks, who researches authoritarianism at the University of Toronto’s Citizen Lab. “No opposition to this goal, however small or weak, is tolerated.”

The Son of a State Security Officer

Among the targets interviewed by the ICIJ was Jiang Shengda, a Chinese artist and activist living in Paris.

Jiang, 31, grew up in an influential family in China. His father worked as a state security officer, and his ancestors included other high-ranking government officials. Jiang attended elite schools in Beijing alongside the children of powerful figures.

At 18, Jiang briefly joined the Chinese Democracy Party, a U.S.-based political group advocating for constitutional democracy in China. This decision had serious consequences: he was arrested and accused of attempting to subvert state power.

Jiang said he was shocked to learn that police had compiled a thick dossier on him, including private letters and even comments from one of his primary school teachers. He was detained for three nights and had his passport revoked for about a year. Jiang said his father was reassigned from his role as a foreign intelligence officer to a position at a state-owned company.

In 2018, Jiang moved to France, confident that he would be free to express his views there. He became involved in several actions protesting human rights abuses in China, which quickly attracted the attention of Chinese authorities.

As his activism grew bolder, hackers attacked his art website dozens of times, and Google warned him that “government-backed intruders” were attempting to steal his passwords.

The pressure intensified ahead of Chinese President Xi Jinping’s visit to Paris in May 2024.

Jiang told the ICIJ that a few days before Xi’s arrival, his parents called him to report that plainclothes secret police had been visiting them for months. It was clear these visits aimed to pressure Jiang into remaining silent during Xi’s trip.

However, Jiang was undeterred. He participated in a demonstration at Place de la République in Paris, addressing a crowd of protesters from Tibet and Hong Kong.

“They [the Chinese police] have demanded that we keep quiet during Xi Jinping’s visit to France. … Such threats are part of transnational repression … that is just an extension of [China’s] tyranny,” he said.

Shortly after his speech, Jiang called his parents. He learned that, while he was preparing to go on stage, police had called his parents’ home and demanded a midnight meeting. They warned: “Your kid used to do certain things overseas that are against Chinese laws. We could turn a blind eye to it. But this time the big leader comes [to France]. If he does something embarrassing for the big leader, it’d be difficult for us to handle.”

Jiang told the ICIJ that Chinese authorities have used the same tactics against the families of other members of the activist group he leads. As a result, some have abandoned activism and left the group.

“Even if we live in a free country, we are still afraid to speak up and suffer harassment from the party,” Jiang told the ICIJ.

Joey Qi helped us to accurately translate the answers we received from MaWenjun.

Sylvain Besson, a journalist from Tamedia in Switzerland, contributed to this article.

This article is based in part on an ICIJ article. The full version is available here. Scilla Alecci led the writing of the ICIJ’s article.

Illustration by ICIJ