Orbán öt éve harcol az EU-val. Legszűkebb köre addig gazdagodott belőle

Van azonban egyvalami, amiről a miniszterelnök nem szokott beszélni. Arról, hogy 2010-es kormányra kerülése óta több, hozzá egykor és jelenleg is személyesen kötődő ember cégei jelentős részben olyan beruházásoknak köszönhették a látványos fellendülésüket, amelyeket nagyrészt vagy teljes egészében a nyugati adófizetők pénzéből felduzzasztott európai uniós költségvetés finanszírozott.

Ilyen üzletember a miniszterelnökkel ezekben a hetekben nagy zajjal háborúzó, de egészen a közelmúltig szoros politikai szövetségesének számító Simicska Lajos. Ilyen vállalkozó Mészáros Lőrinc felcsúti polgármester, aki az Orbán szívügyének számító felcsúti fociakadémiát működtető alapítvány elnöke és Simicskához hasonlóan gyerekkora óta ismeri a miniszterelnököt. Ebbe a körbe tartozik továbbá az Orbán-család egyik új tagja, a miniszterelnök legidősebb lányának férje, Tiborcz István is.

Dokumentumok mélyén

Az már eddig is ismert volt, hogy ezeknek az embereknek a vállalkozásai az elmúlt öt évben feltűnően jól szerepeltek az állami beruházásokra kiírt pályázatokon, és ennek köszönhették látványos növekedésüket. Mivel Magyarországon a fejlesztések jelentős része uniós forrásból valósul meg, ezért azt is lehetett tudni, hogy a cégek biztosan jutottak EU-s pénzhez. Ennek mértékét azonban nehezen lehetett meghatározni, mert ha követni akarjuk az uniós pénzek magyarországi útját, akkor ahhoz egymástól független állami adatbázisok dokumentumainak mélyén megbúvó információkat kell összegyűjteni és rendszerezni.

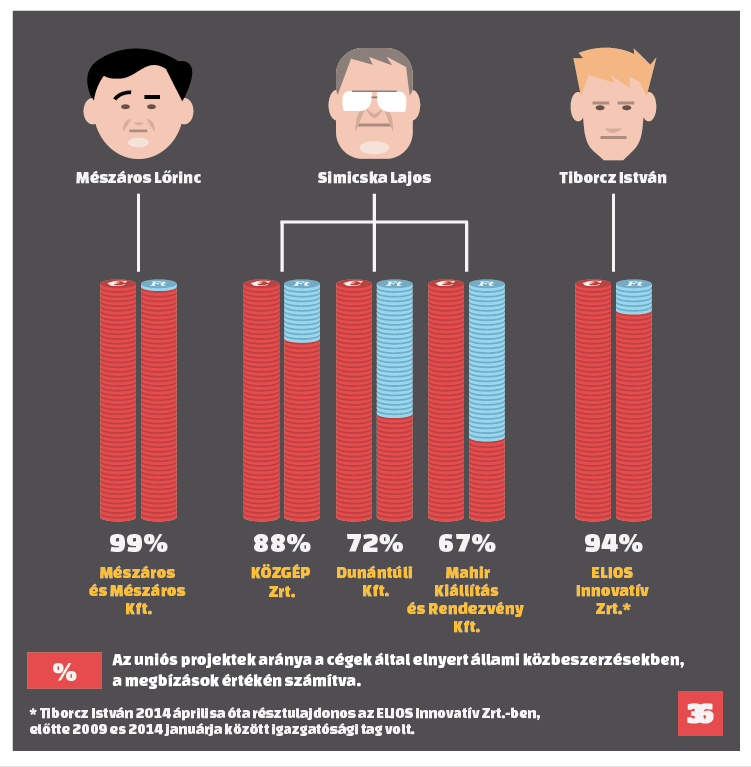

Az Orbánhoz kötődő embereknek a cégei által elnyert közel 300 állami megbízás dokumentumait feldolgozva világosan kiderült, hogy mindegyik cég, illetve cégcsoport kifejezetten komoly kedvezményezettje az EU-s költségvetésnek.

A Simicska Lajos érdekeltségébe tartozó cégek által elnyert közbeszerzések több százmilliárd forintra rúgó összértékének közel 88 százalékát EU-s projektek adják. Bár ez a szám nem feltétlenül tükrözi azt, hogy a cég bevételének pontosan mekkora aránya származik az EU-tól, jelzi azt, hogy a tevékenységének milyen óriási részét képezik az uniós finanszírozású projektek. Még nagyobb ez az arány Tiborcz István és Mészáros Lőrinc összességében szintén sokmilliárdnyi megbízást begyűjtött cégeinél. A Tiborcz résztulajdonában álló energetikai cégnek, az Elios Innovatív Zrt.-nek a közbeszerzések összértékét tekintve több mint 94 százalékban uniós projektjei vannak, a felcsúti polgármester építőipari vállalkozásánál, a Mészáros és Mészáros Kft.-nél pedig ez az arány több mint 99 százalék.

Az elemzésből – amelyhez a hivatalos állami adatbázisok mellett a K-Monitor antikorrupciós szervezet, valamint a CEU-n működő Microdata és a Corruption Research Center Budapest nevű kutató csoportok adatait használtuk – az is kiderült, hogy ezeknek az EU-s finanszírozású projekteknek közel negyedét úgy nyerték el ezek a cégek, hogy a pályázaton nem volt versenytársuk. Ez nagyjából megfelel a közbeszerzéseken általában tapasztalható aránynak, a CRCB-től kapott adatok szerint ugyanis 2010 és 2014 között 26 és 32 százalék körül mozgott azoknak a pályázatoknak az aránya, amelyeken csak egy ajánlattevő volt. Az Elios Innovatív azonban kilóg a sorból. Ennek a cégnek az elmúlt egy évben – amikor már a miniszterelnök veje is tulajdonos lett – az elnyert EU-s projektek több mint felénél nem kellett senkivel sem megküzdenie a munkáért.

Kinek a pénze?

Az elnyert pályázatok között vannak több tízmilliárdos építési beruházások, néhány százmillió forintos energetikai fejlesztések és pármilliós kommunikációs megbízások is. Ezeknek a beruházásoknak állandó kellékük, hogy a megvalósításuk helyszínén plakátok hirdetik azt, hogy a pénzt az Európai Unió adta. Ha azonban szigorúan vesszük, akkor ezeken a táblákon az is állhatna, hogy a miniszterelnök által gyakran kritizált nyugati országok adófizetői állták a számlát.

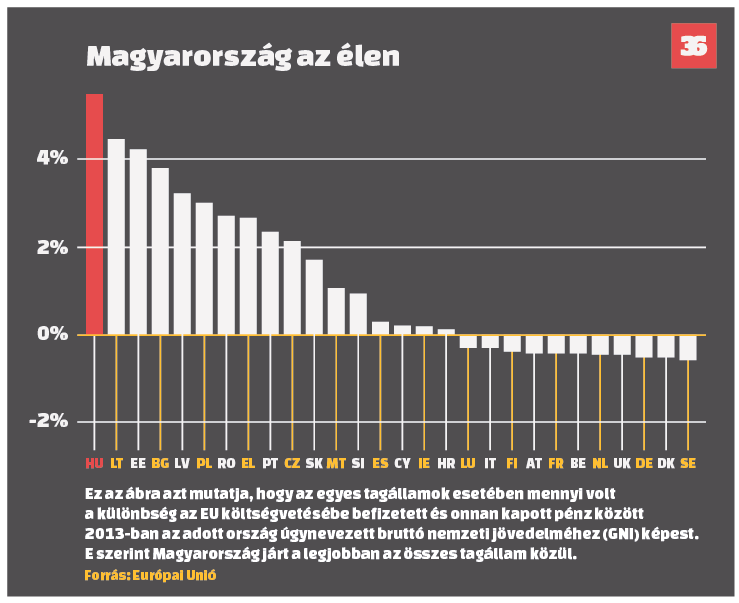

Az Európai Unió költségvetése ugyanis úgy néz ki, hogy minden ország belead valamennyi pénzt a közös kasszába, de vannak, akik kevesebbet, míg mások többet kapnak vissza belőle. Jellemzően a fejlett nyugati és északi államok – élükön Németországgal, Svédországgal és Dániával – tartoznak az első, az elmaradottabb kelet-európai államok pedig a második kategóriába. A cél ezzel az egyenetlen elosztással az, hogy a szegényebb országok felzárkózzanak a fejlett nyugathoz.

“Az Európai Unió fejlesztéspolitikájának egyik deklarált célja a felzárkóztatás. Már a római szerződés óta fontos eleme az európai közösségnek a szolidaritás, természetesen a gazdasági és egyéb integráció mellett, azokat kiegészítve” – mondta Kálmán Judit, a Magyar Tudományos Akadémia Közgazdaságtudományi Intézetének uniós fejlesztésekkel foglalkozó kutatója, utalva az EU történetében mérföldkőnek számító 1957-es szerződésre.

Magyarország ennek a rendszernek az egyik legnagyobb haszonélvezője volt az elmúlt években a felzárkóztatást célzó úgynevezett Strukturális Alapok egyik kedvezményezettjeként. “Az előző, 2007-től 2013-ig tartó ciklusban az egy főre vetített Strukturális Alap-támogatásokat tekintve mi kaptuk a második legtöbbet” – mondta Kálmán, hozzátéve, hogy ugyan a most induló új időszakban csökkent a számunkra elérhető összeg, de még mindig az élmezőnyben, a negyedik helyen áll Magyarország, ha lakosságarányosan nézzük a hozzáférhető támogatásokat.

Forrás: Direkt36 gyűjtés, Németh Gyula

A kutató megjegyezte azonban azt is, hogy a nyugati államok is nyernek ezen a rendszeren. Egyrészt a fejlesztéspolitikai célok egy része (fenntartható növekedés, biztonság, társadalmi kohézió) az egész EU érdekét szolgálja. Másrészt a nyugati tagállamok cégei piacot szereznek, illetve a szegényebb tagállamokban működő leányvállalataik – mint például nálunk az Audi – ugyanúgy hozzáférnek az uniós forrásokhoz, mint a helyi cégek. “Így vannak azért csatornák, ahol ennek a pénznek egy része visszamegy nyugatra” – mondta Kálmán.

A teljes kép tehát árnyalt, a miniszterelnökkel személyes viszonyt ápoló három ember cégeinél viszont egyszerű volt a képlet. Cégeik teljesítménye látványosan javult párhuzamosan azzal, ahogy egyre több és több – túlnyomórészt uniós forrásból finanszírozott – közbeszerzést nyertek el az elmúlt szűk öt évben.

A Simicska-birodalom zászlóshajójának számító Közgép ugyan már 2010 előtt is komoly szereplőnek számított az építőiparban, de azóta másfélszeresére növelte éves bevételét, 2012-ben és 2013-ban is 60 milliárd forint körüli szintet produkálva. Mészáros Lőrinc építőipari cége, a Mészáros és Mészáros 2010-ben még csak 853 millió forint bevételt termelt, 2013-ban viszont már több mint 9,7 milliárdot. Az Elios Innovatív Zrt. pedig eleve csak 2009-ben alakult, és néhány év alatt vált többmilliárdos forgalmat bonyolító céggé.

Ebben a növekedésben minden jel szerint meghatározó szerepet játszottak az állami megbízások. Bár egyik cég sem válaszolt a kérdéseinkre – amelyek között szerepelt, hogy a közpénzből fizetett beruházások mekkora részét képezik a bevételüknek -, honlapján a Közgép és az Elios Innovatív is szinte csak állami munkákat tüntet fel referenciaként (a Mészáros és Mészáros Kft.-hez nem találtunk weboldalt). Az Elios referenciái között van ugyan néhány piaci munka is, de nem világos, hogy ezeket közvetlenül a cég végezte-e el. Többhöz ugyanis zárójelben oda van írva, hogy “üzletágvezetőnk személyes referenciája”.

A pénz útja

Azt a nyilvános adatbázisok legmélyebb elemzésével sem lehet megmondani, hogy a cégek pontosan mennyi uniós pénzt kaptak eddig. Az elnyert közbeszerzések egy része még le sem zárult, így a cégek még nem feltétlenül jutottak pénzhez. Ha pedig pusztán a cégek által szerzett uniós finanszírozású közbeszerzések értékét nézzük, akkor egy erősen torzító számot kapunk.

A cégek ugyanis a megbízásoknak egy jelentős részét konzorcium tagjaként – tehát más vállalatokkal közösen – nyerték el, az pedig nem derül ki a pályázati dokumentumokból, hogy egymás között hogyan osztják el a pénzt. A Közgép például a 2010 óta elnyert közel 80 EU-s projektjéből mindössze tízet csinál egyedül. Így hiába halmozott fel a cég mintegy 650 milliárd forintnyi értékű, EU-projektekkel kapcsolatos szerződést 2010 óta (és még 10 milliárdnyi szerződést a Közgép által tulajdonolt Dunántúli Távközlés Kft. és a szintén Simicska érdekeltségéhez tartozó Mahir Kiállítás és Rendezvény Kft.), ennek valószínűleg csak egy részét fogja megkapni.

Az is nehezíti a számolást, hogy sok EU-projekt vegyes finanszírozású, tehát az uniós pénz mellé a magyar állam is odatesz valamennyit. Ezek az arányszámok beruházásonként változnak, és a 100 százalékos uniós vállalás mellett vannak olyanok is, amelyeknek az EU még a felét sem fizeti ki.

Ilyen szórás tapasztalható Simicska, Mészáros és Tiborcz cégei esetében is, bár a Direkt36 elemzése azt mutatta, hogy az általuk elnyert megbízásoknál azért nagyrészt az EU állta a számlát. Az adatbázisok hiányosságai miatt a projektek egyharmadánál nem lehetett fellelni az arányszámot, de a többi esetében majdnem minden harmadik beruházásra 100 százalékban az EU-ból jön a pénz, és a maradéknál is túlnyomórészt 75 százalék feletti arányokat találtunk. Ez azt jelenti, hogy a cégeknek kifizetett pénz nagy része jó eséllyel az EU költségvetéséből érkezik.

Tiborcz és a 100 százalék

A három különböző érdekeltség közül a miniszterelnök veje által résztulajdonolt, 2010 óta több mint 6 milliárd forintnyi EU-projekttel összefüggő szerződést begyűjtő Elios Innovatívnál követhető leginkább a pénz útja. Ezt a céget korábban E-OS Innovatív Zrt-nek hívták, és többségi tulajdonosa sokáig a Közgép volt. Simicska érdekeltsége azonban 2013 nyarán kiszállt belőle, és a cég ekkor vette fel az Elios Innovatív nevet. Tiborcz István már ebben az időszakban is tagja volt a cég igazgatóságának, tavaly áprilisban pedig egy cégén keresztül résztulajdont szerzett az Eliosban. Nagyjából erre az időre tehető a vállalkozás újbóli fellendülésének kezdete is.

2012-ben és 2013-ban összesen csak négy közbeszerzést nyertek el, a tavalyi év elejétől azonban egymás után szerezték a zömében EU-finanszírozású állami megbízásokat. A cég ezeket egyedül – tehát nem konzorciumban – nyerte el, az uniós finanszírozás pedig a megbízások közel felénél 100, a többinél pedig 85 százalékos.

Erre az időszakra esett az is, amikor az Elios elkezdte úgy elnyerni az EU-s megbízásokat, hogy a pályázaton senki más nem indult rajta kívül. A 2014 elejétől elnyert 16 pályázat közül kilencet kaptak meg így. Ezeknek a szerződéseknek az összértéke meghaladja a 3,5 milliárd forintot.

Legutóbb idén januárban Zalaegerszegen nyerték el így a közvilágítás fejlesztésére kiírt 850 milliós pályázatot. A zalaegerszegi polgármesteri hivatal azt közölte, hogy nem volt más választásuk, mint kihirdetni az egyedüliként pályázó Eliost győztesnek. “Mivel az egy ajánlat érvényes volt, az eljárást eredményessé kellett nyilvánítani a jelenlegi jogszabályok alapján” – írta a polgármesteri hivatal kommunikációs referense. Az Elios nem válaszolt a kérdéseinkre.

A gyakori konzorciumi tagság miatt az elmúlt öt évben közel 40 milliárdos EU-kötődésű szerződésállományt felhalomozó Mészáros és Mészáros Kft. és a Közgép esetében sokkal kevésbé követhető az, hogy mennyi pénz juthat el hozzájuk az EU költségvetéséből.

Egy, a Közgép pénzügyeit ismerő forrás szerint a cég tényleges bevételének nagyjából kétharmada származhatott EU-s pénzből az elmúlt öt évben (a pénzügyi adatok 2013-ig hozzáférhetőek, ezekből az derül ki, hogy a cégnek 2010 és 2013 között 221 milliárd forint bevétele volt). Ez a kétharmados arányszám arra a pénzre vonatkozik, amely már befolyt a Közgéphez. Nem szerepelnek benne a még folyamatban lévő, de már elnyert projektek, közölte a forrás, aki névtelenséget kért arra hivatkozva, hogy nincs felhatalmazása, hogy a Közgép belső ügyeiről nyilatkozzon. Maga a cég nem válaszolt a kérdéseinkre, és nem bocsátott a rendelkezésünkre olyan adatokat, amelyekkel ezt a nem hivatalos arányszámot le lehetett volna ellenőrizni.

Az új családtag

A Miniszterelnökség nem válaszolt az arra vonatkozó kérdéseinkre, hogy Orbán Viktor tud-e arról, hogy a hozzá személyesen kötődő emberek cégei haszonélvezői az uniós fejlesztési programoknak.

Tiborcz István esetében biztos bőven lett volna rá alkalma, hogy beszélgessenek erről. A most 28 éves fiatalember 2013 szeptemberben házasodott össze a miniszterelnök legidősebb lányával, Ráhellel. Orbán az esküvő előtt a Blikknek azt mondta, hogy “Istvánnal talán öt éve találkoztam először, a szüleit viszont már korábbról ismerem, édesapja orvos, jól működő gazdaságuk van”. Azóta készültek közös fotók is róluk, például akkor, amikor együtt pálinkáztak 2013 karácsonyán a fiatal házaspár otthonában.

Tiborcz már fiatalon ráállt az üzleti pályára. 23 évesen részt vett az Elios Innovatív elődjének alapításában, később pedig érdekeltsége lett tanácsadással, valamint ingatlanfejlesztéssel foglalkozó cégekben is. Az egyik legfrissebb szerzeménye az, hogy – mint arról elsőként az Átlátszó beszámolt – egy általa résztulajdonolt cég megvette a keszthelyi kikötőt üzemeltető vállalkozást.

Tiborcz kerüli a nyilvánosságot, de a feleségének egy közelmúltbeli megjegyzése azt sugallta, hogy jó körülmények között élnek. “Férjemmel önálló családunk van, saját lábunkon állunk, saját erőnkből boldogulunk, saját életünket éljük” – írta egy tavaly decemberi Facebook-bejegyzésben Orbán Ráhel, így reagálva arra, hogy többen elkezdték firtatni, miből telik neki arra a svájci magániskolára, ahol a tandíj több mint 58 ezer frankba (mostani árfolyamon mintegy 16,5 millió forintba) kerül.

A felcsúti barát

Mészáros Lőrinc és Orbán Viktor gyerekkora óta ismeri egymást: egy általános iskolába jártak Felcsúton, ahol mindenki ismert mindenkit. A miniszterelnök maga is utalt a közös gyökerekre, amikor tavaly februárban személyesen avatta fel a felcsúti faluházat. Felidézte, hogy a Mészáros család annyira erősen kommunistaellenes volt, hogy az egész iskolában az ő gyerekeik voltak az egyetlenek, akik kimaradtak az úttörő mozgalomból. “Még úttörő nyakkendőt sem tudtak a nyakába kötni Lőrincnek” – jegyezte meg Orbán.

Egykori iskolatársaik ugyanakkor azt mondták, hogy az iskolai években még nem volt köztük szoros kapcsolat. Mészáros három évvel fiatalabb Orbánnál, és ez gyerekkorban még nagy korkülönbségnek számít. Felnőttként a futball volt az, ami összehozta őket. Mészáros Lőrinc gázszerelő vállalkozóként támogatta a helyi futballcsapatot, amelyben a 90-es évek végén Orbán igazolt játékos volt. Később aztán Mészáros lett a kuratóriumi elnöke a felcsúti Puskás Ferenc Labdarúgó Akadémiát működtető alapítványnak, amelynek stadionját Orbán felcsúti háza mellett építették fel.

Orbán Viktor mögött jobbra Mészáros Lőrinc – Forrás: Orbán Viktor Facebook

Mészáros helyi szinten már 2010 előtt is jól menő vállalkozónak számított, de az elmúlt öt évben már országosan is jegyzett üzletemberré vált. Ebben kulcsszerepet játszott a több EU-finanszírozású állami projektet elnyerő építőipari cége, a Mészáros és Mészáros Kft., amely közvetlenül is kapott uniós támogatást. A cég 2011-ben és 2012-ben két pályázatot is nyert összesen közel 92 millió forint értékben a vállalkozás “technológiai”, illetve “innovatív” fejlesztésére. Mészáros aktív a mezőgazdaságban is, amelyen keresztül szintén jutott uniós pénzhez. Földjei után családja, illetve cégei több mint 390 millió forintnyi uniós támogatást vettek fel 2010 óta.

Üzleti sikereinek látványos külső jelei is vannak. Egyre jobb autókkal jár, és helyiek szerint 2013-ban költözött be abba a Felcsút határában álló impozáns házba, amely egy biztonsági kamerás kerítéssel körbevett hatalmas – az ingatlannyilvántartás szerint 37 ezer négyzetméteres – telek közepén terül el.

Talán az élet megoldja

Bár most attól hangos a sajtó, hogy milyen durva kirohanásokat intézett Simicska Lajos Orbán Viktor ellen, a miniszterelnököt minden jel szerint sokkal mélyebb és hosszabb viszony fűzte hozzá, mint akár Mészároshoz, akár Tiborczhoz. Simicska és Orbán barátsága a középiskoláig nyúlik vissza, és a kettejük szövetsége alapozta meg a Fidesz felemelkedését is. Orbán dolgozott a politika frontvonalában, Simicska pedig biztosította ehhez a stabil hátteret az üzletben és a médiában.

Simicska már az ellenzéki években is építette ezt a hátországot, de a gazdasági birodalma igazán a 2010-14-es kormányzati ciklus alatt teljesedett ki. Bár a Közgép térnyerésére kapta a legtöbb figyelmet, sok állami megrendeléshez jutottak hirdetési és kommunikációs cégei is. Ezeknek a megbízásoknak egy részét is EU-s források finanszírozták, és emellett Simicska résztulajdonában álló mezőgazdasági cégek közel 6,9 milliárd forint értékben részesültek az EU-s földtámogatásokból is.

Orbán és Simicska sokáig megbonthatatlannak tűnő kapcsolata mostanra látványosan megromlott. Ennek az első jelei azok voltak, hogy az elmúlt egy évben több olyan ember veszítette el kormányzati pozícióját, aki kötődött Simicskához. A kormány több olyan javaslattal is előállt, amelyek sértették az üzletember gazdasági érdekeit. Orbán Viktor egy tavaly decemberi interjúban már utalt arra, hogy van kettejük között konfliktus, de egy kérdésre válaszolva hozzátette azt is, a barátságukat “az élet majd megoldja”. Simicska azóta nyilvánvalóvá tette, hogy ez nem mostanában fog megtörténni. “Orbán egy geci” – mondta február elején több interjúban, de egy őt ismerő forrás szerint magánbeszélgetésekben már hónapokkal ezelőtt is keményen kritizálta a miniszterelnököt.

Közben azért a közvetett munkakapcsolat nem szakadt meg köztük teljesen. A Simicska érdekeltségei közé tartozó Mahir Kiállítás és Rendezvény Szervező Kft. nemrég, december közepén nyert el egy félmilliárd forintos keretösszegű szerződést Orbán Viktor hivatalától, a Miniszterelnökségtől. A cég feladata épp az, hogy közreműködjön a Miniszterelnökség által felügyelt európai uniós támogatási projektek kommunikációjában.

A cégekről szóló információkhoz az Opten és a Céginfo szolgáltatását hasznátuk.